My husband doesn’t believe in lawns. He’d be happier, he says, with pebbles.

Not willing to exchange green and buds for dusty stones, I’ve done all the green things throughout our marriage. Planted the bushes and seeds, tended the bulbs, paid the kids with the lawn mowers, gone out just after dawn or just before dusk and watered the unquenched, slapping all the while at the bugs that swarm around my head. We live on a small plot of land that was once part of a golf course that belonged to a country sprawl of a hotel, one of the finest hotels there ever was, more than a century ago.

Oh, if the elite could see us now.

But last year the kid with the lawnmower committed some fire-able offenses (like driving his machine repeatedly into our house and rattling the stucco; like running over and through the garden I’d been tending), and so I fired him. After that, there was no one willing to do the mowing for a plot of land as small and unremunerative as ours, and so all lawn maintenance came to a halt.

Our grass grew knee high.

I lived in shame. Finally, humiliation and adrenaline got the better of me. I snapped off the evening news, hiked through the green wilderness and cried big tears as I stood before our nearest, lawn-attentive neighbor.

“Please can we borrow your mower,” I said. Begged, might be the word.

Three weeks later, our borrowing days done, our own lawn mower arrived. And that’s how my husband became, at last, an actual one-yard lawn-maintenance guy.

Our economy mower is the kind you push, not the kind you ride. It’s the kind most people would stow in a garage, except we have no garage. It’s battery operated, no gas. All of this, my husband has taken in stride. Once a week during the height of grass-growing season, you can find him at an early hour, making pretty mowing patterns.

