I’ll never forget the day I decided, on a whim, to show a professor one of my upcycled book designs.

I was in my mid-40s at the time, plunging headfirst into the world of book arts at our local university. With a decade of full-time parenting behind me, I was no longer interested in pursuing a traditional career in academia or journalism — as I had before my sons were born. At long last, I was allowing my creative inclinations to lead the way.

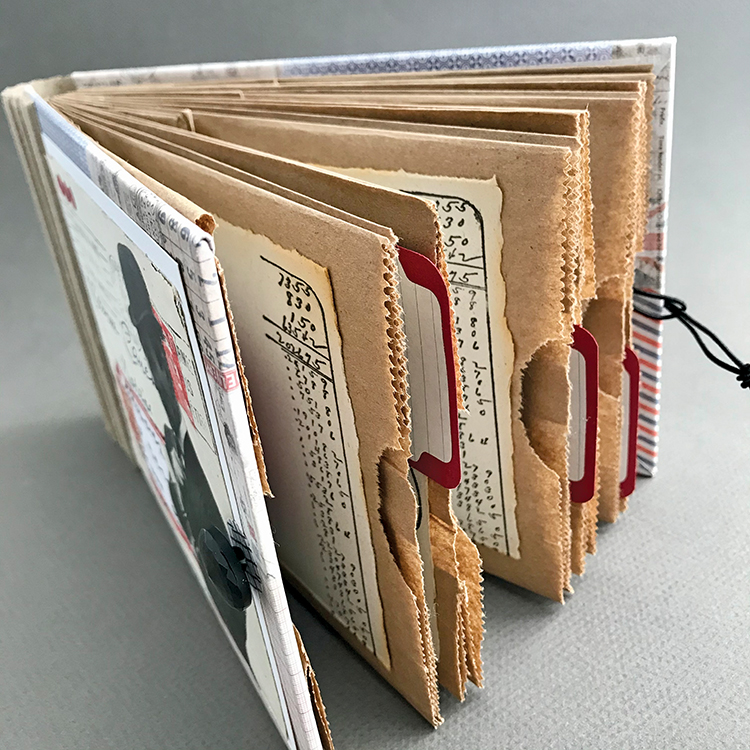

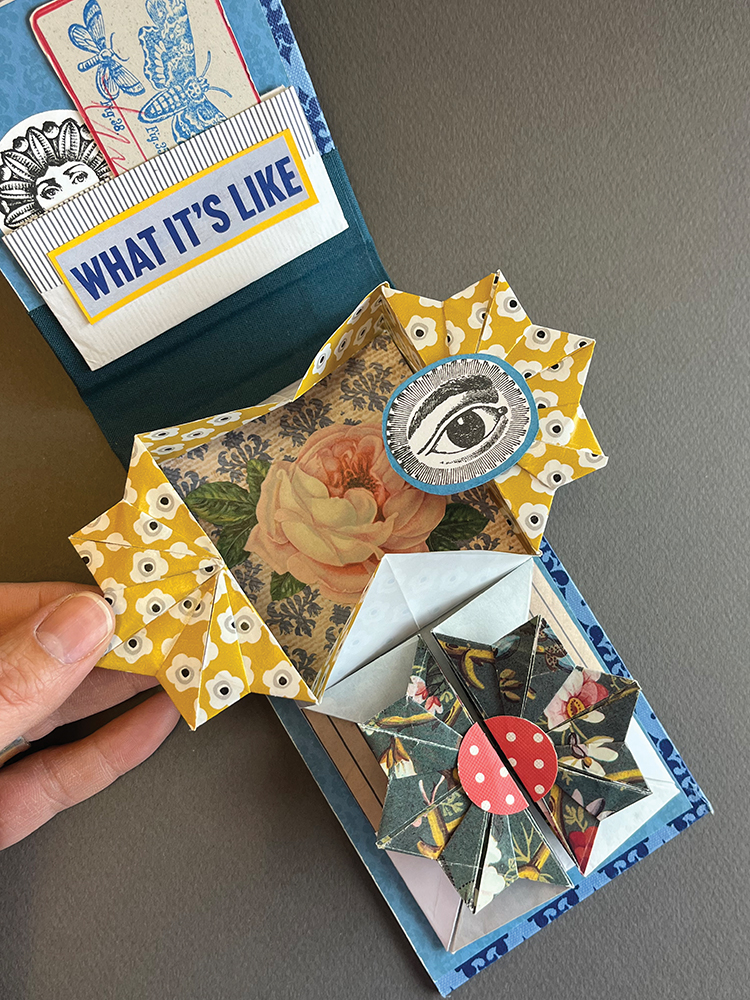

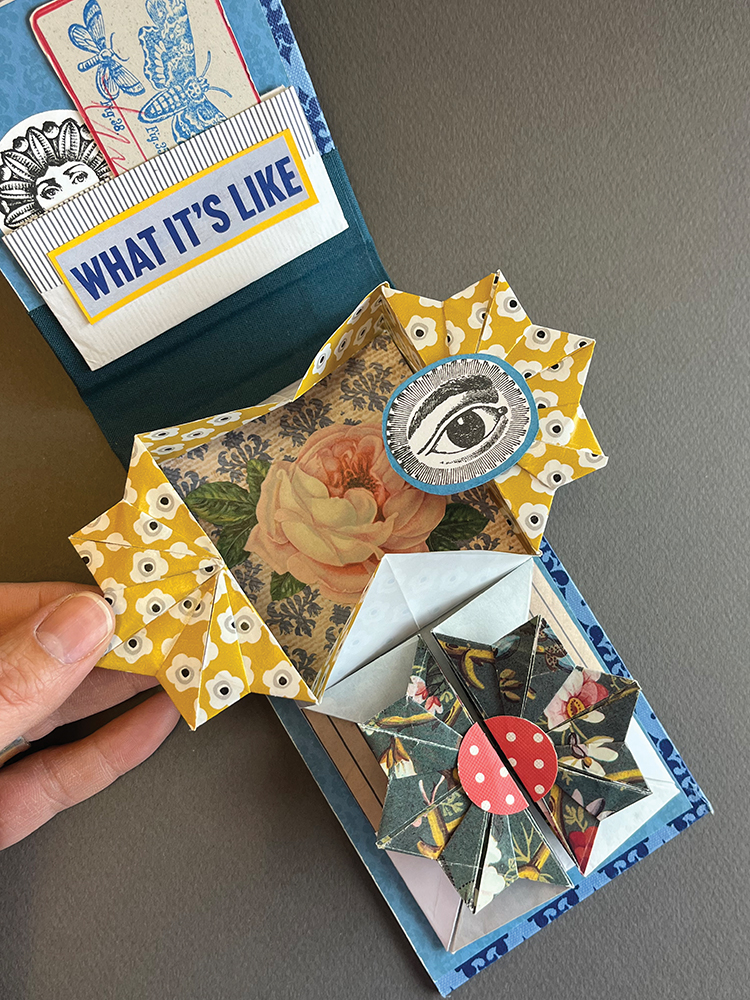

The little book I pulled from my backpack that afternoon was a simple affair: a scrappy patchwork of envelopes, thread and double-sided tape. The envelope pages doubled as pockets, and I’d decorated the cover with a collage of paper ephemera.

