I grew up in the Dorset / Hampshire area in the countryside of southwest England. The house we grew up in was an old game keeper’s cottage my mother and father found in 1984. The walls are wonky and corners are round. We were off grid and had no electricity, just a generator for power. My mother is a painter and florist, and every inch of the walls in our house are covered in her paintings, from landscapes to paintings of birds and flowers. I’ve always thought of the walls of the house being a time line of our lives. My father used to run a vintage cloths shop called Biggles before I was born. When he and my mother split up I was seven. I remember he picked ivy and hydrangeas to sell to florists and would roam carboot sales for precious items to sell. He used to collect us from school in a Citroen C15 van with a boot full of ivy and hundreds of spiders hanging from the ceiling. We would refuse to get in, but he never once removed the spiders on the basis they were his friends. I remember many fearful journeys in that van in the front seat with my sister (because the back was filled with ivy) huddled together trying not to look up at the spiders clustered in the corners.

I was lucky to be surrounded by visual artists and creatively minded people. We spent a lot of time in Cornwall with my mother near Lands End where we would explore rock pools, go on windy cliff walks and then shelter inside and spend the afternoons round a table drawing and painting. My mother introduced me to the world of naïve painters like the St Ives set. For example, Alfred Wallis, Barbara Hepworth, Ben Nicholson, whose art left a huge impression on me.

I was lucky to be surrounded by visual artists and creatively minded people. We spent a lot of time in Cornwall with my mother near Lands End where we would explore rock pools, go on windy cliff walks and then shelter inside and spend the afternoons round a table drawing and painting. My mother introduced me to the world of naïve painters like the St Ives set. For example, Alfred Wallis, Barbara Hepworth, Ben Nicholson, whose art left a huge impression on me.

One artist in particular who has been a big inspiration for me is the painter Tim Nicholson, son of EQ Nicholson, a relation of Ben Nicholson. He lived down the road from us in Cranbourne chase and we spent a lot of time as kids at his house.

When at home, we would spend most of our time outside playing in the woods, exploring and making dens. We had quite a rustic upbringing. There was never much money, but we had a very colourful time, which I feel very grateful for now.

I think when you spend time studying something in order to draw it you discover a new sensibility and tenderness towards that entity or place. I find this makes me feel very close to the natural world. For example, if you learn the name of a plant then you go on a walk and you encounter it growing, being able to name it gives you a whole new relationship to it and is inspiring and exciting. You create an intimate relationship with the subject.

I was surrounded by artists and was always encouraged to draw and paint from a young age. One of my earliest memories is of being five in my mother’s flower shop at the Fisherton Mill in Salisbury. I used to accompany her and would spend my time making bouquets of flowers to sell at the end of the lane to passers by. Then I would buy ice cream. We also spent hours making dens in the woods and fields behind the house. Just before the farmer would cut the grass to make hay, we would roll the grass out and make elabo- rate labyrinths with long corridors, which would lead to secret rooms.

My fiancé (who is a musician and artist) and I influence each other’s work a lot. I make artwork for him from the inks we’ve made together and we spend hours coming up with costume ideas for his performances and becoming obsessed with new creative pursuits, for example, embroidery, darning and bookbinding just to list a few.

One of the projects we have made together is a sunflower dance troupe. I made giant sunflower masks out of cardboard, tissue paper and wire that you wear on your head and leaf gloves you slot onto your hands. We then choreographed a dance routine based on the movements of a sun- flower following the sun, and much to my surprise have since toured together all over Europe, North America and Japan.

One of the projects we have made together is a sunflower dance troupe. I made giant sunflower masks out of cardboard, tissue paper and wire that you wear on your head and leaf gloves you slot onto your hands. We then choreographed a dance routine based on the movements of a sun- flower following the sun, and much to my surprise have since toured together all over Europe, North America and Japan.

I think I realised at a young age that art was a language I could speak. I found words harder to express myself with and struggled in school, but with drawing and painting I felt confident and more able to communicate. I remember in school when I was about ten, we were learning about the Holocaust and I was chosen to paint a response to what we had learnt. I used charcoal and I drew lots of bodies lying on a heap behind a barbed wire fence. It was on display in the front of the school with some of the other kids’ drawings and representation of the war. I remember realising the potential power of imagery to communicate my feelings and reflections and the effect it could have on others.

didn’t like the approach and left university to go and apprentice in Spain with a sculptor called Cristobel Martin. He worked mainly with bronze and lived in the mountains just west of Madrid with his family. He is Sufi and a lot of his work is influenced by his faith and his spiritual practices. He saw the world as being alive with beauty, which was very much reflected through his sculptures. I stayed with him and his family for two months and became inspired with the intimacy and physicality of sculpture.

