As I gently trace a path through waist-high reeds along the riverbank, I am looking for a secluded spot where I can sit and sketch. Once I find a nicely hidden nook, I dip down and begin. Lots of my work is about what you see when you find quiet spots like this, it evokes a feeling of sitting patiently and watching nature emerge.

My prints, populated by birds, wildflowers and leaves, all start in this way, with walking out into the Cornish countryside in search of minute details to capture in initial drawings. I begin with dashes of pencil marks that catch the angle of a bird’s cocked head or the curve of its wing in flight. Later, back at my workshop, I will add in more details in ink and work those images into stylised scenes. These designs are later painstakingly carved into lino blocks and then hand-printed onto paper or linen.

The idea for the larger design tends to come together as I head home after a morning’s sketching. As I retrace my steps, it takes shape in my mind’s eye. And even that steady act of walking is all part of the creative process; if I have to get in the car afterwards and drive, it’s never quite the same—I lose my thread.

To draw, I need to be immersed in nature and to follow its slow, steady rhythms.

This love of wandering through the Cornish countryside is something I have done since childhood. My best memories are of exploring the narrow lanes and hedgerows around St Erth with my Grandpa. It wasn’t about getting somewhere; it was more of an idle dawdle. We’d carry thumb sticks to swish away stinging nettles and I’d pick little posies of wildflowers. It was all very gentle, very kind. He slowed everything down to my child’s pace.

My grandfather and I called our outings ‘hedgerow grazing’ and that habit of literally combing the foliage to seek out small creatures, buds and flowers stood me in good stead for my career as an artist. I think taking time to look really closely helped develop my eye for detail.

I grew up in Crowan, a village in Cornwall’s former mining heartland, and then the wilder coastal setting of St Just. My school reports tended to dismiss me as “lazy” or said I had “a poor attitude to learning.” But I could always draw well. It was only once I began studying illustration at Falmouth School of Art that I was diagnosed as dyslexic. I now view being dyslexic as a talent; less helpful for getting to grips with school textbooks, but invaluable for seeing the world around me. I see things in a more complete way—as an illustrator but also as printmaker, envisaging how several layers of ink came come together to make one visually rich artwork.

I now live in Penryn with my three children: Ned, 15, Billy, 13, and Rosie, 10, in a Georgian home above my shop,7 Broad Street. There, I sell my work alongside pieces by likeminded artists. My flagstoned workshop is at the back in the building’s older core, which dates from sixteenth century. I immediately] loved the feel of its bare brick walls and the pitted stone lintel. I’m drawn towards

earthy pigments and textures, so I’m in my element in here.