I’m not sure what I expected. Perhaps a critique on my assembly, or maybe design suggestions. Probably a raised eyebrow at my unconventional materials.

To my surprise, she wanted to buy it.

I remember utter disbelief quickly giving way to pride, and then … something else. If I had to pinpoint the moment when I began to see myself as a book artist, this was it. People, I suddenly realized, would pay me to do this. Maybe not all people, but some. Feigning nonchalance as we settled on a price, I left class with $12 (!) secured within the pages of my notebook.

My head was spinning! My scrappy book lacked all the solemnity of the fancy books people paid for. I hadn’t crafted an heirloom-quality, leather-bound, gold-leafed tome (which, incidentally, I had no interest in making), I’d simply taken paper most people throw away and re-imagined it as a book.

Weeks passed while I swirled this new experience around in my mind, and I watched it solidify into a novel idea. My fear that I was wasting my time making books was now joined by another thought: Maybe I was an artist building a body of work! Just maybe, I was forging a new life path. I granted myself full permission to indulge in bookmaking, and stopped wondering whether I should be doing something else.

Not long after, another instructor, my friend Jaime Lynn Shafer, approached with an intriguing proposition. She couldn’t endure the commute to a nearby town where she led basic bookbinding workshops. Would I be willing to take over the post?

Internal objections flooded in — I’m just a student, I thought. But more than that, I couldn’t understand why Jaime — who was well aware of my unconventional approach — believed I should be the one ushering new bookbinders into the fold.

“What could I possibly teach?” I asked. She didn’t hesitate: The upcycled envelope book I’d recently created (and sold) would be the perfect introductory class, she said. Contemplating the thrill I’d felt transforming household paper into a handmade book, I couldn’t pass up the chance to share.

I wish I could say that at that point, I strolled away into my happily-ever-after of teaching success.

Nope. The truth is: I got off to a really rough start.

Introducing myself as a book arts teacher to my first class was painfully awkward. I didn’t have years of experience as a bookbinder, much less experience as a bookbinding teacher. I resolved to shelve my reservations and plunged in with enthusiasm. To my surprise, I experienced modest success, but only at first. After a few successful classes, interest seemed to wane and I struggled to fill my workshops. I remember spending hours preparing a class, only to have it canceled for failing to meet the required minimum of five students.

After six months, bruised and discouraged, I decided to take a teaching hiatus. Over the next year and a half, just one thing kept me on my creative path — my unwavering love for upcycled books. I just couldn’t stop making them. I directed the full force of my creativity at bookmaking, and every time I came up with a new design, I fantasized about sharing it with a group of students.

Then, one day, something totally unexpected happened.

Another friend, Katherine Case (who taught the very first book arts class I ever took) decided to step down as a bookbinding instructor at the Nevada Museum of Art. Katherine encouraged me to apply as her replacement, and even introduced me to the director of the museum school.

Katherine’s endorsement worked, and I was thrilled to be welcomed as a new teacher. After my first class sold out (the scrappy envelope book class, incidentally), the same low-enrollment problem resurfaced. But nonetheless, something was different this time — I didn’t give up. It helped that Katherine confided that she, too, struggled to fill classes sometimes.

I kept pitching fresh ideas, and also opened an Etsy shop to sell my work online. By the time we left Nevada in 2019, I had sold dozens of handmade books and assembled a loyal group of book arts students who returned class after class.

Buoyed by this success, I set out for our new home in Northern Virginia with high hopes of finding scores of eager new students. As you may have already guessed, fate had something else in mind for me — along with everyone else. Just a few months into our move, the coronavirus pandemic sent the whole world indoors and my first in-person class was canceled, along with scores of other events worldwide.

I also had another challenge. My Etsy shop had started to sell out regularly, but the task of keeping it stocked was taking a toll on my hands, leaving me with overuse injuries. I was suddenly facing a bewildering new reality: If I wanted to continue being a working artist, my best path forward was the world of online instruction. Which meant I had to strike out into the unknown, once again, feeling unskilled and unprepared just like when I started. My task: to decipher the new world of virtual learning — the wait rooms, the chats, the gallery-vs-speaker view — and become an online book arts teacher.

The adjustment was challenging, at first. For starters, I could no longer physically inspect my students’ work when their projects went astray. But what technology took away in terms of proximity, it has generously compensated with an extended reach. Virtual instruction expanded the walls of my classroom, welcoming students from all over the globe, including Australia, Thailand, Italy, Canada and New Zealand.

I was hired to teach online classes for Creativebug, a subscription-based arts instruction platform, and created a class for Skillshare, another hub of online learning. In the process, I learned how to film and edit my own videos. I now teach online classes almost exclusively, using both Zoom and prerecorded video formats.

My first independent online class, Upcycled Bookbinding 101, launched last year, drawing over 180 students to date. In addition to book arts, I teach my second passion, upcycled mail art — or the art of creating artful correspondence with salvaged paper.

