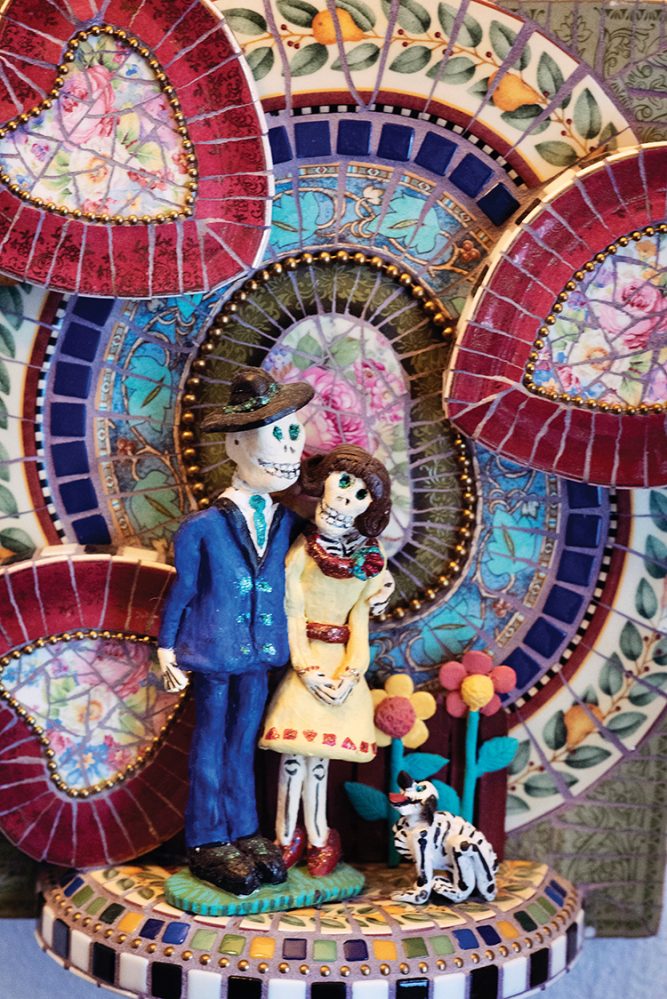

My inspiration comes from Mexican folk art and design.

The beautiful organic curves, scrolled shapes and vibrant colors replicating sunrises and sunsets make me want to capture them in a mosaic.

I’ve been collecting Mexican folk art ever since I was a child. This started when my uncle, who was living in Mexico, brought back Mexican art whenever he returned for a visit. Gradually, I refined my taste to collect primarily Day of the Dead-themed art.

The process for making mosaic altars begins by searching through my inventory of porcelain plates to find a palette of colors and texture that fits in with my idea of the mosaic I want to create.

My ideas come from words and phrases phrases written on plates, handmade ceramic figures made in Mexico or my studio, the Casa, and from current social events in the news. My goal is to create a tangible three-dimensional mosaic of an abstract concept or feeling using humor, whimsy or diametric opposites — such as good and evil — to make a statement.

As the mosaic comes together, my design morphs and evolves, often into something I had not anticipated. The need to remain flexible to let the process evolve is paramount. My imagination flourishes with the quiet and stillness from being in a wheelchair before visually exploding into a mosaic.

My altars are like nichos in Mexican folk art, although less like shrines and more humorous and quirkier with Day of the Dead figures to narrate a story. José Guadalupe Posada, the Mexican 19th-century lithographer and cartoonist, drew figures of La Catrina and calaveras, or skeletons, to represent and draw attention to differences in wealth and social class. By using the universality of death to make a statement about the living, he makes a powerful statement about the equality of all of us. I think of him often as I create my Day of the Dead Statue of Liberty series or my Women of the Supreme Court mosaics.

Like Posada, I can make social commentary using skeletons with whimsy and humor. I choose concepts of social justice, equality, women’s issues and current social events to inspire my altars. My altars reflect changing social and cultural norms. As with Posada’s cartoons, I reach people through humor. This is where my art and my activism come together.

In fact, blending my art and activism with my core value of social justice directs the content of my mosaic altars. Imagery and symbols are powerful. I use all types of imagery, from social stereotypes to cultural archetypes and diametric opposites, to make a visual representation of my perception of the world. Every choice I make, such as pairing symbols together heavy with meaning, shows my activism. We are all social activists in the daily choices we make.

Equity and fairness have always been my true north. I chose careers based on these beliefs. Studying medical entomology and working toward a career in tropical disease control to reduce infectious diseases within local areas was my goal until I suffered a massive catastrophic stroke in my late 20s.

