My Journey

I let my best friend down when her sister Jenny died suddenly in 1987. At age 25, her brain aneurism was unexpected and devastating to her parents and three siblings, including my longtime friend Becky. I was only 18 at the time, just finishing my first year of college. I dealt with not knowing what to do in that moment by telling myself that it was best to “give her space”. We didn’t talk for almost a full year after that—the longest period I’ve ever gone without being in touch. Traveling with her in the summer of 1988, she was able to tell me one evening how abandoned and angry she had felt towards me during that time.

So, when my friend Mel’s father died in 1994, her step-mother leaving Mel only his collection of neckties, I knew exactly what to do: I offered to make her something with the ties. As we talked about what to do—the design, the colors, what she’d do with the finished piece—our relationship deepened, and Mel was able to transform a part of her grief into something beautiful and tangible, a quilt to hang in her home. It could remind her not just of her father, Ronnie, but in so doing, remind her of her own capacity to persevere, overcome, and to make the most of unexpected personal loss.

That was my first memorial quilt. I was finishing a three-year stint as a textile designer at Nike Apparel, following my education at The Oregon College of Art and Craft (with a degree in Fibers) and the Fashion Institute of Technology (with a degree in Textile Design for Industry). Working in manufacturing design taught me many useful skills, but also weighed heavily on my inspiration: I began to doubt my own creative abilities in the commercial context, and I struggled to capture current trends in my designs.

I became increasingly dissatisfied with the impersonal nature of corporate life; I felt disconnected working exclusively with computers and the layers of corporate approvals standing between me and the materials that brought me to textile design.

My mother was a silversmith turned photographer, my maternal grandmother a ceramicist turned metal sculptor, and my great-grandmother a needle arts marvel. My great-grandfather was an architect and my grandfather an engineer. I knew all of them except my great-grand-father, and everyone but my mother had emigrated from Austria to the United States during World War II.

They all taught me bits of their own craft, how to turn a creative idea into a tangible form, and how to balance a creative life with family life. In hindsight, it’s easy for me to see how these skills and observations melded into my current textile/quilt work —structural forms that involve math and ordered repetition combined with a sense of beauty that reflect the rich relationships like the ones woven through my Austrian ancestry.

When my beloved grandmother, the sculptor, died, I made a series of memorial quilts from her clothing and felt firsthand the comfort they afforded from that difficult loss. I also discovered how integral the stories and images I had of her were to how I approached each design. Each garment evoked memories—stitching them together into a single textile was transformational.

I knew then that I had touched on a pathway where I could employ my creative vision and intuition to meaningfully connect with, and serve, others. It took me more than two challenging decades of soul-searching to land with this clarity of purpose. Now there is no turning back. Memorial quilts honor relationship, they transform grief, they’re about trust, and they celebrate the human spirit, morphing challenge into beauty.

I have focused on memorial quilts almost exclusively for well over a decade. Establishing relationships with clients, learning about people alive and gone, and appreciating the contours of how my clients express their grief is the inspiration for the work.

“I have placed there a little door opening on to the mysterious. I have made stories.” —ODILON REDON