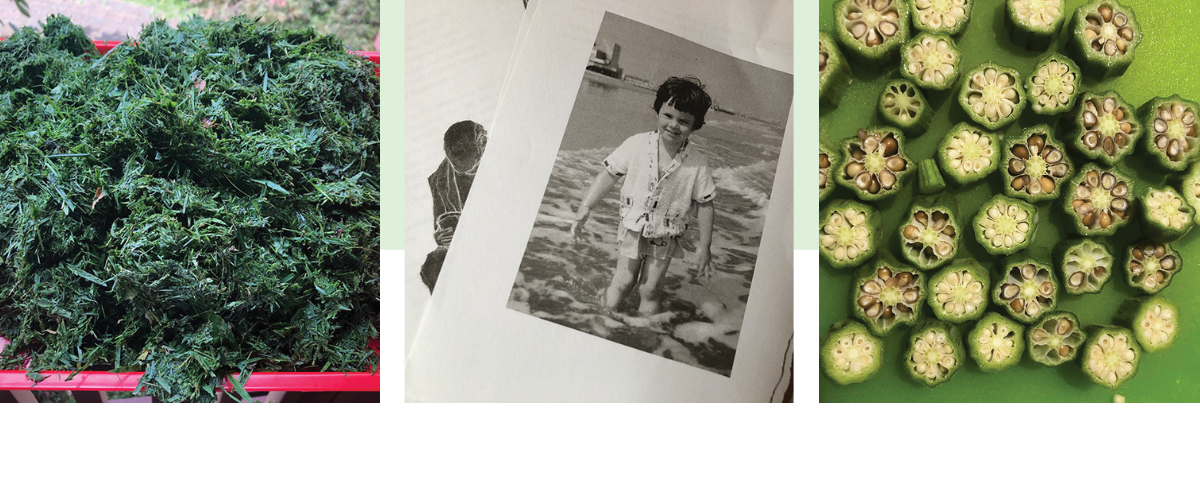

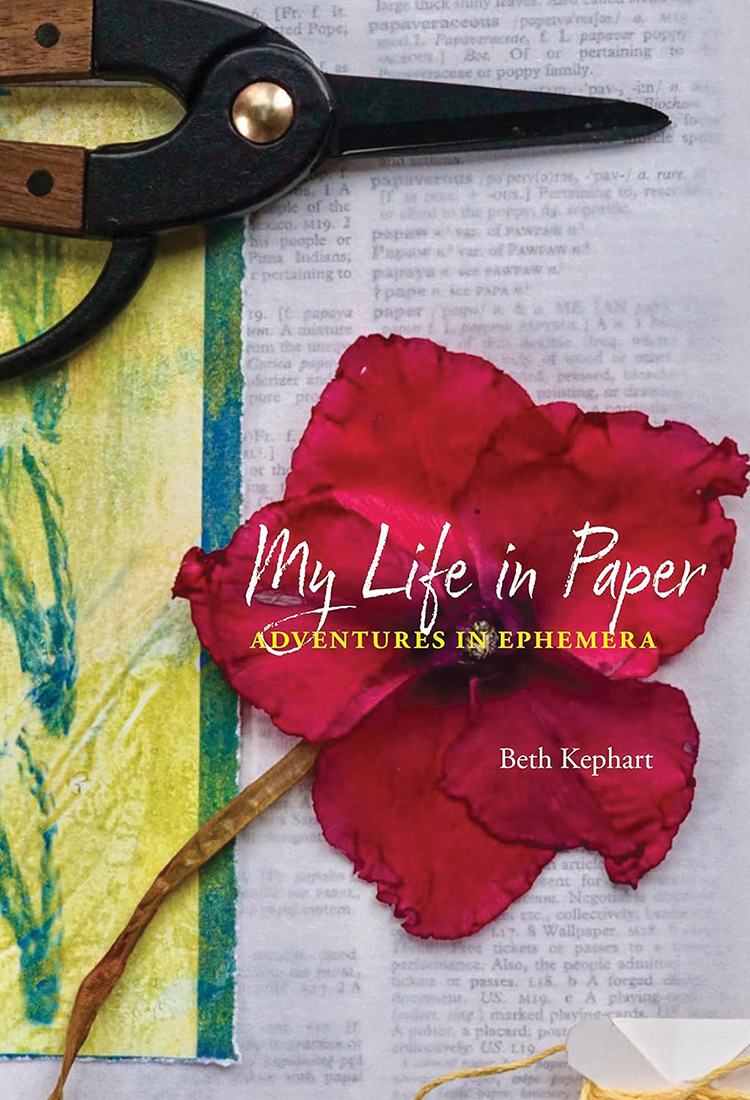

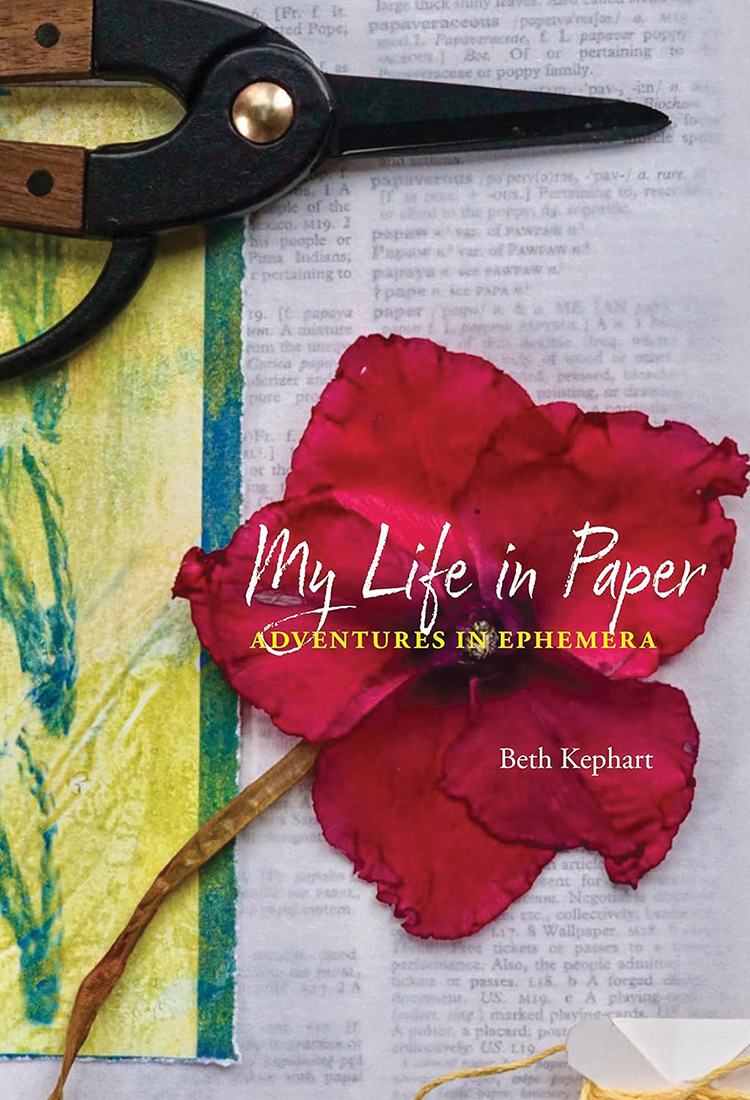

Several weeks ago, my husband, after announcing a return to “Best in Neighborhood” status, also announced this: “I left all the cut grass in a pile by the trash can, in case you want to do something with it.”

