I HAVE TRIED TO WRITE about the questions I ask myself about my specific form of art-making, about the chosen medium, about all those solitary hours I spend in the studio. For more than 20 years, my creations were made mostly with wool. I made all kinds of things, really: toys, scarves, dresses and handbags, but also wall hangings, sculptures and fantastic costumes. If the medium is the message, as the Canadian Marshall McLuhan stated, then what does this material reveal?

But why this wool? Why the love for felt? Why the love for felt-making? The wool is light and feral. It comes in so many colours and characters and qualities that surprise but also give tranquility because it feels so strangely common. It is chaotic and wild and untamed, still so close to the animal who grows it generously several times a year.

Then there’s the craft of felting, the entangling of the fibers to a sturdy, solid sculptable material. Felted, that fluffy soft hair is caught in a material that looks like something close to animal hide, maybe even our own skin.

As wool, it is free and flowing; but as felt, it is imprisoned by its own hair.

A substance that gives us protection, warmth, insulation — but its density can also invite sensations of breathlessness, maybe even suffocation.

The feel of wool is inviting to touch. We felters can’t resist the allure of its possibilities: the laying out of the carefully combed or carded fibers, designs with intricate patterns and forms, fascinating color combinations, placing the wool filaments in all kinds of directions — sometimes mixed with silks or other fibers. This painting, this shingling — hair by hair — done with presence and attention is calming for the mind. The result is enchanting.

Everything changes when we start to felt — adding the soapy water, the rubbing and rolling, the endless massaging (ever wondered what is behind that need to caress our material for hours, maybe every day?). Gently, to start with, to give the wool time to come together, and then, working with more force, entangling it forever in a new form.

The final hardening and shaping are intense and sometimes almost violent, especially when the final work is voluminous and heavy in weight.

The intense physical labour can be very gratifying when making very large pieces — almost a “peak” experience. It can take months to prepare, and it can be physically painful to the body, but getting there is very satisfying.

THE ALIVENESS OF THIS MEDIUM makes it feel close to our skin. The fact that we make it almost solely with our hands with no tools or screens, and the experience of shaping the wool only with touch into a completely unique creation, is outstanding. Sometimes, it feels as if the making is more important than what is made.

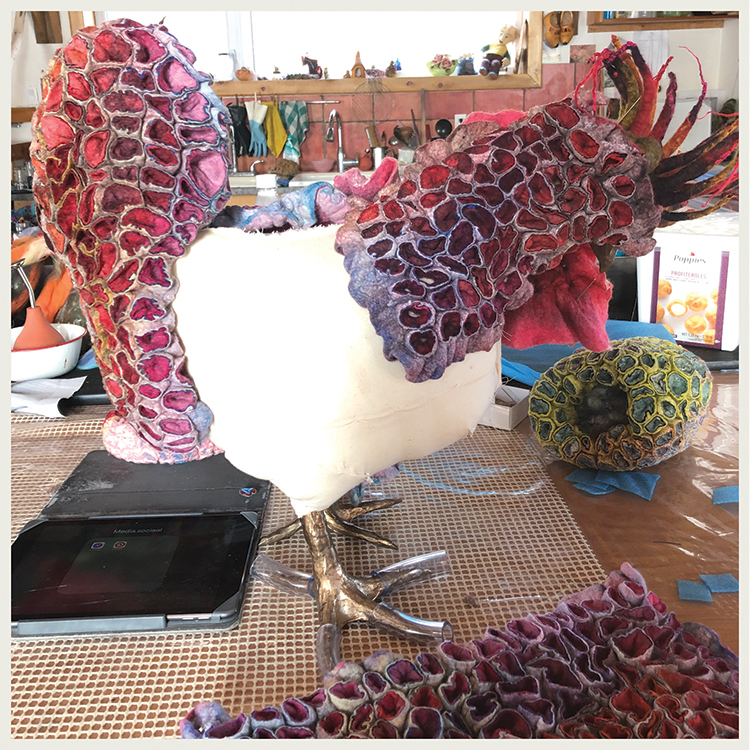

FLAMBEAU & LITTLE SEDNA

I HAVE TRIED TO WRITE about the questions I ask myself about my specific form of art-making, about the chosen medium, about all those solitary hours I spend in the studio. For more than 20 years, my creations were made mostly with wool. I made all kinds of things, really: toys, scarves, dresses and handbags, but also wall hangings, sculptures and fantastic costumes. If the medium is the message, as the Canadian Marshall McLuhan stated, then what does this material reveal?

But why this wool? Why the love for felt? Why the love for felt-making? The wool is light and feral. It comes in so many colours and characters and qualities that surprise but also give tranquility because it feels so strangely common. It is chaotic and wild and untamed, still so close to the animal who grows it generously several times a year.

Then there’s the craft of felting, the entangling of the fibers to a sturdy, solid sculptable material. Felted, that fluffy soft hair is caught in a material that looks like something close to animal hide, maybe even our own skin.

As wool, it is free and flowing; but as felt, it is imprisoned by its own hair.

A substance that gives us protection, warmth, insulation — but its density can also invite sensations of breathlessness, maybe even suffocation.

The feel of wool is inviting to touch. We felters can’t resist the allure of its possibilities: the laying out of the carefully combed or carded fibers, designs with intricate patterns and forms, fascinating color combinations, placing the wool filaments in all kinds of directions — sometimes mixed with silks or other fibers. This painting, this shingling — hair by hair — done with presence and attention is calming for the mind. The result is enchanting.

Everything changes when we start to felt — adding the soapy water, the rubbing and rolling, the endless massaging (ever wondered what is behind that need to caress our material for hours, maybe every day?). Gently, to start with, to give the wool time to come together, and then, working with more force, entangling it forever in a new form.

The final hardening and shaping are intense and sometimes almost violent, especially when the final work is voluminous and heavy in weight.

The intense physical labour can be very gratifying when making very large pieces — almost a “peak” experience. It can take months to prepare, and it can be physically painful to the body, but getting there is very satisfying.

THE ALIVENESS OF THIS MEDIUM makes it feel close to our skin. The fact that we make it almost solely with our hands with no tools or screens, and the experience of shaping the wool only with touch into a completely unique creation, is outstanding. Sometimes, it feels as if the making is more important than what is made.

FLAMBEAU & LITTLE SEDNA