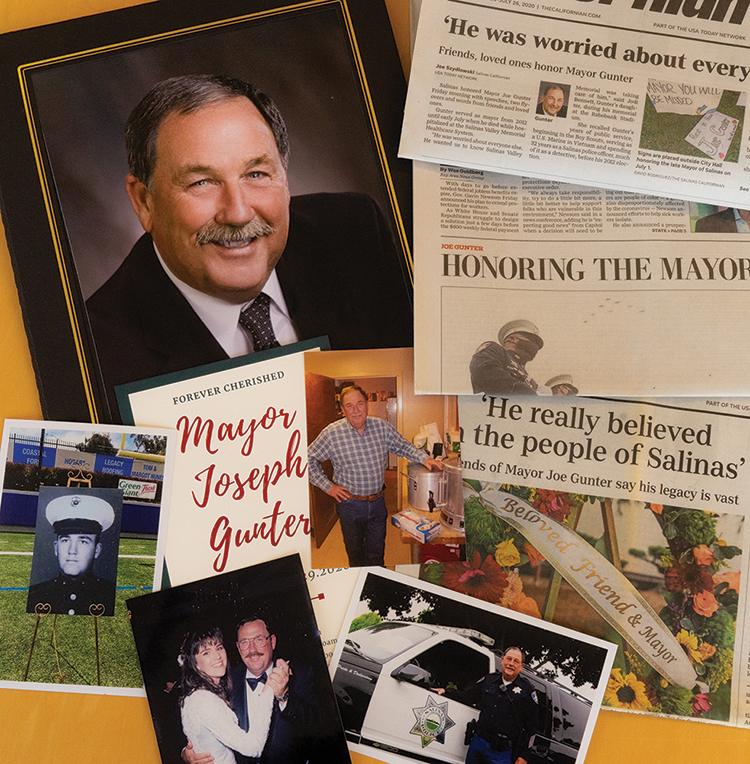

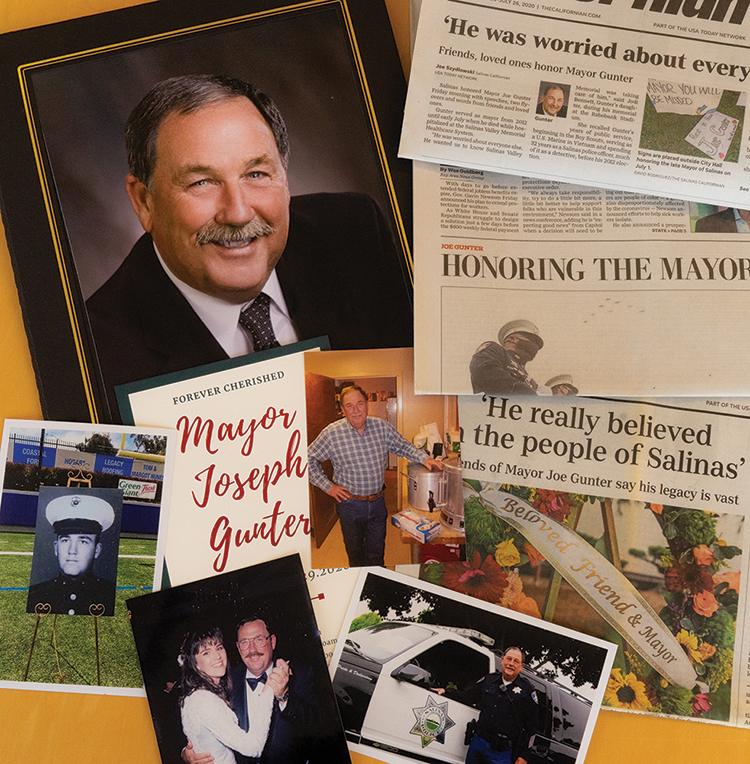

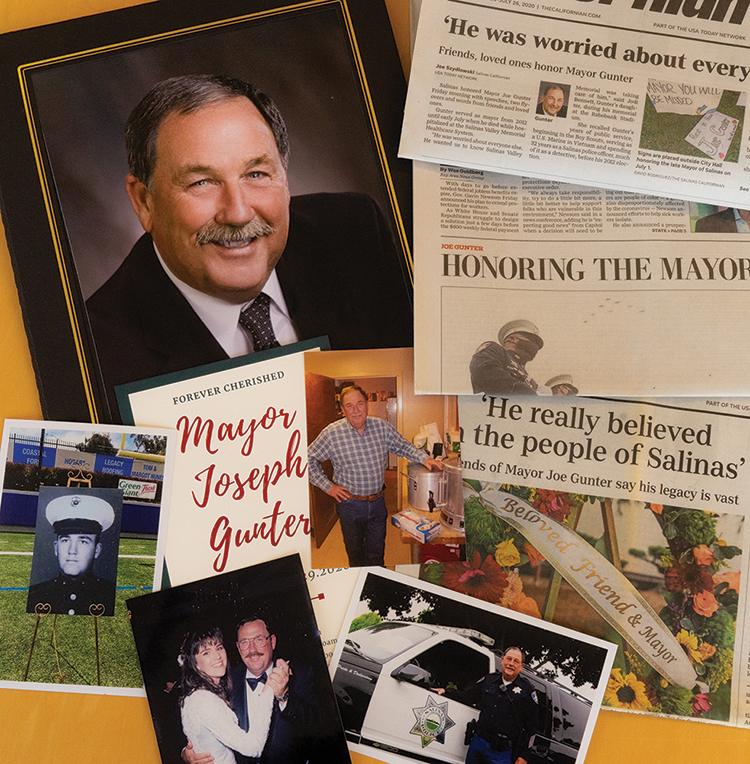

Joe Gunter, the Man Honored in the Quilt

Joseph Gunter (1947-2020) was the former mayor of Salinas, California, a whirlwind of a human being, a man who only knew how to be in service to his community. In addition to serving as mayor, he was also a veteran Marine who served in Vietnam, a 40-year police veteran, and he volunteered for the local women’s crisis line, the local air show, and the rodeo.

Joe’s daughter Jodi reached out to me amidst the pandemic quarantine to commission a series of quilts for herself and her two sons. Jodi’s deep connection to her father amplified the blow she felt from his sudden death. The batch of clothes she sent included blazers fit for a politician, rodeo security uniforms, and some lovely neckties. I set out to make quilts that embodied this admirable man’s legacy, as well as his daughter’s vision and aspirations.

My Process

Establishing trust is paramount, especially with clients turning over keepsake material. I begin each project with a phone call. The telephone exchange gives someone a chance to share their grief and memories of the person they lost.

I like to learn about their loved one’s personal interests, life passions, hobbies, even a favorite color. We discuss whether my client is looking for a functional quilt versus a wall-piece, an established quilt pattern or a custom design. Once they ship their loved one’s garments, I lay everything neatly on my table and turn my focus to design.

Before each session in my studio, I take a moment to light a candle and sit quietly for a few breaths in order to let the energy of the day settle. I think of the deceased by name and silently set intentions for my work. This brief ritual brings focus and expands my intuitive awareness.