“Do something with it?” I repeated, tilting the end of my sentence with a question-mark sound. Then I remembered something I’d mentioned casually long ago: “Someday,” I’d declared, “I’ll make grass paper.”

Grass paper already exists, of course. This was not some grand, original notion of mine. Like the leaves of irises and yucca plants or the skins of onions or the stalks of cattails (minus the cigars), grass is a wonderful paper-making material. A miracle of cellulose, chlorophyll and water, grass is fibrous.

When you cut it up and drop it (carefully) in a non-aluminum pot of washing-soda-enhanced water, you have before you the start of something — fibers breaking away from fibers so that they may come together again as paper. Accelerate the process by rinsing the macerated grass and pouring it into a blender. Then ball the strained blendered stuff up and place it on a sturdy surface. Find a pair of wide wooden sticks.

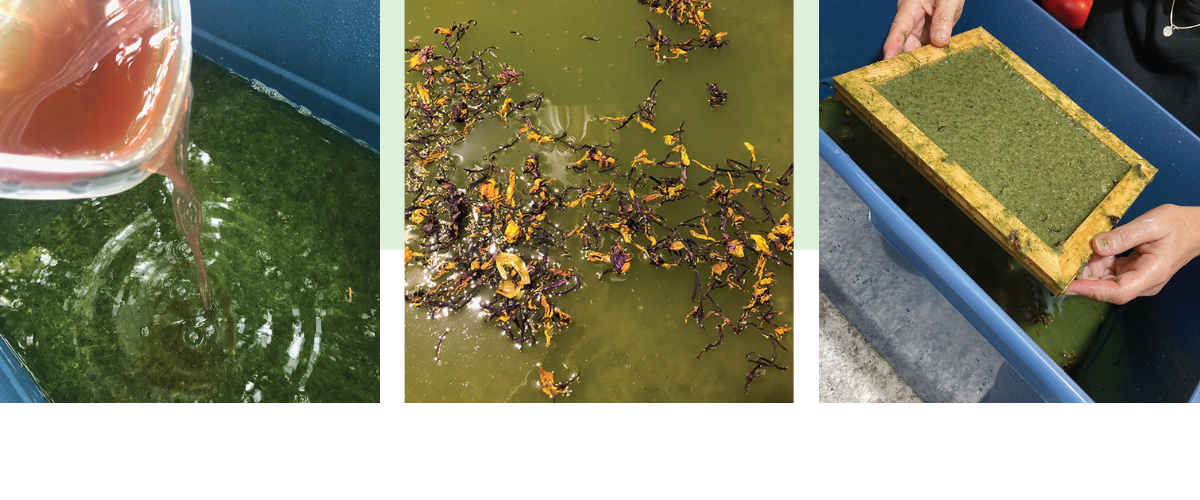

Pound. Pretend you are playing the drums. What you’re doing is very noble. You are freeing fibers.

I had some smelly fun with this.

I did the work outside, so as not to contaminate my kitchen. I got my husband involved with the makeshift apparatus, the straining, the drumming. The mosquitoes arrived uninvited. Once my grass fibers were as free as they were ever going to be, I dumped them into a vat of clean water, threw in some shredded paper, tossed in some okra juice (I’d boiled sliced okra and saved the slime; the slime is a formation aid), and stirred the whole thing up with my hand. Then I grabbed my little mold and deckle. I dipped. I gently shook. I let the water drain.

There, on the face of my mold was the start of a piece of paper — by which I mean beaten and soaked grass fibers attaching to beaten and soaked grass fibers. Of course, the thin wet sheet would have to be removed from the mold, layered between old cotton T-shirts and dried (along with other sheets) beneath a slab of marble. Of course, this drying thing would test my patience. But at the end of it all, a few days later, I had myself something I had not had before, made of grass that always knew, in its green heart, that it was anything but trash.

A Step-by-Step Guide to the Making of Grass Paper

(Materials and tools indicated in bold print)

1. Collect the mowed grass. Four healthy-sized handfuls should do the trick. Gratitude toward the lawn mower helps to ensure future supplies.