Ceramics came a little later than painting and drawing. I had been studying fine art at university, but didn’t like the approach and left university to go and apprentice in Spain with a sculptor called Cristobel Martin. He worked mainly with bronze and lived in the mountains just west of Madrid with his family. He is Sufi and a lot of his work is influenced by his faith and his spiritual practices. He saw the world as being alive with beauty, which was very much reflected through his sculptures. I stayed with him and his family for two months and became inspired with the intimacy and physicality of sculpture.

Upon return I applied to Brighton University to do material practice and design. We were taught the basics of four mediums, metal, plastics, wood and ceramics. I ended up finding ceramics the most inspiring and mysterious. It’s an almost alchemical process and one where there is always an unexpected element. You’re never entirely sure what’s going to come out the other side. My interests in making inks began after I was given some acorn ink by an amazing forager called Anna Richardson. It was by far the most characterful ink I had ever used and planted a seed in my mind, but I didn’t do anything about it until a book by the Toronto-based ink forager Jason Logan was left on the kitchen table by my house- mates. Thus the love affair began. It was autumn, a particularly bountiful time with many things to extract colour from. I loved being able to preserve the changing colourworlds of the seasons, and the encounters with places and plants that these colours would represent.

I share my mum’s studio at the cottage in Dorset, where I spend lots of time foraging materials for ink making. I also have a studio near Tottenham area in London where I make ceramics. It is a communal space I share with three other artists, a textile art- ist, a wood worker and a ceramist. We run ceramic courses there, so it’s often very lively with lots of people bustling around making a wide variety of things. For me it is important to have this balance between the city and the countryside, as spending time at home is often where I get lots of ideas and inspiration from.

I share my mum’s studio at the cottage in Dorset, where I spend lots of time foraging materials for ink making. I also have a studio near Tottenham area in London where I make ceramics. It is a communal space I share with three other artists, a textile art- ist, a wood worker and a ceramist. We run ceramic courses there, so it’s often very lively with lots of people bustling around making a wide variety of things. For me it is important to have this balance between the city and the countryside, as spending time at home is often where I get lots of ideas and inspiration from.

Often my different creative practices overlap and influence each other. For example, I have worked lots as a freelance florist, and grew up working on flower jobs with my mother. I have often been struck by how much waste is produced by floristry. Flower installations are usually temporary. The flowers are thrown away a day after they have been installed, which is always hard to watch. Rather than let these wonderful botanical riches go to waste, I have been turning them into inks, some of which I sell through Jam Jar (a floristry company I collaborate with).

These inks influence the way I draw, as each ink behaves in its own unique way. And these inks and drawings in turn influence my ceramics. So in a way the ink making has woven many of my practices and interests together.

Much of my work is an attempt to imbue a sense of place into an object, an image or an ink. I explored this theme of place in my ceramic objects by taking the process of making out of the studio and into various different locations. For example I made a series of vessels up on a hill next to a windmill on the Sussex coast and another series down on a pebbly beach in a gale force wind. I called these vessels wind- swept pots, as they were quite literally blown by the wind. I made another series in an urban environment underneath some railway tracks in mid winter. It was very cold and rainy. The vessels ended up looking ridged, awkward and ugly. For one of my other projects, I created tools from found objects in three different locations, took them back to the studio, and used them to make ceramic objects. At the time, I was heavily influenced by the writings of the psychogeographers and the situationists and wanted to explore how making things outside of the studio environment would influence the pieces.