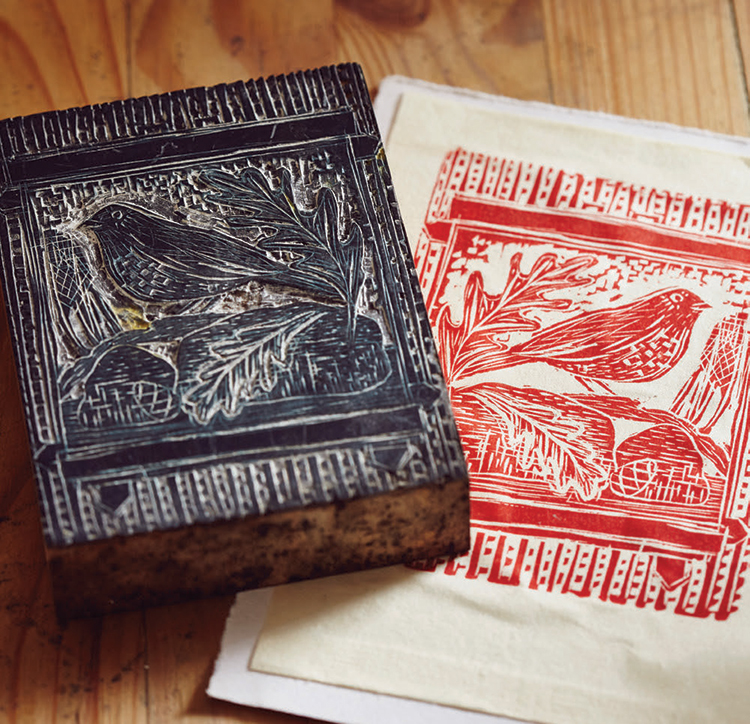

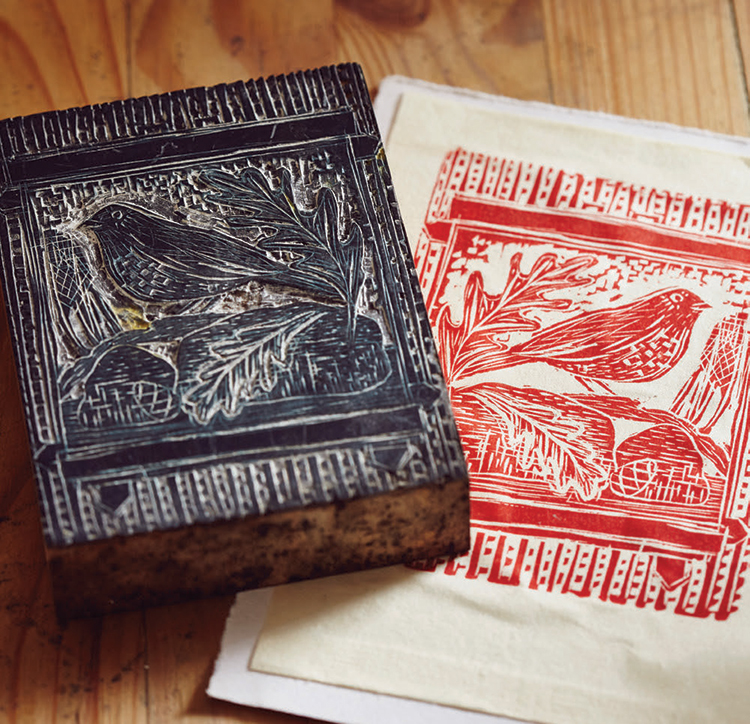

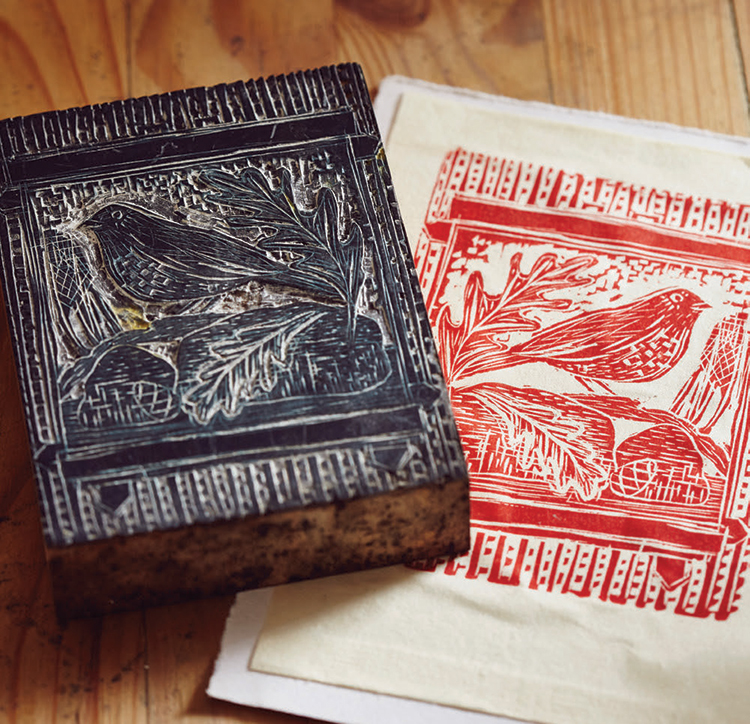

It’s in this space that I spread out my printmaking tools, which include wooden handled blades, lino prints mounted on blocks of wood, stacks of unbleached linen and sheafs of paper. I either print directly onto paper or use my old 19th century iron press, once used to print small books and tracts.

Making a print requires the same calm absorption as those initial sketches that I make while sitting by a riverbank or on a secluded beach. I begin by drawing the larger design onto a block of lino, then slicing away the lino’s soft surface to recreate the image. While I’m guiding the cutter, the tool feels like an extension of my arm. It’s slow, considered work—and it can’t be rushed. There’s no chance to go back and correct a mistake.

Then comes the inking—applied with a roller in just the right amount—before placing the block and a fresh piece of paper into the press. The smell of the ink, even the sound of the heavy metal pressing down, it’s all part of the pleasure. My daughter Rosie sometimes helps; she knows just the right number of turns of the handle so the correct pressure is applied. Press too hard and the ink goes all “blobby.” When I make prints that involve three colours, separate blocks are cut, each inked with a different colour and pressed into the paper in turn. It takes a particular skill to envisage how the images on three different blocks will eventually merge into a single picture on paper.

That moment when I peel the paper away from the final block always gives me a bubble of joy. It still makes me feel like doing a little run around the room.

Cards, limited edition prints and sketch pad covers are all printed here by hand but I enlist the help of local family-run companies for larger items. My tea towels and aprons are screen printed by Lorna Wiles Textiles in Lostwithiel, while Cut By Beam in nearby Mylor laser etches my designs onto enamelware. They might use new technology but it is run from the family’s farm. When I went to collect my latest batch of mugs, the first calf of the season had just been born.

Each time I create a print, I’m also thinking about how it could look on different homewares. I am constantly trying out new ideas—my single feather motif, for example, is now used on napkins, enamel soap dishes and etched into the wooden backs of scrubbing brushes. Even the most ordinary household objects can be made beautiful!

A three-year stint as artist in residence at the Lost Gardens of Heligan helped me understand the kinds of designs that customers love, but it also kept me rooted in my chief inspiration, the Cornish landscape. During that time I kept a words-and-pictures diary, noting what was being planted, changes in the season, or how a song thrush was building its nest. That diary simply put into a more structured form what I have been doing since I was a child, falling in step with the natural rhythm of the countryside.