2. Shred some existing paper. I find that this gives the paper you are making more strength and character.

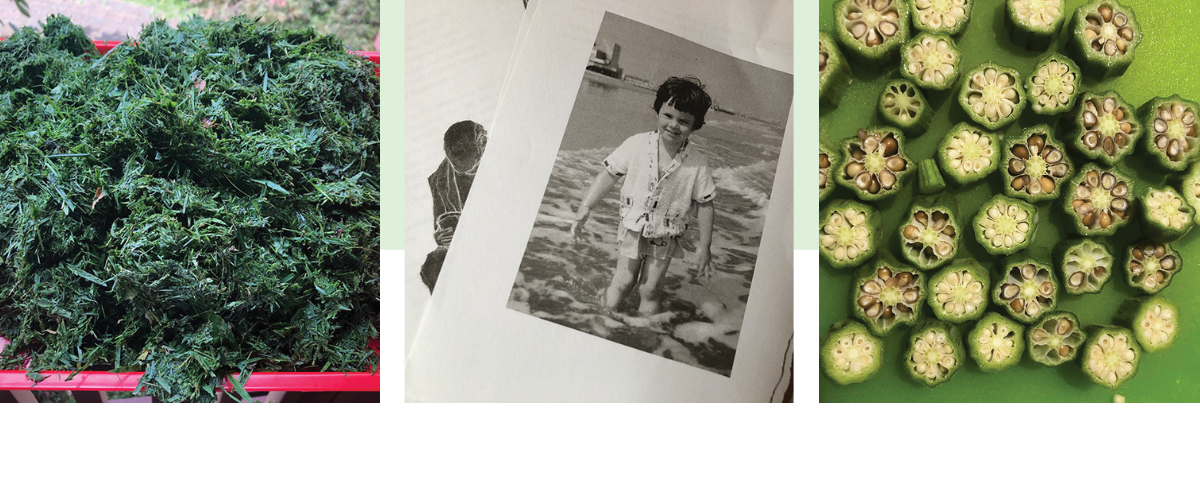

I shred copies of books that I have written, especially copies of books that contain printer errors, as my memoir-in-essays, Wife | Daughter | Self, did. But anything no one will read again will do.

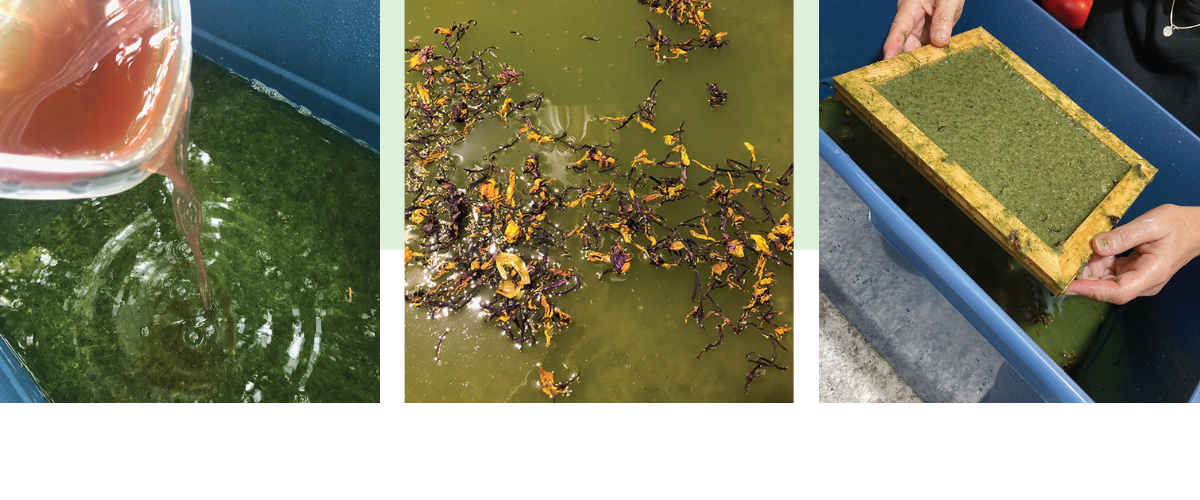

3. Slice and boil okra. The resulting juice is an interesting sticky pink concoction that serves as a formation aid. Discard the okra and set the okra juice aside.

If you want to fancy up your paper, gather nontoxic flowers (always check) and blanch them by adding them to boiling water for one minute or so, then dumping them into cold water. Asters, pansies, calendula, bee balm and marigolds are a good place to start. Set the blanched flowers aside.