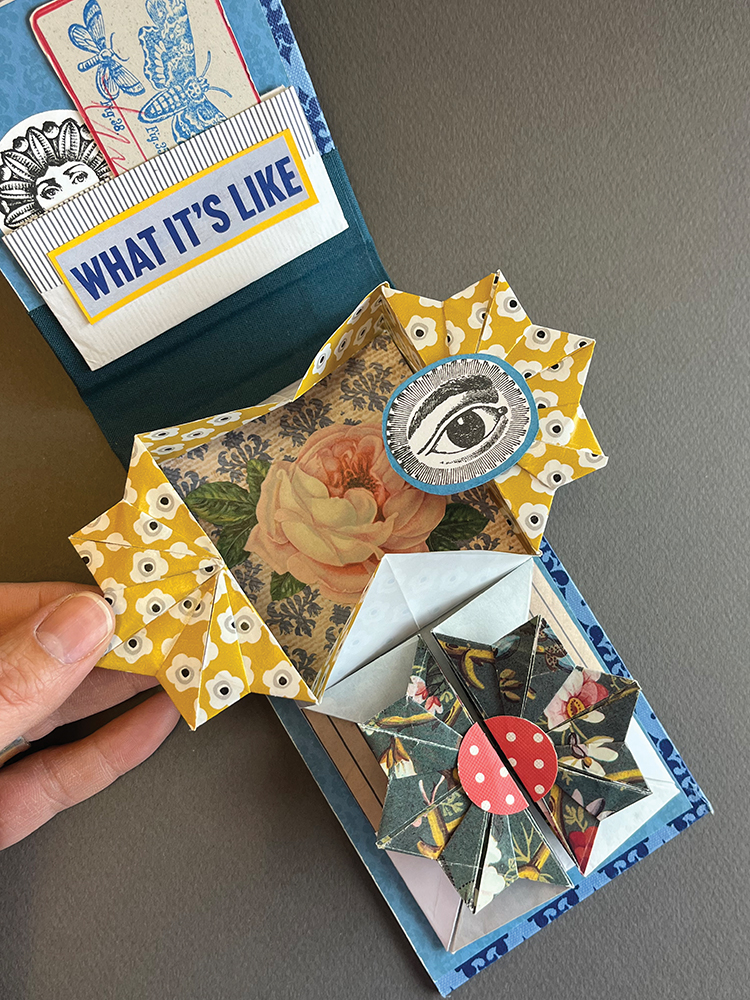

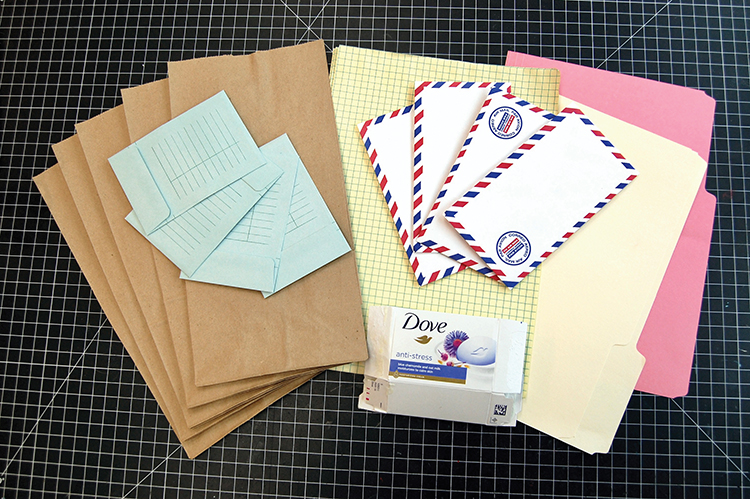

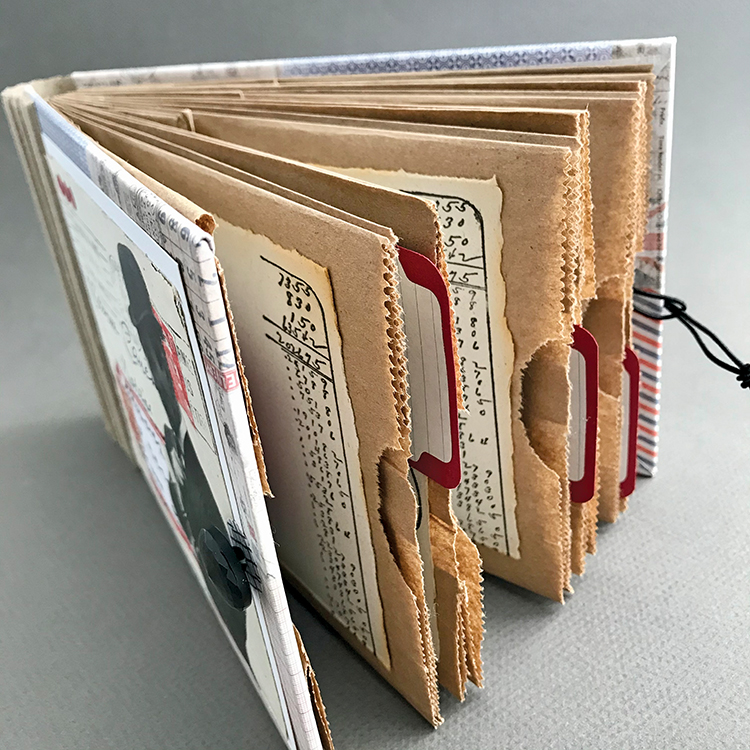

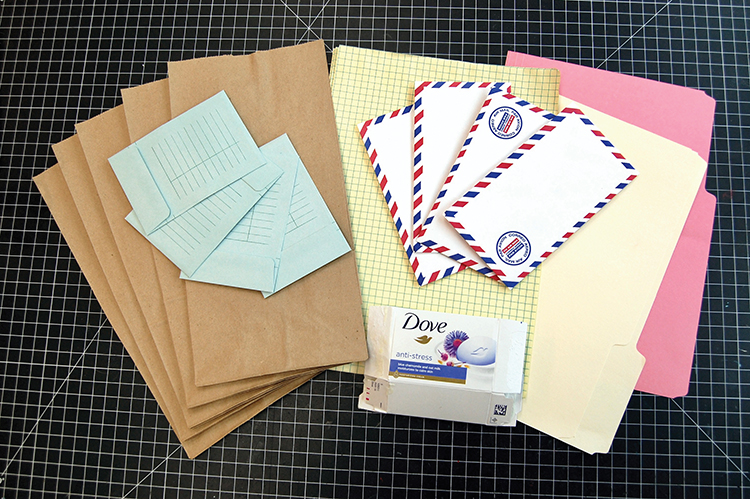

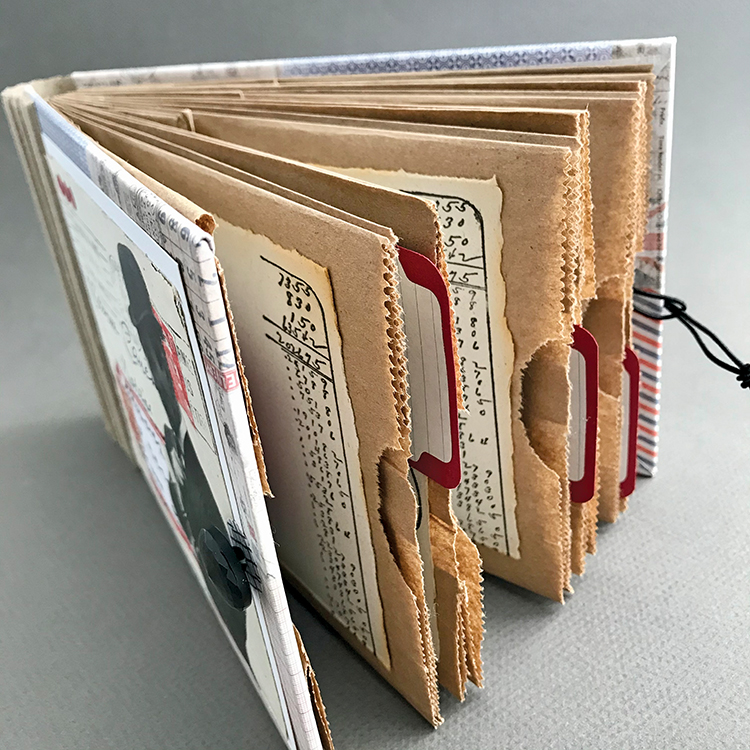

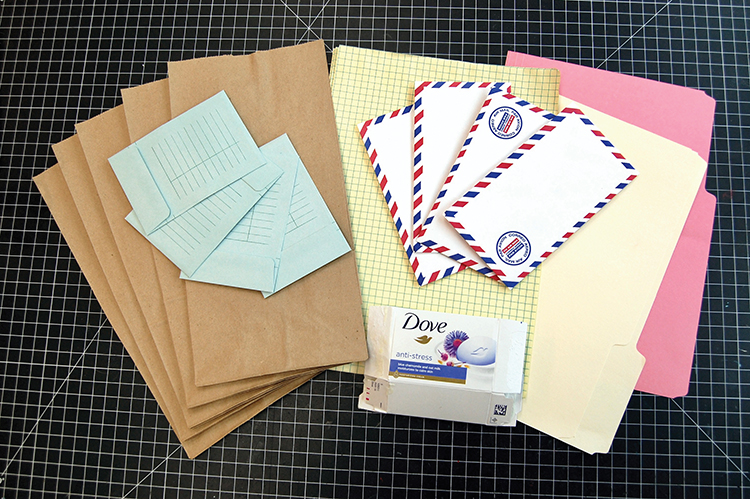

What I love most about upcycled bookbinding is how it turns the creative process on its head, forcing the bookmaker to summon all their imaginative powers. Unlike traditional bookbinding, where you start with an idea, gather materials and follow a set of instructions, upcycled bookbinding yanks away the security of steps and sends you out into the paper wilds. You start with whatever you have — envelopes, file folders, cardboard boxes — and let it guide the way. I call it “speaking the language of paper.”

Turns out, many manufactured paper products are particularly well suited for bookmaking if you know how to “read” them. I’ve organized an entire class around this philosophy, and the