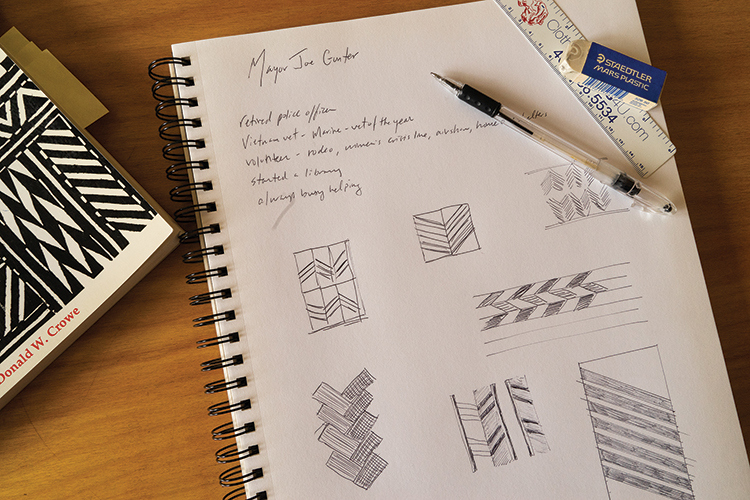

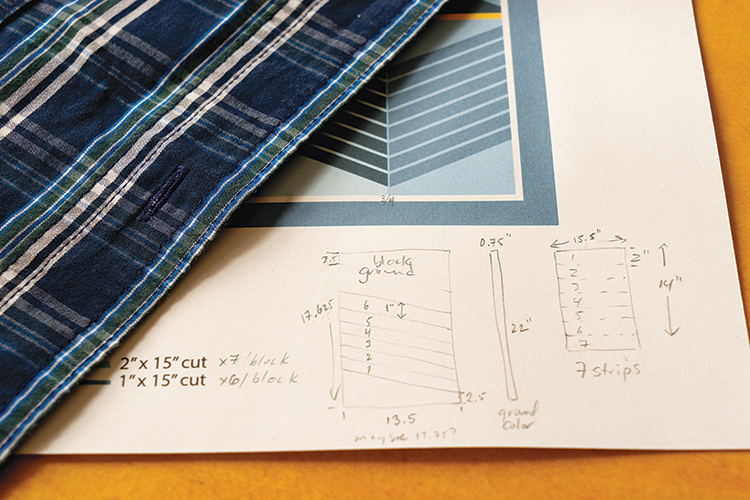

I begin all of my design ideas with pen and paper— sketching allows me to think freely. When I feel like I’ve created enough options, I begin building out each idea on the computer. These schematics help me to see how each pattern would look across a quilt as a whole; it also facilitates sampling different color allocations. With finite amounts of any one fabric—a single blue-striped shirt, say—precision in building schematics is critical.

Upon selecting a design, I begin garment deconstruction. I am careful to garner as much useable fabric as possible from each garment, especially if I have allocated it to a proportionally larger area of the quilt. Cutting out the individual pattern pieces is always exciting because this is the point where the individual garments transform into blocks of color and pattern, becoming my palette. Laying pieces out on my table is the moment where different fabrics can begin to interact in a way they never could as clothing.

I partner with a machine quilter to maximize what I do best. Machine quilting is an art form in and of itself, and with the emotionally sensitive nature of my work, I am fortunate to have found someone I trust deeply. I value the care and craftsmanship that Nancy Stovall of Just Quilting brings to each project. I liken the quilting pattern of a quilt to the bass line of a musical composition—it is rarely the first element that you hear, but it is integral to the harmony of the piece. Quilting can add a beautiful counterpoint to the pieced composition. After the quilting is completed, I sew on the binding, carefully wrap up the quilt, and send it to my client.

Establishing the sewing order is a bit like a chess move. Efficiency and careful planning rule the day. Sewing the final seam on the quilt top, spreading it out on my table, and admiring the full view is a cherished reward.

The moment of opening the box with the completed quilt is the defining moment of success for me—the moment when the client feels empowered by their very grief, the moment when they allow themselves to feel joy as an expression of grief. Working long-distance with people, I am not often present for the unveiling, but I always love to hear about it. I was elated when Leslie, one of a family of seven sisters from just outside Boston, called me after opening the box containing two quilts in remembrance of her husband, Al—“My sister and I opened the box, and we were just in tears—it’s just bringing him to life.” That is the ultimate success for me. Experiencing grief honestly, we benefit from its many gifts.

I will never be able to turn back the clock to visit with my dear friend Becky immediately following her sister’s sudden death. But with Jenny and Becky’s inspiration, I can continue to share others’ grief and to transform their hopes and dreams, through the textiles in my care, into works of art that serve as reminders that we can create beautiful things when we come together in a spirit of honesty and generation.

“If we do not honor our past, we lose our future. If we destroy our roots, we cannot grow.” — Friedensreich Hundertwasser

My Journey

I let my best friend down when her sister Jenny died suddenly in 1987. At age 25, her brain aneurism was unexpected and devastating to her parents and three siblings, including my longtime friend Becky. I was only 18 at the time, just finishing my first year of college. I dealt with not knowing what to do in that moment by telling myself that it was best to “give her space”. We didn’t talk for almost a full year after that—the longest period I’ve ever gone without being in touch. Traveling with her in the summer of 1988, she was able to tell me one evening how abandoned and angry she had felt towards me during that time.