4. Dissolve washing soda (sodium carbonate) in warm water (about 1 tablespoon per quart of water). Those with a separate basement/ cooking area will want to boil the substance in a non- aluminum pot. (My little house has no such space, and washing soda in the kitchen is not my idea of safe, so I adjust accordingly.)

Also, and importantly, you can make paper without washing soda. Just let your fibers soak for many days, to ensure that they are sufficiently soft.

5. Place your grass fibers and your shredded paper in a big plastic tub and cover it with the washing soda water plus any additional water you need to cover the material. Let this tub sit for at least overnight, stirring occasionally with a wooden spoon you will not be returning to the kitchen.

6. Strain the paper solution, rinsing it clean. If you have used the washing soda, best to strain several times. Collect all the excess liquid in a bucket and neutralize it with a quart or two of distilled white vinegar before disposing of it. Now collect the pulp, squeeze excess liquid from it and beat it with an old stick. You are loosening the fibers.

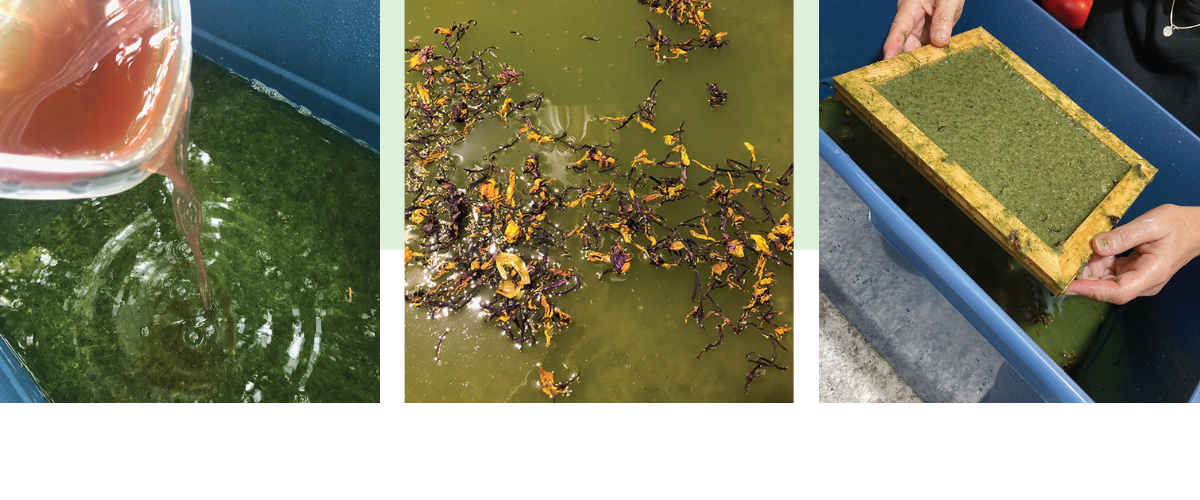

7. Now, using an old blender, add water to the purified grass-shredded paper mix and, cup by cup, blend. Pour your blended pulp into your rinsed-clean plastic-tub vat. Work until all of your fibers have been blended. Add your okra juice to the vat when you are done.

8. You now have slurry. At this point, you can add your blanched flowers (wet or dry) to the slurry. (You could alternatively add the flowers to the molded paper later.)