list of suitable paper items is long. (I have a free guide available on my website showcasing 17 different household paper items you can incorporate into books.)

Now when I consider whether a certain paper item can become a book, I ask a series of questions: Does its form match the natural structure of a book? Is the paper better suited for covers or pages? Is it beautiful, or will it need enhancing?

If I had to choose just one paper item for bookmaking, it would be the humble envelope. Envelopes are not only well suited for covers, they are also well suited for pages, and they happen to boast one of household paper’s most functional features: pockets.

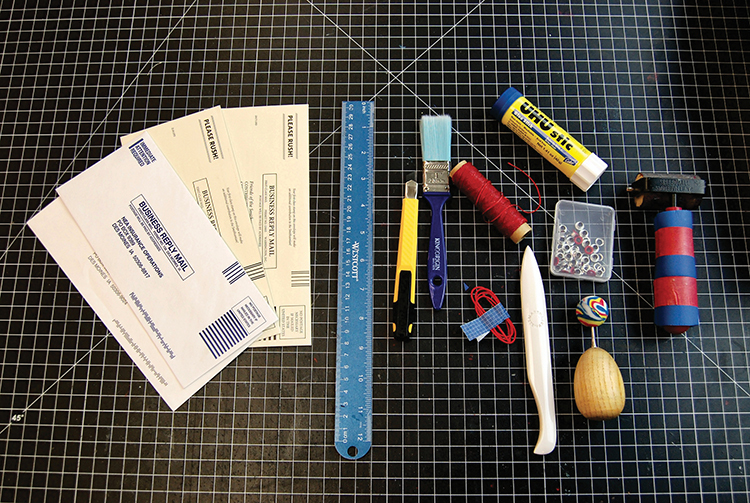

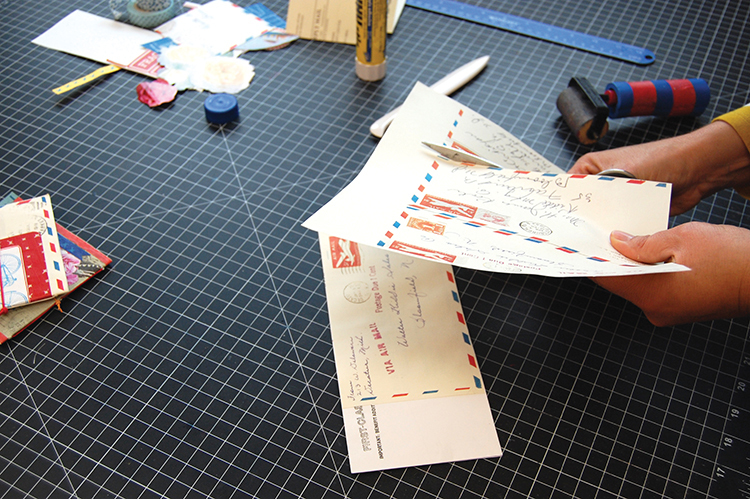

I used four business reply to create the scrappy envelope book I sold to my professor. Yes, I mean the pre-addressed envelopes that businesses send in hopes you’ll return them with money inside.

