I didn’t seek out hats: Hats found me. I had originally wanted to study English literature but, long story short, I ended up studying costume making, and one component of that course was millinery. One thing led to another and, 20 years later, I’m a theatrical milliner.

I’ve had quite a few different occupations along the way and worked for some remarkable people. Nowadays I work for myself, and I have a small studio in Nottingham (shared with a costume maker), and teach costume making at Nottingham Trent University.

I was always ambitious at university, but I knew I did not want to be a costume designer. When I sidestepped into millinery, I worked for a variety of milliners — both in Australia and the U.K. One of the more typical career progressions for milliners is to take some classes, then work for some established milliners (ideally, for a few years), and then set up for one’s self.

I spent five years working in the London studio of hat designer Philip Treacy and saw how hard it was being one of the most famous and talented milliners in the world. I had never sought fame of that sort, in any case; and after leaving London in 2013, I enjoyed a few years of taking time to figure out what sort of milliner I was.

Now, in 2023, I combine my couture millinery skills with those of the hilariously varied world of costume. No two days are the same. Rarely are two hat orders the same! I also have never aspired to be a designer. Rather, my enjoyment from making comes from the problem-solving aspect.

I’ve always had a passion for historical fashion and began collecting 19th-century bonnets in 2018. My collection now numbers more than a dozen and, in studying and reproducing versions of them, I have found the perfect combination of making and research.

Process for Creating 1830s Reproduction Bonnet

This bonnet was the sixth incarnation of the original 1830s extant garment. Each had its own reason for being created, but this one was specifically to go on display in an exhibition of 1830s costumes and fashion in Halifax, U.K. (Fashion in Anne Lister’s Time, Bankfield Museum, 2022).

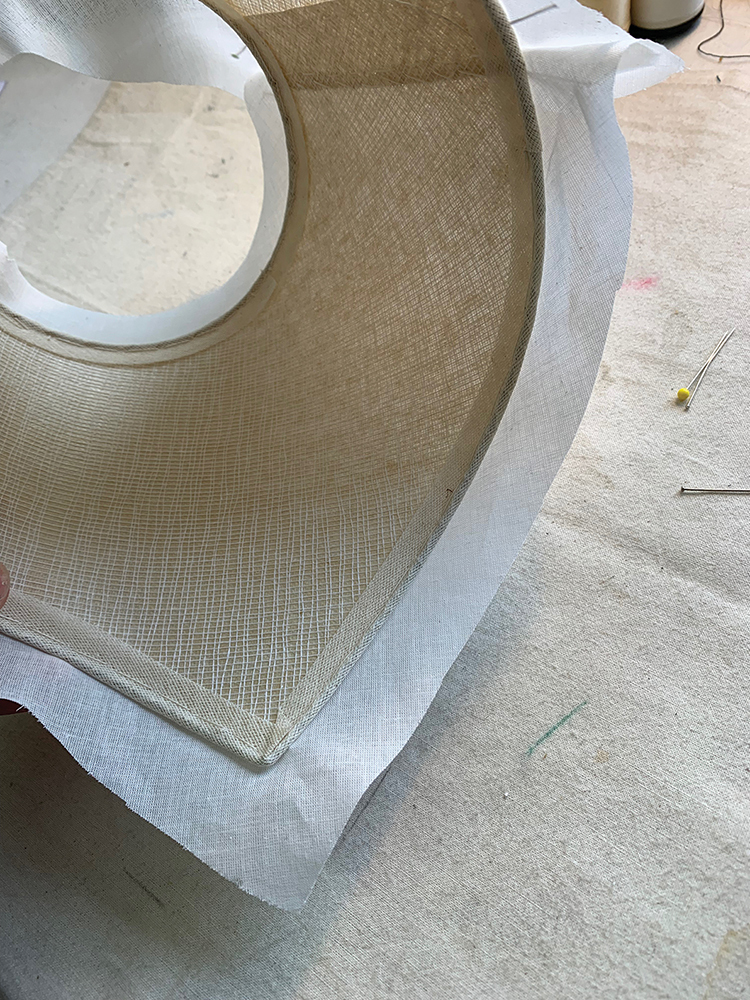

The aim with this bonnet was to use materials as close as I could find to 1830s originals. Garments of that period, and throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, were made of significantly lighter fabrics than we generally have available today. The weight of the fabric and materials inside the bonnet make a significant impact on the weight of the finished hat.