Because I make a living from my work, every design has to earn its keep.

As I gently trace a path through waist-high reeds along the riverbank, I am looking for a secluded spot where I can sit and sketch. Once I find a nicely hidden nook, I dip down and begin. Lots of my work is about what you see when you find quiet spots like this, it evokes a feeling of sitting patiently and watching nature emerge.

My prints, populated by birds, wildflowers and leaves, all start in this way, with walking out into the Cornish countryside in search of minute details to capture in initial drawings. I begin with dashes of pencil marks that catch the angle of a bird’s cocked head or the curve of its wing in flight. Later, back at my workshop, I will add in more details in ink and work those images into stylised scenes. These designs are later painstakingly carved into lino blocks and then hand-printed onto paper or linen.

The idea for the larger design tends to come together as I head home after a morning’s sketching. As I retrace my steps, it takes shape in my mind’s eye. And even that steady act of walking is all part of the creative process; if I have to get in the car afterwards and drive, it’s never quite the same—I lose my thread.

To draw, I need to be immersed in nature and to follow its slow, steady rhythms.

This love of wandering through the Cornish countryside is something I have done since childhood. My best memories are of exploring the narrow lanes and hedgerows around St Erth with my Grandpa. It wasn’t about getting somewhere; it was more of an idle dawdle. We’d carry thumb sticks to swish away stinging nettles and I’d pick little posies of wildflowers. It was all very gentle, very kind. He slowed everything down to my child’s pace.

My grandfather and I called our outings ‘hedgerow grazing’ and that habit of literally combing the foliage to seek out small creatures, buds and flowers stood me in good stead for my career as an artist. I think taking time to look really closely helped develop my eye for detail.

I grew up in Crowan, a village in Cornwall’s former mining heartland, and then the wilder coastal setting of St Just. My school reports tended to dismiss me as “lazy” or said I had “a poor attitude to learning.” But I could always draw well. It was only once I began studying illustration at Falmouth School of Art that I was diagnosed as dyslexic. I now view being dyslexic as a talent; less helpful for getting to grips with school textbooks, but invaluable for seeing the world around me. I see things in a more complete way—as an illustrator but also as printmaker, envisaging how several layers of ink came come together to make one visually rich artwork.

I now live in Penryn with my three children: Ned, 15, Billy, 13, and Rosie, 10, in a Georgian home above my shop,7 Broad Street. There, I sell my work alongside pieces by likeminded artists. My flagstoned workshop is at the back in the building’s older core, which dates from sixteenth century. I immediately] loved the feel of its bare brick walls and the pitted stone lintel. I’m drawn towards

earthy pigments and textures, so I’m in my element in here.

It’s in this space that I spread out my printmaking tools, which include wooden handled blades, lino prints mounted on blocks of wood, stacks of unbleached linen and sheafs of paper. I either print directly onto paper or use my old 19th century iron press, once used to print small books and tracts.

Making a print requires the same calm absorption as those initial sketches that I make while sitting by a riverbank or on a secluded beach. I begin by drawing the larger design onto a block of lino, then slicing away the lino’s soft surface to recreate the image. While I’m guiding the cutter, the tool feels like an extension of my arm. It’s slow, considered work—and it can’t be rushed. There’s no chance to go back and correct a mistake.

Then comes the inking—applied with a roller in just the right amount—before placing the block and a fresh piece of paper into the press. The smell of the ink, even the sound of the heavy metal pressing down, it’s all part of the pleasure. My daughter Rosie sometimes helps; she knows just the right number of turns of the handle so the correct pressure is applied. Press too hard and the ink goes all “blobby.” When I make prints that involve three colours, separate blocks are cut, each inked with a different colour and pressed into the paper in turn. It takes a particular skill to envisage how the images on three different blocks will eventually merge into a single picture on paper.

That moment when I peel the paper away from the final block always gives me a bubble of joy. It still makes me feel like doing a little run around the room.

Cards, limited edition prints and sketch pad covers are all printed here by hand but I enlist the help of local family-run companies for larger items. My tea towels and aprons are screen printed by Lorna Wiles Textiles in Lostwithiel, while Cut By Beam in nearby Mylor laser etches my designs onto enamelware. They might use new technology but it is run from the family’s farm. When I went to collect my latest batch of mugs, the first calf of the season had just been born.

Each time I create a print, I’m also thinking about how it could look on different homewares. I am constantly trying out new ideas—my single feather motif, for example, is now used on napkins, enamel soap dishes and etched into the wooden backs of scrubbing brushes. Even the most ordinary household objects can be made beautiful!

A three-year stint as artist in residence at the Lost Gardens of Heligan helped me understand the kinds of designs that customers love, but it also kept me rooted in my chief inspiration, the Cornish landscape. During that time I kept a words-and-pictures diary, noting what was being planted, changes in the season, or how a song thrush was building its nest. That diary simply put into a more structured form what I have been doing since I was a child, falling in step with the natural rhythm of the countryside.

Because I make a living from my work, every design has to earn its keep.