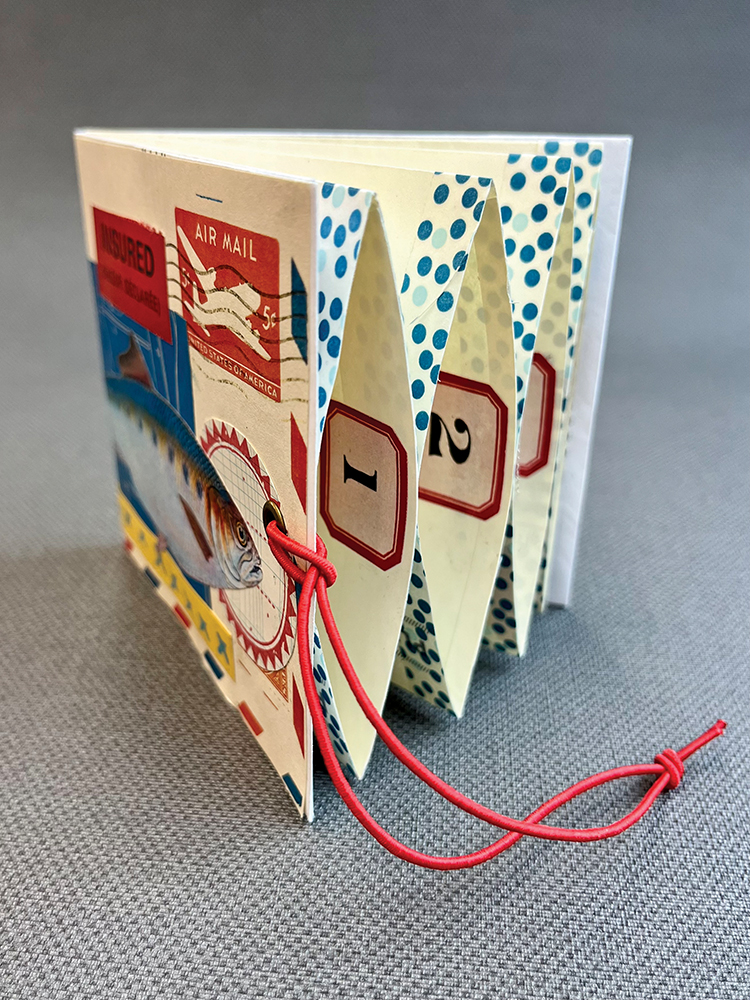

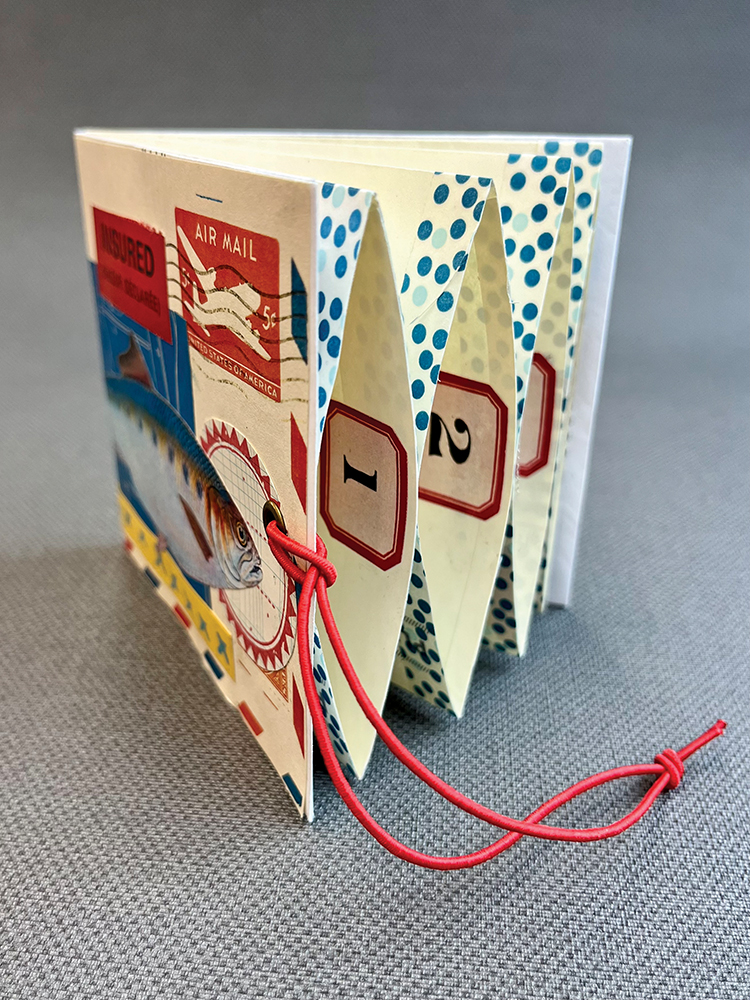

Since book covers are generally thicker than book pages, I fortify the cover of this envelope book by gluing one of the envelopes to a second envelope, back-to-back.

The other two envelopes will now become the pages. After sealing the flaps, I fold them in half width-wise to create a page section called a “signature.”

You might be wondering how my pages will have pockets if I start by sealing the envelope flaps. But part of the fun of upcycling is subverting the original design of an object and finding a way to make it work in a new form. So, the next step is slicing off the short front edges of the envelope-pages. By trimming the short ends of the sealed envelopes, I create new pockets that are narrow and deep, rather than shallow and wide.

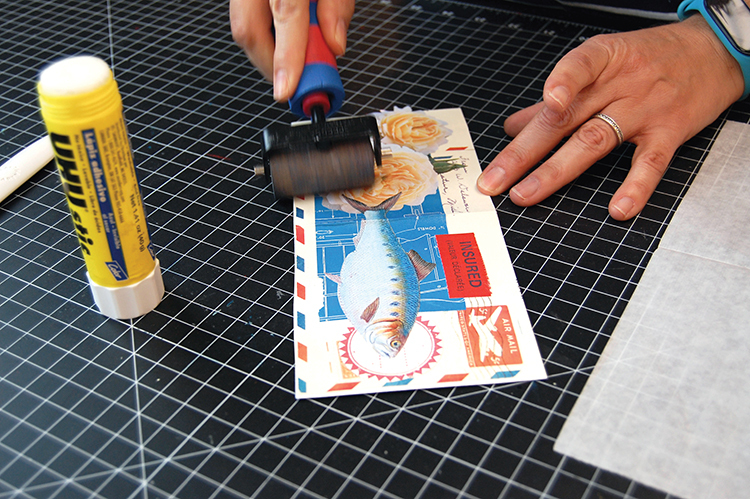

Once the pages and cover are ready, I move on to one of the most important processes of upcycled bookbinding: embellishment. Ordinary papers like envelopes usually require a little artistry, something to confer polish and style. To elevate the cover of this book visually, I collage the front and back. Often, I use scanned images of vintage papers, like old used envelopes, because aged paper is often fragile and difficult to work with. I use glue stick to attach my collage papers, and a small brayer to smooth them out.