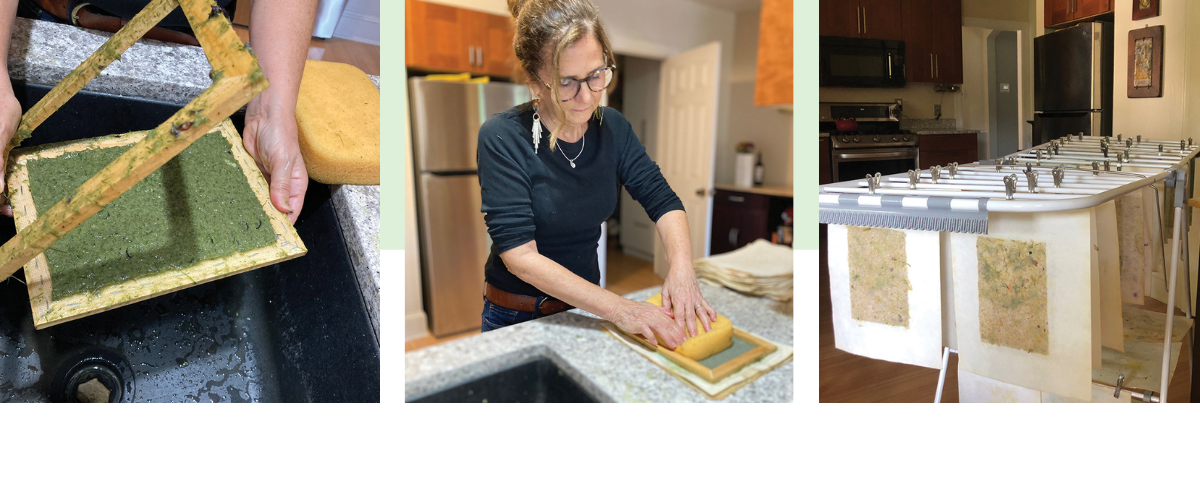

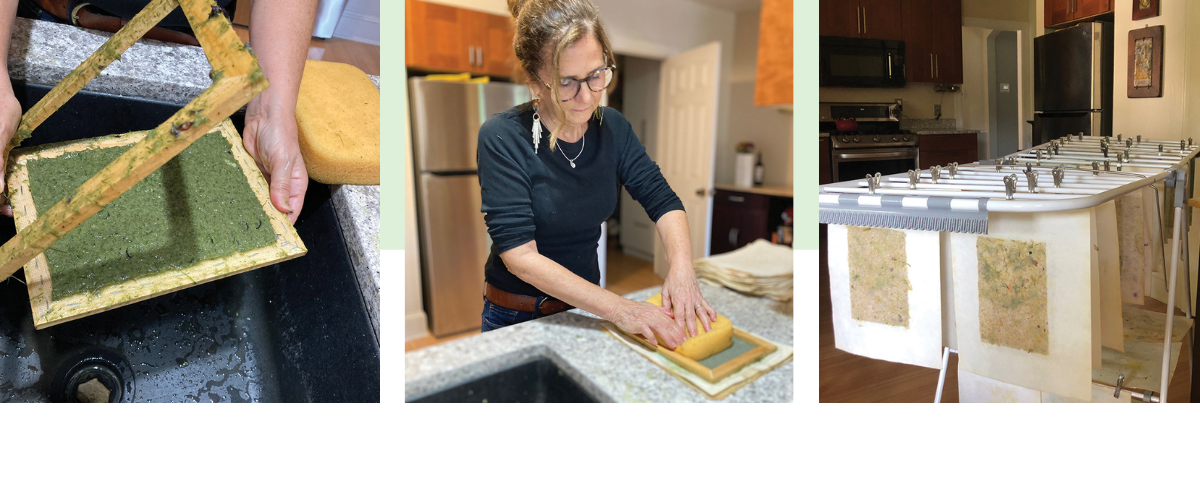

9. With your mold and deckle on hand, stir up the slurry in the vat so that the loosened fibers are suspended. Dip your mold and deckle into the slurry at an angle, collecting the slurry, then hold your mold and deckle in the liquid horizontally, gently moving the apparatus until the slurry settles.