So, when my friend Mel’s father died in 1994, her step-mother leaving Mel only his collection of neckties, I knew exactly what to do: I offered to make her something with the ties. As we talked about what to do—the design, the colors, what she’d do with the finished piece—our relationship deepened, and Mel was able to transform a part of her grief into something beautiful and tangible, a quilt to hang in her home. It could remind her not just of her father, Ronnie, but in so doing, remind her of her own capacity to persevere, overcome, and to make the most of unexpected personal loss.

That was my first memorial quilt. I was finishing a three-year stint as a textile designer at Nike Apparel, following my education at The Oregon College of Art and Craft (with a degree in Fibers) and the Fashion Institute of Technology (with a degree in Textile Design for Industry). Working in manufacturing design taught me many useful skills, but also weighed heavily on my inspiration: I began to doubt my own creative abilities in the commercial context, and I struggled to capture current trends in my designs.

I became increasingly dissatisfied with the impersonal nature of corporate life; I felt disconnected working exclusively with computers and the layers of corporate approvals standing between me and the materials that brought me to textile design.

My mother was a silversmith turned photographer, my maternal grandmother a ceramicist turned metal sculptor, and my great-grandmother a needle arts marvel. My great-grandfather was an architect and my grandfather an engineer. I knew all of them except my great-grand-father, and everyone but my mother had emigrated from Austria to the United States during World War II.

They all taught me bits of their own craft, how to turn a creative idea into a tangible form, and how to balance a creative life with family life. In hindsight, it’s easy for me to see how these skills and observations melded into my current textile/quilt work —structural forms that involve math and ordered repetition combined with a sense of beauty that reflect the rich relationships like the ones woven through my Austrian ancestry.

When my beloved grandmother, the sculptor, died, I made a series of memorial quilts from her clothing and felt firsthand the comfort they afforded from that difficult loss. I also discovered how integral the stories and images I had of her were to how I approached each design. Each garment evoked memories—stitching them together into a single textile was transformational.

I knew then that I had touched on a pathway where I could employ my creative vision and intuition to meaningfully connect with, and serve, others. It took me more than two challenging decades of soul-searching to land with this clarity of purpose. Now there is no turning back. Memorial quilts honor relationship, they transform grief, they’re about trust, and they celebrate the human spirit, morphing challenge into beauty.

I have focused on memorial quilts almost exclusively for well over a decade. Establishing relationships with clients, learning about people alive and gone, and appreciating the contours of how my clients express their grief is the inspiration for the work.

“I have placed there a little door opening on to the mysterious. I have made stories.” —ODILON REDON

Joe Gunter, the Man Honored in the Quilt

Joseph Gunter (1947-2020) was the former mayor of Salinas, California, a whirlwind of a human being, a man who only knew how to be in service to his community. In addition to serving as mayor, he was also a veteran Marine who served in Vietnam, a 40-year police veteran, and he volunteered for the local women’s crisis line, the local air show, and the rodeo.

Joe’s daughter Jodi reached out to me amidst the pandemic quarantine to commission a series of quilts for herself and her two sons. Jodi’s deep connection to her father amplified the blow she felt from his sudden death. The batch of clothes she sent included blazers fit for a politician, rodeo security uniforms, and some lovely neckties. I set out to make quilts that embodied this admirable man’s legacy, as well as his daughter’s vision and aspirations.

My Process

Establishing trust is paramount, especially with clients turning over keepsake material. I begin each project with a phone call. The telephone exchange gives someone a chance to share their grief and memories of the person they lost.

I like to learn about their loved one’s personal interests, life passions, hobbies, even a favorite color. We discuss whether my client is looking for a functional quilt versus a wall-piece, an established quilt pattern or a custom design. Once they ship their loved one’s garments, I lay everything neatly on my table and turn my focus to design.