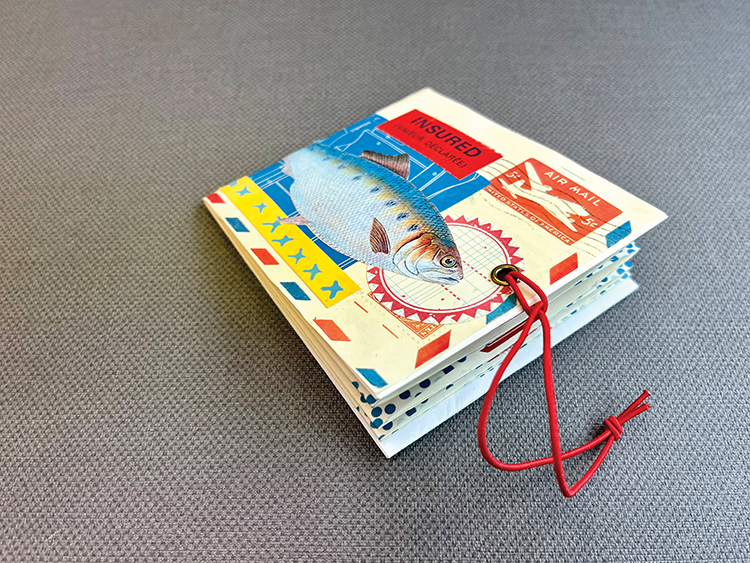

When the cover is collaged, it’s time to embellish the pages. A ring of washi tape wrapped around the openings of the pockets adds polish and strengthens the raw, trimmed edges. Next, I join the cover and pages with a simple bookbinding technique: the three-hole pamphlet stitch.

Although my structure now resembles an actual book, complete with cover and pages, I’m still not finished! I’ve only just arrived at the magical step that transforms this structure from so-so to spectacular. Using a strip of double-sided tape that runs horizontally across the center of the pages, I connect the pages to the cover, and the pages to each other. Now, the book is transformed from a book with pocketed pages to a book of pockets. Every time I open the cover, the pockets gape open allowing items to be easily added or removed. The book is now ready for the last two details: A metal eyelet and elastic cord to help keep the pockets secure, and numbered labels inside the pockets for a bit of extra style.

Seven years after this little book launched my career as a book arts teacher, it’s still one of my most popular classes. Nevertheless, other things have changed drastically over the years — namely, my own confidence. I’ve finally found my voice as an enthusiastic advocate for upcycled bookbinding, and I no longer make excuses for my unusual methods. In fact, I sing their praises!

There is so much joy in taking an item that was meant to be thrown away and reimagining it as something permanent and beautiful. The way I see it, making beautiful books out of fancy paper is somewhat expected; but making beautiful books out of ordinary paper is nothing short of magic.

Aspiring or experienced bookbinders interested in beginning their upcycled bookmaking journey with me can find links to my online classes, and also download my free bookbinding tool list, on my website.

I look forward to meeting you in a future class!

I’ll never forget the day I decided, on a whim, to show a professor one of my upcycled book designs.

I was in my mid-40s at the time, plunging headfirst into the world of book arts at our local university. With a decade of full-time parenting behind me, I was no longer interested in pursuing a traditional career in academia or journalism — as I had before my sons were born. At long last, I was allowing my creative inclinations to lead the way.

The little book I pulled from my backpack that afternoon was a simple affair: a scrappy patchwork of envelopes, thread and double-sided tape. The envelope pages doubled as pockets, and I’d decorated the cover with a collage of paper ephemera.

I’m not sure what I expected. Perhaps a critique on my assembly, or maybe design suggestions. Probably a raised eyebrow at my unconventional materials.

To my surprise, she wanted to buy it.

I remember utter disbelief quickly giving way to pride, and then … something else. If I had to pinpoint the moment when I began to see myself as a book artist, this was it. People, I suddenly realized, would pay me to do this. Maybe not all people, but some. Feigning nonchalance as we settled on a price, I left class with $12 (!) secured within the pages of my notebook.

My head was spinning! My scrappy book lacked all the solemnity of the fancy books people paid for. I hadn’t crafted an heirloom-quality, leather-bound, gold-leafed tome (which, incidentally, I had no interest in making), I’d simply taken paper most people throw away and re-imagined it as a book.

Weeks passed while I swirled this new experience around in my mind, and I watched it solidify into a novel idea. My fear that I was wasting my time making books was now joined by another thought: Maybe I was an artist building a body of work! Just maybe, I was forging a new life path. I granted myself full permission to indulge in bookmaking, and stopped wondering whether I should be doing something else.

Not long after, another instructor, my friend Jaime Lynn Shafer, approached with an intriguing proposition. She couldn’t endure the commute to a nearby town where she led basic bookbinding workshops. Would I be willing to take over the post?

Internal objections flooded in — I’m just a student, I thought. But more than that, I couldn’t understand why Jaime — who was well aware of my unconventional approach — believed I should be the one ushering new bookbinders into the fold.

“What could I possibly teach?” I asked. She didn’t hesitate: The upcycled envelope book I’d recently created (and sold) would be the perfect introductory class, she said. Contemplating the thrill I’d felt transforming household paper into a handmade book, I couldn’t pass up the chance to share.

I wish I could say that at that point, I strolled away into my happily-ever-after of teaching success.

Nope. The truth is: I got off to a really rough start.

Introducing myself as a book arts teacher to my first class was painfully awkward. I didn’t have years of experience as a bookbinder, much less experience as a bookbinding teacher. I resolved to shelve my reservations and plunged in with enthusiasm. To my surprise, I experienced modest success, but only at first. After a few successful classes, interest seemed to wane and I struggled to fill my workshops. I remember spending hours preparing a class, only to have it canceled for failing to meet the required minimum of five students.

After six months, bruised and discouraged, I decided to take a teaching hiatus. Over the next year and a half, just one thing kept me on my creative path — my unwavering love for upcycled books. I just couldn’t stop making them. I directed the full force of my creativity at bookmaking, and every time I came up with a new design, I fantasized about sharing it with a group of students.

Then, one day, something totally unexpected happened.

Another friend, Katherine Case (who taught the very first book arts class I ever took) decided to step down as a bookbinding instructor at the Nevada Museum of Art. Katherine encouraged me to apply as her replacement, and even introduced me to the director of the museum school.