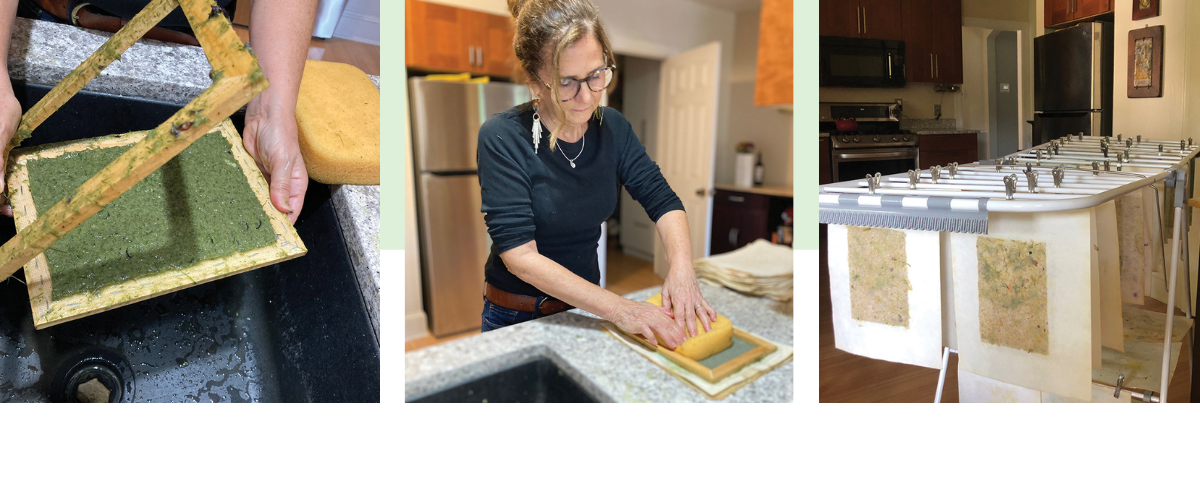

10. Lift the mold and deckle from the water (maintaining its horizontal position) and let the excess water drain. Remove the deckle. Onto old cotton T-shirts or actual couch sheets (available for purchase online), flip the mold upside down, so that the newly forming paper sheet is touching the drying surface. Then press a sponge to the back of the mold to absorb as much excess liquid as you can. Carefully remove the mold.

11. Place another cotton cloth or couch sheet on top of this new piece of paper and begin again, forming paper until you have a nice stack.

12. When you are finished pulling all your sheets, leave them beneath a heavy slab (I use marble) and let them sit for a few hours. Then clip each couch sheet to a drying rack so that the paper will dry. Later, you’ll be able to peel each piece of paper from its couching sheet. I like to press the dry paper between boards to help make them flat.

I use my paper to write on, as endpapers for my handmade books and as cover art. Here are some images of books I’ve made with all kinds of handmade paper (not just grass paper), in the studio where I make them. I’ve also used my handmade paper as a quilt of sorts, to decorate my studio.

My husband doesn’t believe in lawns. He’d be happier, he says, with pebbles.

Not willing to exchange green and buds for dusty stones, I’ve done all the green things throughout our marriage. Planted the bushes and seeds, tended the bulbs, paid the kids with the lawn mowers, gone out just after dawn or just before dusk and watered the unquenched, slapping all the while at the bugs that swarm around my head. We live on a small plot of land that was once part of a golf course that belonged to a country sprawl of a hotel, one of the finest hotels there ever was, more than a century ago.

Oh, if the elite could see us now.

But last year the kid with the lawnmower committed some fire-able offenses (like driving his machine repeatedly into our house and rattling the stucco; like running over and through the garden I’d been tending), and so I fired him. After that, there was no one willing to do the mowing for a plot of land as small and unremunerative as ours, and so all lawn maintenance came to a halt.

Our grass grew knee high.

I lived in shame. Finally, humiliation and adrenaline got the better of me. I snapped off the evening news, hiked through the green wilderness and cried big tears as I stood before our nearest, lawn-attentive neighbor.

“Please can we borrow your mower,” I said. Begged, might be the word.

Three weeks later, our borrowing days done, our own lawn mower arrived. And that’s how my husband became, at last, an actual one-yard lawn-maintenance guy.

Our economy mower is the kind you push, not the kind you ride. It’s the kind most people would stow in a garage, except we have no garage. It’s battery operated, no gas. All of this, my husband has taken in stride. Once a week during the height of grass-growing season, you can find him at an early hour, making pretty mowing patterns.

Several weeks ago, my husband, after announcing a return to “Best in Neighborhood” status, also announced this: “I left all the cut grass in a pile by the trash can, in case you want to do something with it.”

“Do something with it?” I repeated, tilting the end of my sentence with a question-mark sound. Then I remembered something I’d mentioned casually long ago: “Someday,” I’d declared, “I’ll make grass paper.”

Grass paper already exists, of course. This was not some grand, original notion of mine. Like the leaves of irises and yucca plants or the skins of onions or the stalks of cattails (minus the cigars), grass is a wonderful paper-making material. A miracle of cellulose, chlorophyll and water, grass is fibrous.

When you cut it up and drop it (carefully) in a non-aluminum pot of washing-soda-enhanced water, you have before you the start of something — fibers breaking away from fibers so that they may come together again as paper. Accelerate the process by rinsing the macerated grass and pouring it into a blender. Then ball the strained blendered stuff up and place it on a sturdy surface. Find a pair of wide wooden sticks.

Pound. Pretend you are playing the drums. What you’re doing is very noble. You are freeing fibers.

I had some smelly fun with this.