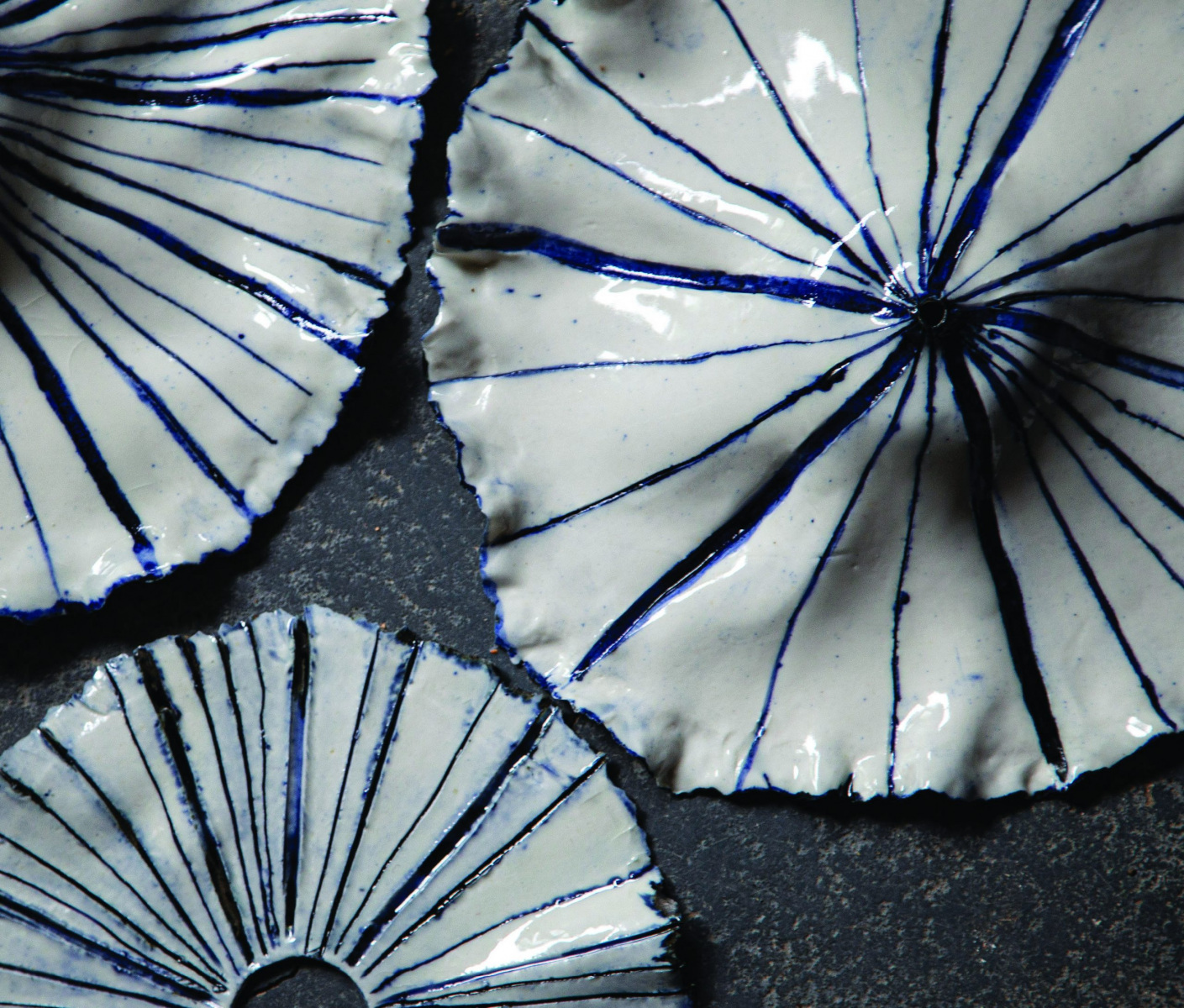

By pinching, pulling and moulding the edges of the clay with my fingers, I try to capture a sense of movement, similar to the undulations of a jellyfish or a stingray as they move through the water. Porcelain when fired has beautiful translucent qualities so I etch into the clay body to create depth in light. I make hand built ceramics as I love the uneven textures that can be left by the hand, and the way that it reveals the process by which it is made.

There is a book by Richard Maybe called Weeds: the story of outlaw plants. He shows how a plant can become a weed just by growing in the “wrong place”. The book talks about the social history of plants and how our attitude to weeds can tell us so much about human society. I find this book endlessly inspiring.

“Weeds thrive in the company of humans. They aren’t parasites, because they can exist without us, but we are their natural ecological partners, the species alongside which they do best. They relish the things we do to the soil: clearing forests, digging, farming, dumping nutrient-rich rubbish. They flourish in arable fields, battlefields, parking lots, herbaceous borders. They exploit our transport systems, our cooking adventures, our obsession with packaging. Above all they use us when we stir the world up, disrupt its settled patterns. It would be a tautology to say that these days they are found most abundantly where there is most weeding; but that notion ought to make us question whether the weeding encourages the weeds as much as vice versa.”

RICHARD MABEY

It is often only after or through making I am working towards an exhibition alongside my something that I come to fully appreciate the various threads of inspiration that have given rise to it. I find that a lot of my inspiration comes from observing natural forms, and thinking about the different perceptual experiences of animals, plants and fungi. One long term project of mine has been doing a series of fish paintings inspired by my father’s fishing journal from when he was a child. His journal, written between the ages of seven to eighteen, contained detailed descriptions of the weather, the colour and the character of the fish he encountered. What is it like to be a fish? I started drawing fish based on his descriptions and this developed into various studies of the river fish of Britain. One of the other things that really inspires me is exploring and thinking about the value that people place on objects and the way that stories make the meaning that objects hold. This feels especially important in a society where objects are so easily discarded and manufactured for single use.

I am working towards an exhibition alongside my mother based on our relationship to home as it has been one of the biggest sources of inspiration for us both. We will be using a variety of mediums, including paintings, ceramics, inks and drawings. And I am beginning to explore the relationships between ceramics and movement with a friend of mine who is a movement therapist. I very much like working with people from different artistic backgrounds, it can be very inspiring to see the way other artists work in relation to how you work.