A blood clot had lodged deep inside my brain stem, causing a massive loss of physical mobility. For several months afterward, doctors didn’t believe I would recover or return to independent living. Despite their pessimism, and with my paralyzed body and speech, I’ve been able to reframe my life and pursue a different career path that supports freedom of expression and independent living on my own terms.

As I processed my trauma, I returned to school to study social work. I focused on clinical social work specializing in family therapy as my way to be engaged with families living with a disability. I did this work for 20 years. In retrospect, I was the one who needed an alternative narrative to challenge the one I applied to myself: that my physical appearance and ability were not OK.

I was becoming aware of the enormous pressure I placed on myself to succeed. I knew I had to face my internalized stereotypes around disability. I had to separate myself from a medical model of disability, which had me feeling less than good enough, to a model of equality, inclusion and acceptance. This is where my previous attention and focus on activism and social justice saved me from myself.

Creating art was never on my list of career goals. I dabbled in art as a teenager, making candles, leather vests and macramé plant holders, which was something we all did in the 1960s. That was a part of myself that I left dormant as I pursued science. Yet 13 years ago, when I passed a storefront window displaying gorgeous mosaic sculptures full of movement and color, I got recharged. All those fractured abstract shapes put purposely back together to create a new form blew my mind and ignited my passion. There was something so familiar in this story, as if it described my story of putting myself back together in a different way.

I had to meet the artist at that very moment and went inside the shop. I discovered: The artist who created this art had experienced a stroke and built his mosaic sculptures one handed. Coincidence? Synchronicity? I’ll never know. I just knew I HAD to learn this art form. If he could do it, so could I.

I began by using a hammer and smashing 4-inch-by-4-inch tiles into shapes I wanted, then putting them back together. Soon I found I could gain more color and texture by replacing tile with porcelain plates. Thrift stores provided an endless supply of inspiration from plates to ceramic flowers and wooden candle holders that were discarded by others. I exchanged my hammer for tile nippers to slice a plate in the way you’d cut a pizza.

When the plate was too thick to cut myself, I’d wait for an unsuspecting friend to show up to make the cuts for me. In the beginning, I did a lot of my own cutting, but now, with my weakened hands, I needed to find more reliable hands.

The Magic of the Casa

I couldn’t keep asking my friends to help. I had to look toward others for the assistance I needed. The frustrating choice I had to make was to either invite others into my studio to continue making my art or stop making mosaics.

Translating my vision into words seemed exhausting, plus I wasn’t sure how outside “helping hands” could understand the complexities of my mosaics with their statement of humor and whimsy. The potential of changing my vision and design to accommodate the help I needed worried me most, believing that collaboration would interfere with my imagination. I continue to work through these issues with each mosaic I create.

Of course, passion won over doubts, as I invited one woman at a time into my welcoming creative space to do a particular task. It took several years for our community to evolve into a collective of artistic women who create together with a focus on my designs. I never imagined that I’d be in the role of an art director.

Together as a community, we have the freedom to express ourselves, inspire and hear each other and fully participate in the process of building mosaics without judgment. Our creative workspace builds on self-discovery, individual and collective competency-building and breaking into spontaneous, joyful play.

Without my “hands” from the brilliant women artists at the Casa, I could not do this work or express myself in this way. Calling ourselves a team lacks the intimacy of our relationships. As older women for whom isolation and feeling undervalued has become the norm, we have found connection in a meaningful way.

My inspiration comes from Mexican folk art and design.

The beautiful organic curves, scrolled shapes and vibrant colors replicating sunrises and sunsets make me want to capture them in a mosaic.

I’ve been collecting Mexican folk art ever since I was a child. This started when my uncle, who was living in Mexico, brought back Mexican art whenever he returned for a visit. Gradually, I refined my taste to collect primarily Day of the Dead-themed art.

The process for making mosaic altars begins by searching through my inventory of porcelain plates to find a palette of colors and texture that fits in with my idea of the mosaic I want to create.

My ideas come from words and phrases phrases written on plates, handmade ceramic figures made in Mexico or my studio, the Casa, and from current social events in the news. My goal is to create a tangible three-dimensional mosaic of an abstract concept or feeling using humor, whimsy or diametric opposites — such as good and evil — to make a statement.

As the mosaic comes together, my design morphs and evolves, often into something I had not anticipated. The need to remain flexible to let the process evolve is paramount. My imagination flourishes with the quiet and stillness from being in a wheelchair before visually exploding into a mosaic.