Before each session in my studio, I take a moment to light a candle and sit quietly for a few breaths in order to let the energy of the day settle. I think of the deceased by name and silently set intentions for my work. This brief ritual brings focus and expands my intuitive awareness.

I begin all of my design ideas with pen and paper— sketching allows me to think freely. When I feel like I’ve created enough options, I begin building out each idea on the computer. These schematics help me to see how each pattern would look across a quilt as a whole; it also facilitates sampling different color allocations. With finite amounts of any one fabric—a single blue-striped shirt, say—precision in building schematics is critical.

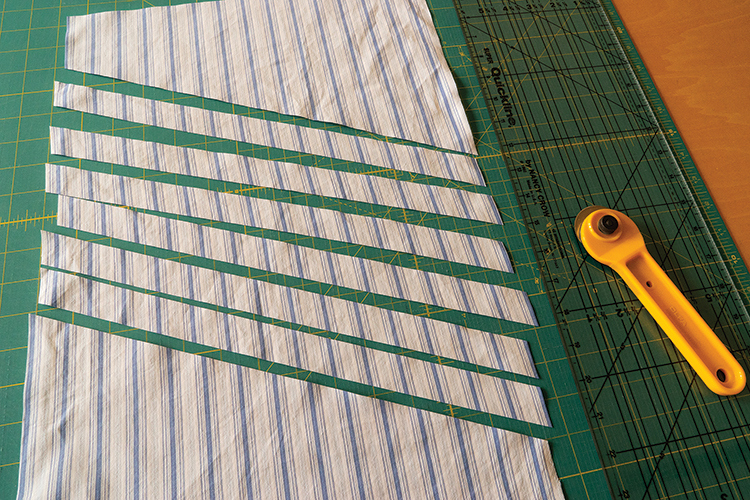

Upon selecting a design, I begin garment deconstruction. I am careful to garner as much useable fabric as possible from each garment, especially if I have allocated it to a proportionally larger area of the quilt. Cutting out the individual pattern pieces is always exciting because this is the point where the individual garments transform into blocks of color and pattern, becoming my palette. Laying pieces out on my table is the moment where different fabrics can begin to interact in a way they never could as clothing.

I partner with a machine quilter to maximize what I do best. Machine quilting is an art form in and of itself, and with the emotionally sensitive nature of my work, I am fortunate to have found someone I trust deeply. I value the care and craftsmanship that Nancy Stovall of Just Quilting brings to each project. I liken the quilting pattern of a quilt to the bass line of a musical composition—it is rarely the first element that you hear, but it is integral to the harmony of the piece. Quilting can add a beautiful counterpoint to the pieced composition. After the quilting is completed, I sew on the binding, carefully wrap up the quilt, and send it to my client.

Establishing the sewing order is a bit like a chess move. Efficiency and careful planning rule the day. Sewing the final seam on the quilt top, spreading it out on my table, and admiring the full view is a cherished reward.

The moment of opening the box with the completed quilt is the defining moment of success for me—the moment when the client feels empowered by their very grief, the moment when they allow themselves to feel joy as an expression of grief. Working long-distance with people, I am not often present for the unveiling, but I always love to hear about it. I was elated when Leslie, one of a family of seven sisters from just outside Boston, called me after opening the box containing two quilts in remembrance of her husband, Al—“My sister and I opened the box, and we were just in tears—it’s just bringing him to life.” That is the ultimate success for me. Experiencing grief honestly, we benefit from its many gifts.

I will never be able to turn back the clock to visit with my dear friend Becky immediately following her sister’s sudden death. But with Jenny and Becky’s inspiration, I can continue to share others’ grief and to transform their hopes and dreams, through the textiles in my care, into works of art that serve as reminders that we can create beautiful things when we come together in a spirit of honesty and generation.

“If we do not honor our past, we lose our future. If we destroy our roots, we cannot grow.” — Friedensreich Hundertwasser