I did the work outside, so as not to contaminate my kitchen. I got my husband involved with the makeshift apparatus, the straining, the drumming. The mosquitoes arrived uninvited. Once my grass fibers were as free as they were ever going to be, I dumped them into a vat of clean water, threw in some shredded paper, tossed in some okra juice (I’d boiled sliced okra and saved the slime; the slime is a formation aid), and stirred the whole thing up with my hand. Then I grabbed my little mold and deckle. I dipped. I gently shook. I let the water drain.

There, on the face of my mold was the start of a piece of paper — by which I mean beaten and soaked grass fibers attaching to beaten and soaked grass fibers. Of course, the thin wet sheet would have to be removed from the mold, layered between old cotton T-shirts and dried (along with other sheets) beneath a slab of marble. Of course, this drying thing would test my patience. But at the end of it all, a few days later, I had myself something I had not had before, made of grass that always knew, in its green heart, that it was anything but trash.

A Step-by-Step Guide to the Making of Grass Paper

(Materials and tools indicated in bold print)

1. Collect the mowed grass. Four healthy-sized handfuls should do the trick. Gratitude toward the lawn mower helps to ensure future supplies.

2. Shred some existing paper. I find that this gives the paper you are making more strength and character.

I shred copies of books that I have written, especially copies of books that contain printer errors, as my memoir-in-essays, Wife | Daughter | Self, did. But anything no one will read again will do.

3. Slice and boil okra. The resulting juice is an interesting sticky pink concoction that serves as a formation aid. Discard the okra and set the okra juice aside.

If you want to fancy up your paper, gather nontoxic flowers (always check) and blanch them by adding them to boiling water for one minute or so, then dumping them into cold water. Asters, pansies, calendula, bee balm and marigolds are a good place to start. Set the blanched flowers aside.

4. Dissolve washing soda (sodium carbonate) in warm water (about 1 tablespoon per quart of water). Those with a separate basement/ cooking area will want to boil the substance in a non- aluminum pot. (My little house has no such space, and washing soda in the kitchen is not my idea of safe, so I adjust accordingly.)

Also, and importantly, you can make paper without washing soda. Just let your fibers soak for many days, to ensure that they are sufficiently soft.

5. Place your grass fibers and your shredded paper in a big plastic tub and cover it with the washing soda water plus any additional water you need to cover the material. Let this tub sit for at least overnight, stirring occasionally with a wooden spoon you will not be returning to the kitchen.

6. Strain the paper solution, rinsing it clean. If you have used the washing soda, best to strain several times. Collect all the excess liquid in a bucket and neutralize it with a quart or two of distilled white vinegar before disposing of it. Now collect the pulp, squeeze excess liquid from it and beat it with an old stick. You are loosening the fibers.

7. Now, using an old blender, add water to the purified grass-shredded paper mix and, cup by cup, blend. Pour your blended pulp into your rinsed-clean plastic-tub vat. Work until all of your fibers have been blended. Add your okra juice to the vat when you are done.

8. You now have slurry. At this point, you can add your blanched flowers (wet or dry) to the slurry. (You could alternatively add the flowers to the molded paper later.)

9. With your mold and deckle on hand, stir up the slurry in the vat so that the loosened fibers are suspended. Dip your mold and deckle into the slurry at an angle, collecting the slurry, then hold your mold and deckle in the liquid horizontally, gently moving the apparatus until the slurry settles.

10. Lift the mold and deckle from the water (maintaining its horizontal position) and let the excess water drain. Remove the deckle. Onto old cotton T-shirts or actual couch sheets (available for purchase online), flip the mold upside down, so that the newly forming paper sheet is touching the drying surface. Then press a sponge to the back of the mold to absorb as much excess liquid as you can. Carefully remove the mold.

11. Place another cotton cloth or couch sheet on top of this new piece of paper and begin again, forming paper until you have a nice stack.

12. When you are finished pulling all your sheets, leave them beneath a heavy slab (I use marble) and let them sit for a few hours. Then clip each couch sheet to a drying rack so that the paper will dry. Later, you’ll be able to peel each piece of paper from its couching sheet. I like to press the dry paper between boards to help make them flat.

I use my paper to write on, as endpapers for my handmade books and as cover art. Here are some images of books I’ve made with all kinds of handmade paper (not just grass paper), in the studio where I make them. I’ve also used my handmade paper as a quilt of sorts, to decorate my studio.