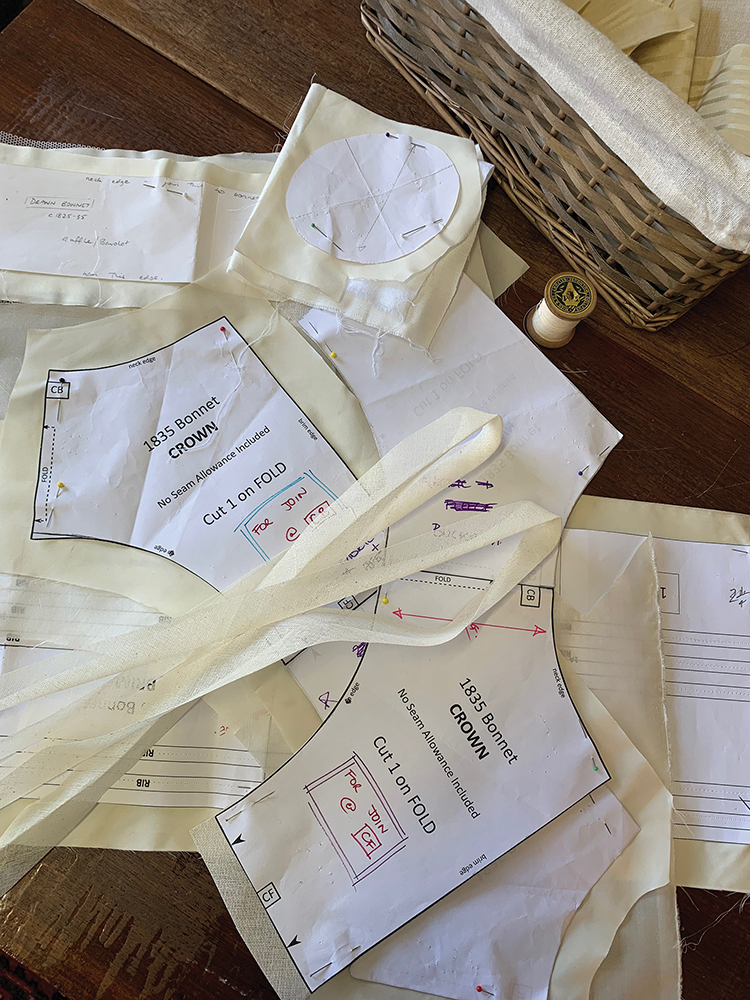

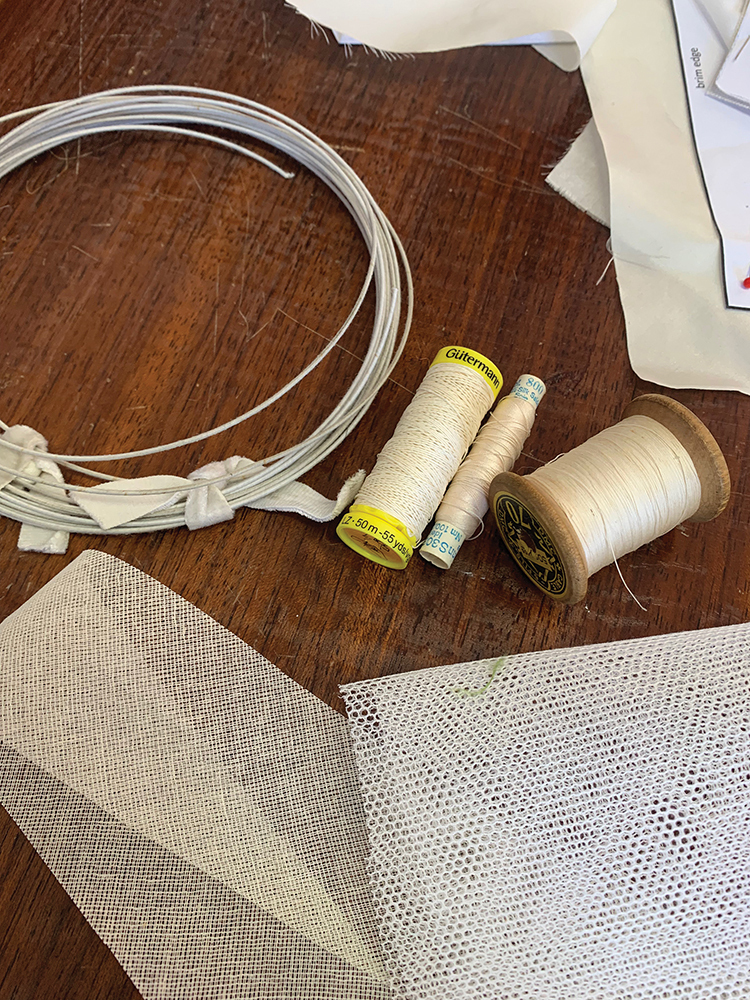

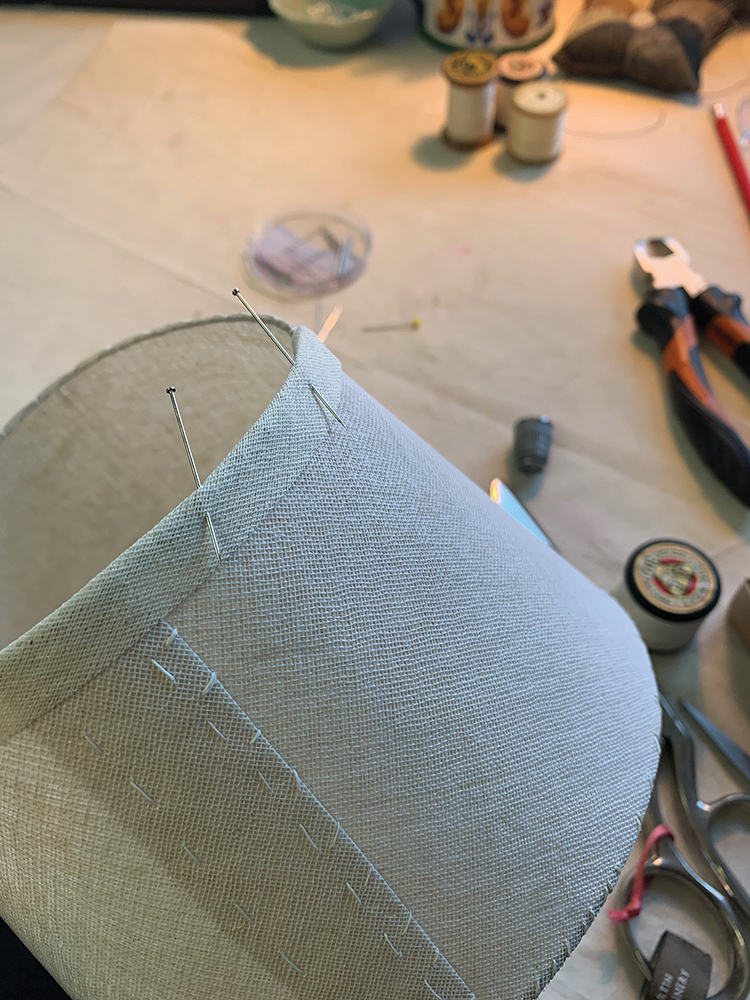

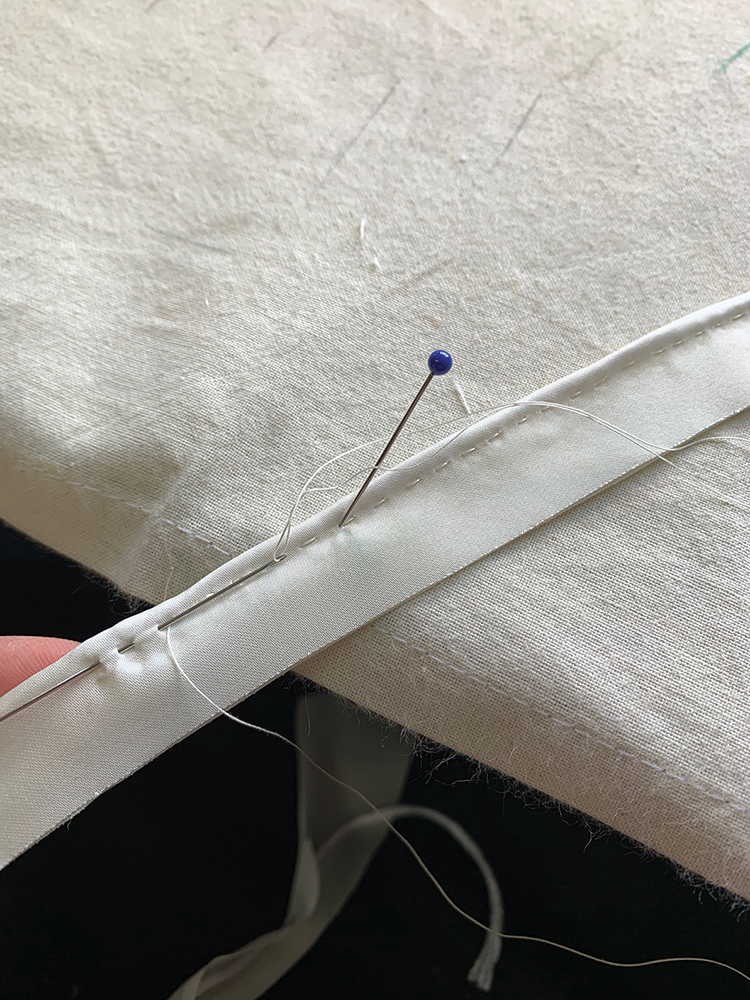

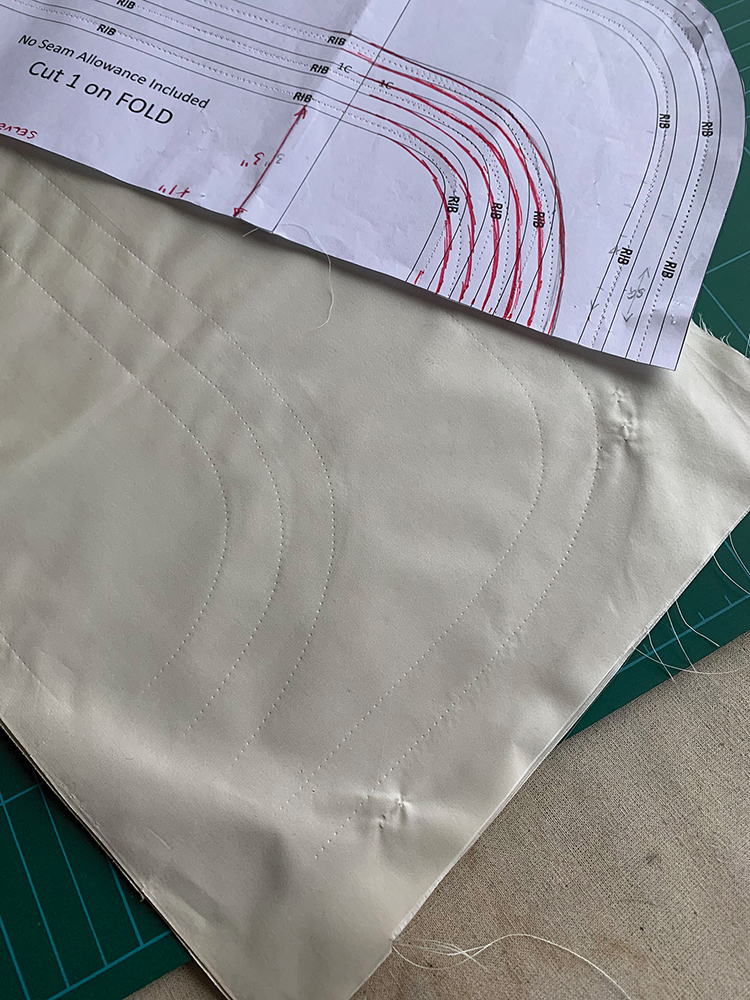

I selected a beautiful ivory silk taffeta, sourced in Birmingham, for the main fabric of the hat, and used a remnant of a vellum-type buckram for the structure of the crown. The wires I used were all thin but strong. To get the seams to behave properly, I used a very fine vintage cotton thread and correspondingly fine needle in order to get the smallest and neatest seams possible.