My altars are like nichos in Mexican folk art, although less like shrines and more humorous and quirkier with Day of the Dead figures to narrate a story. José Guadalupe Posada, the Mexican 19th-century lithographer and cartoonist, drew figures of La Catrina and calaveras, or skeletons, to represent and draw attention to differences in wealth and social class. By using the universality of death to make a statement about the living, he makes a powerful statement about the equality of all of us. I think of him often as I create my Day of the Dead Statue of Liberty series or my Women of the Supreme Court mosaics.

Like Posada, I can make social commentary using skeletons with whimsy and humor. I choose concepts of social justice, equality, women’s issues and current social events to inspire my altars. My altars reflect changing social and cultural norms. As with Posada’s cartoons, I reach people through humor. This is where my art and my activism come together.

In fact, blending my art and activism with my core value of social justice directs the content of my mosaic altars. Imagery and symbols are powerful. I use all types of imagery, from social stereotypes to cultural archetypes and diametric opposites, to make a visual representation of my perception of the world. Every choice I make, such as pairing symbols together heavy with meaning, shows my activism. We are all social activists in the daily choices we make.

Equity and fairness have always been my true north. I chose careers based on these beliefs. Studying medical entomology and working toward a career in tropical disease control to reduce infectious diseases within local areas was my goal until I suffered a massive catastrophic stroke in my late 20s.

A blood clot had lodged deep inside my brain stem, causing a massive loss of physical mobility. For several months afterward, doctors didn’t believe I would recover or return to independent living. Despite their pessimism, and with my paralyzed body and speech, I’ve been able to reframe my life and pursue a different career path that supports freedom of expression and independent living on my own terms.

As I processed my trauma, I returned to school to study social work. I focused on clinical social work specializing in family therapy as my way to be engaged with families living with a disability. I did this work for 20 years. In retrospect, I was the one who needed an alternative narrative to challenge the one I applied to myself: that my physical appearance and ability were not OK.

I was becoming aware of the enormous pressure I placed on myself to succeed. I knew I had to face my internalized stereotypes around disability. I had to separate myself from a medical model of disability, which had me feeling less than good enough, to a model of equality, inclusion and acceptance. This is where my previous attention and focus on activism and social justice saved me from myself.

Creating art was never on my list of career goals. I dabbled in art as a teenager, making candles, leather vests and macramé plant holders, which was something we all did in the 1960s. That was a part of myself that I left dormant as I pursued science. Yet 13 years ago, when I passed a storefront window displaying gorgeous mosaic sculptures full of movement and color, I got recharged. All those fractured abstract shapes put purposely back together to create a new form blew my mind and ignited my passion. There was something so familiar in this story, as if it described my story of putting myself back together in a different way.

I had to meet the artist at that very moment and went inside the shop. I discovered: The artist who created this art had experienced a stroke and built his mosaic sculptures one handed. Coincidence? Synchronicity? I’ll never know. I just knew I HAD to learn this art form. If he could do it, so could I.

I began by using a hammer and smashing 4-inch-by-4-inch tiles into shapes I wanted, then putting them back together. Soon I found I could gain more color and texture by replacing tile with porcelain plates. Thrift stores provided an endless supply of inspiration from plates to ceramic flowers and wooden candle holders that were discarded by others. I exchanged my hammer for tile nippers to slice a plate in the way you’d cut a pizza.

When the plate was too thick to cut myself, I’d wait for an unsuspecting friend to show up to make the cuts for me. In the beginning, I did a lot of my own cutting, but now, with my weakened hands, I needed to find more reliable hands.

The Magic of the Casa

I couldn’t keep asking my friends to help. I had to look toward others for the assistance I needed. The frustrating choice I had to make was to either invite others into my studio to continue making my art or stop making mosaics.

Translating my vision into words seemed exhausting, plus I wasn’t sure how outside “helping hands” could understand the complexities of my mosaics with their statement of humor and whimsy. The potential of changing my vision and design to accommodate the help I needed worried me most, believing that collaboration would interfere with my imagination. I continue to work through these issues with each mosaic I create.

Of course, passion won over doubts, as I invited one woman at a time into my welcoming creative space to do a particular task. It took several years for our community to evolve into a collective of artistic women who create together with a focus on my designs. I never imagined that I’d be in the role of an art director.

Together as a community, we have the freedom to express ourselves, inspire and hear each other and fully participate in the process of building mosaics without judgment. Our creative workspace builds on self-discovery, individual and collective competency-building and breaking into spontaneous, joyful play.

Without my “hands” from the brilliant women artists at the Casa, I could not do this work or express myself in this way. Calling ourselves a team lacks the intimacy of our relationships. As older women for whom isolation and feeling undervalued has become the norm, we have found connection in a meaningful way.