Katherine’s endorsement worked, and I was thrilled to be welcomed as a new teacher. After my first class sold out (the scrappy envelope book class, incidentally), the same low-enrollment problem resurfaced. But nonetheless, something was different this time — I didn’t give up. It helped that Katherine confided that she, too, struggled to fill classes sometimes.

I kept pitching fresh ideas, and also opened an Etsy shop to sell my work online. By the time we left Nevada in 2019, I had sold dozens of handmade books and assembled a loyal group of book arts students who returned class after class.

Buoyed by this success, I set out for our new home in Northern Virginia with high hopes of finding scores of eager new students. As you may have already guessed, fate had something else in mind for me — along with everyone else. Just a few months into our move, the coronavirus pandemic sent the whole world indoors and my first in-person class was canceled, along with scores of other events worldwide.

I also had another challenge. My Etsy shop had started to sell out regularly, but the task of keeping it stocked was taking a toll on my hands, leaving me with overuse injuries. I was suddenly facing a bewildering new reality: If I wanted to continue being a working artist, my best path forward was the world of online instruction. Which meant I had to strike out into the unknown, once again, feeling unskilled and unprepared just like when I started. My task: to decipher the new world of virtual learning — the wait rooms, the chats, the gallery-vs-speaker view — and become an online book arts teacher.

The adjustment was challenging, at first. For starters, I could no longer physically inspect my students’ work when their projects went astray. But what technology took away in terms of proximity, it has generously compensated with an extended reach. Virtual instruction expanded the walls of my classroom, welcoming students from all over the globe, including Australia, Thailand, Italy, Canada and New Zealand.

I was hired to teach online classes for Creativebug, a subscription-based arts instruction platform, and created a class for Skillshare, another hub of online learning. In the process, I learned how to film and edit my own videos. I now teach online classes almost exclusively, using both Zoom and prerecorded video formats.

My first independent online class, Upcycled Bookbinding 101, launched last year, drawing over 180 students to date. In addition to book arts, I teach my second passion, upcycled mail art — or the art of creating artful correspondence with salvaged paper.

What I love most about upcycled bookbinding is how it turns the creative process on its head, forcing the bookmaker to summon all their imaginative powers. Unlike traditional bookbinding, where you start with an idea, gather materials and follow a set of instructions, upcycled bookbinding yanks away the security of steps and sends you out into the paper wilds. You start with whatever you have — envelopes, file folders, cardboard boxes — and let it guide the way. I call it “speaking the language of paper.”

Turns out, many manufactured paper products are particularly well suited for bookmaking if you know how to “read” them. I’ve organized an entire class around this philosophy, and the list of suitable paper items is long. (I have a free guide available on my website showcasing 17 different household paper items you can incorporate into books.)

Now when I consider whether a certain paper item can become a book, I ask a series of questions: Does its form match the natural structure of a book? Is the paper better suited for covers or pages? Is it beautiful, or will it need enhancing?

If I had to choose just one paper item for bookmaking, it would be the humble envelope. Envelopes are not only well suited for covers, they are also well suited for pages, and they happen to boast one of household paper’s most functional features: pockets.

I used four business reply to create the scrappy envelope book I sold to my professor. Yes, I mean the pre-addressed envelopes that businesses send in hopes you’ll return them with money inside.

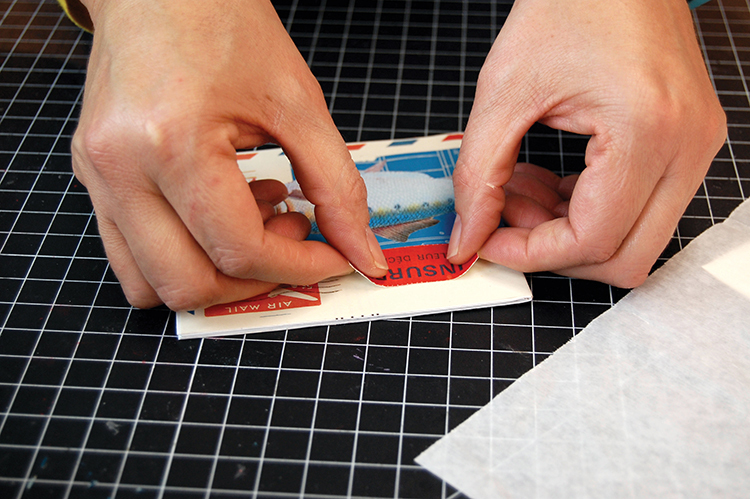

Since book covers are generally thicker than book pages, I fortify the cover of this envelope book by gluing one of the envelopes to a second envelope, back-to-back.