I consider materials and equipment to be absolutely essential in achieving the highest level of work I can. This does not mean the most expensive, nor the most obscure or esteemed. Twenty years of making hats and costumes has given me a knowledge of materials that is invaluable. Even with this knowledge, sampling and trying things out before I create the real piece is essential. I need to know how a fabric will drape and fall, if it will fray, how it will handle stitching and pressing. Equipment and tools are more of a personal preference. I have very specific sizes and types of needles I use, and I’m particular about threads.

The construction of these bonnets has become more straightforward with each one made, but I do refer to the original 1830s bonnet constantly to see the techniques and methods. I only alter the original methods when I see things that might have been specific to the maker, i.e., a wonky seam that should really be straight. The benefit of having invested in real period headwear is that I can examine them at my leisure and handle them more than I might in a museum or archive. In my collection, I currently have bonnets dating between 1830 and 1880, plus some other hats from 1870 to 1920.

I didn’t seek out hats: Hats found me. I had originally wanted to study English literature but, long story short, I ended up studying costume making, and one component of that course was millinery. One thing led to another and, 20 years later, I’m a theatrical milliner.

I’ve had quite a few different occupations along the way and worked for some remarkable people. Nowadays I work for myself, and I have a small studio in Nottingham (shared with a costume maker), and teach costume making at Nottingham Trent University.

I was always ambitious at university, but I knew I did not want to be a costume designer. When I sidestepped into millinery, I worked for a variety of milliners — both in Australia and the U.K. One of the more typical career progressions for milliners is to take some classes, then work for some established milliners (ideally, for a few years), and then set up for one’s self.

I spent five years working in the London studio of hat designer Philip Treacy and saw how hard it was being one of the most famous and talented milliners in the world. I had never sought fame of that sort, in any case; and after leaving London in 2013, I enjoyed a few years of taking time to figure out what sort of milliner I was.

Now, in 2023, I combine my couture millinery skills with those of the hilariously varied world of costume. No two days are the same. Rarely are two hat orders the same! I also have never aspired to be a designer. Rather, my enjoyment from making comes from the problem-solving aspect.

I’ve always had a passion for historical fashion and began collecting 19th-century bonnets in 2018. My collection now numbers more than a dozen and, in studying and reproducing versions of them, I have found the perfect combination of making and research.

Process for Creating 1830s Reproduction Bonnet

This bonnet was the sixth incarnation of the original 1830s extant garment. Each had its own reason for being created, but this one was specifically to go on display in an exhibition of 1830s costumes and fashion in Halifax, U.K. (Fashion in Anne Lister’s Time, Bankfield Museum, 2022).

The aim with this bonnet was to use materials as close as I could find to 1830s originals. Garments of that period, and throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, were made of significantly lighter fabrics than we generally have available today. The weight of the fabric and materials inside the bonnet make a significant impact on the weight of the finished hat.

I selected a beautiful ivory silk taffeta, sourced in Birmingham, for the main fabric of the hat, and used a remnant of a vellum-type buckram for the structure of the crown. The wires I used were all thin but strong. To get the seams to behave properly, I used a very fine vintage cotton thread and correspondingly fine needle in order to get the smallest and neatest seams possible.

I consider materials and equipment to be absolutely essential in achieving the highest level of work I can. This does not mean the most expensive, nor the most obscure or esteemed. Twenty years of making hats and costumes has given me a knowledge of materials that is invaluable. Even with this knowledge, sampling and trying things out before I create the real piece is essential. I need to know how a fabric will drape and fall, if it will fray, how it will handle stitching and pressing. Equipment and tools are more of a personal preference. I have very specific sizes and types of needles I use, and I’m particular about threads.

The construction of these bonnets has become more straightforward with each one made, but I do refer to the original 1830s bonnet constantly to see the techniques and methods. I only alter the original methods when I see things that might have been specific to the maker, i.e., a wonky seam that should really be straight. The benefit of having invested in real period headwear is that I can examine them at my leisure and handle them more than I might in a museum or archive. In my collection, I currently have bonnets dating between 1830 and 1880, plus some other hats from 1870 to 1920.