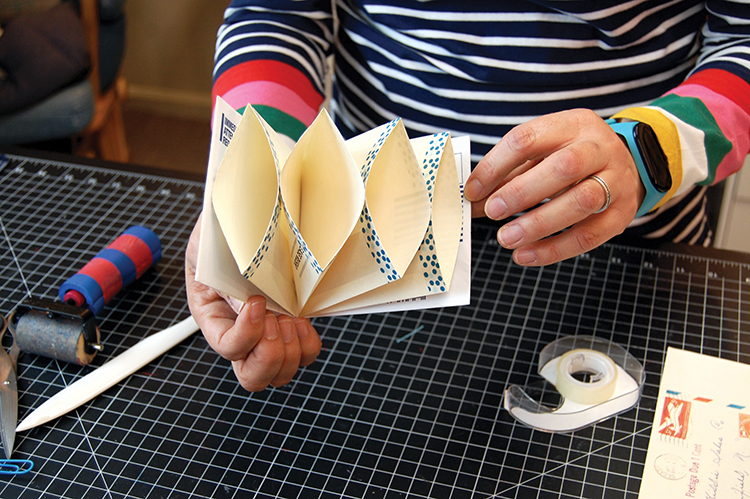

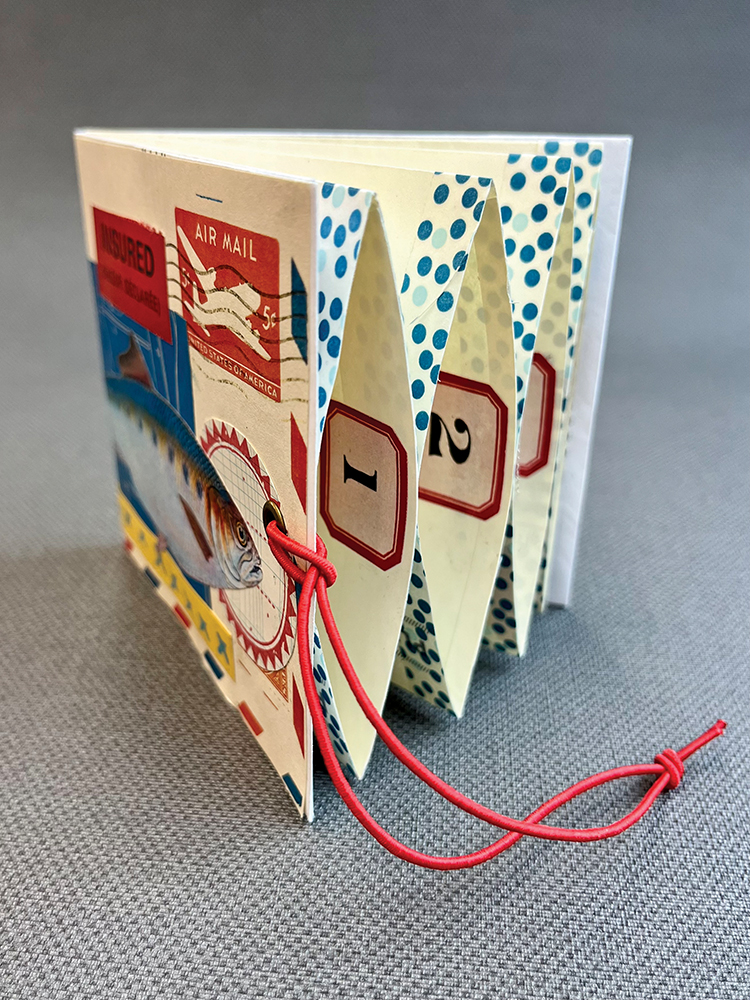

The other two envelopes will now become the pages. After sealing the flaps, I fold them in half width-wise to create a page section called a “signature.”

You might be wondering how my pages will have pockets if I start by sealing the envelope flaps. But part of the fun of upcycling is subverting the original design of an object and finding a way to make it work in a new form. So, the next step is slicing off the short front edges of the envelope-pages. By trimming the short ends of the sealed envelopes, I create new pockets that are narrow and deep, rather than shallow and wide.

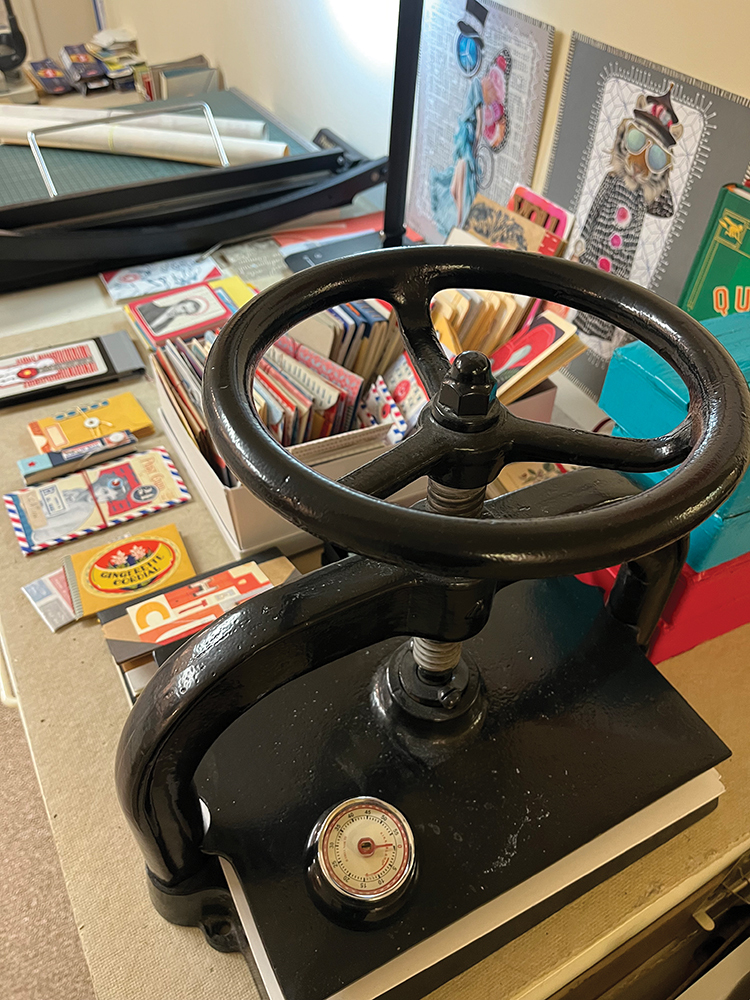

Once the pages and cover are ready, I move on to one of the most important processes of upcycled bookbinding: embellishment. Ordinary papers like envelopes usually require a little artistry, something to confer polish and style. To elevate the cover of this book visually, I collage the front and back. Often, I use scanned images of vintage papers, like old used envelopes, because aged paper is often fragile and difficult to work with. I use glue stick to attach my collage papers, and a small brayer to smooth them out.

When the cover is collaged, it’s time to embellish the pages. A ring of washi tape wrapped around the openings of the pockets adds polish and strengthens the raw, trimmed edges. Next, I join the cover and pages with a simple bookbinding technique: the three-hole pamphlet stitch.

Although my structure now resembles an actual book, complete with cover and pages, I’m still not finished! I’ve only just arrived at the magical step that transforms this structure from so-so to spectacular. Using a strip of double-sided tape that runs horizontally across the center of the pages, I connect the pages to the cover, and the pages to each other. Now, the book is transformed from a book with pocketed pages to a book of pockets. Every time I open the cover, the pockets gape open allowing items to be easily added or removed. The book is now ready for the last two details: A metal eyelet and elastic cord to help keep the pockets secure, and numbered labels inside the pockets for a bit of extra style.

Seven years after this little book launched my career as a book arts teacher, it’s still one of my most popular classes. Nevertheless, other things have changed drastically over the years — namely, my own confidence. I’ve finally found my voice as an enthusiastic advocate for upcycled bookbinding, and I no longer make excuses for my unusual methods. In fact, I sing their praises!

There is so much joy in taking an item that was meant to be thrown away and reimagining it as something permanent and beautiful. The way I see it, making beautiful books out of fancy paper is somewhat expected; but making beautiful books out of ordinary paper is nothing short of magic.

Aspiring or experienced bookbinders interested in beginning their upcycled bookmaking journey with me can find links to my online classes, and also download my free bookbinding tool list, on my website.

I look forward to meeting you in a future class!