I have been a maker and artist for as long as I remember. At times, this facet of my existence has been pushed back by the pressures of a corporate career in law and parenting young children. And later, by shepherding and supporting my wonderful teenagers into young adulthood. But our lives develop and change, and this has provided me with the opportunity to focus my attention on making art and other unique things.

With today’s renewed emphasis on simplicity, durability and authenticity, I feel my eco printing practice and product are quite on-point. I got to this by taking the long route. No art school or decades on a design team feature as a part of my bio, but I did have a robust childhood in South Africa’s rural KwaZulu-Natal (1800km and an entire ecosystem away from where I now live), which taught me, among several other country-girl skills, to sew and to identify the plants and trees that grew abundantly around me. In contrast, this was followed by a high-powered 13-year stint in corporate law.

While I was super-fluent about fabric and flora from the get-go, where I am now as a surface designer is as much a science as it is about art; as much about precision, chemistry and biology as it is about the more soulful stuff of documenting time and place in my surroundings in a way that others, I hope, can enjoy.

My objective with my brand, Inyoni—the isiZulu word for bird, which was my dad’s nickname for me—was to produce wearable and usable art. The art part is the design element, the visualization of a piece based on prior knowledge of how the foliage I find will transfer onto fabric. So it’s really about a look and feel I’d like to achieve, plus it is about registering or transferring memory onto a textile, and in that way it is completely different from any mechanical process.

The science part turned out to be considerably more dicey, alchemic and experimental. There is very little written on the science, as opposed to the practice, of eco printing. Each piece of fabric I make is botanically printed directly from the pigments intrinsic to the foliage. I don’t use inks, dye or chemicals. Nature does the work. There were a lot of eureka moments. You don’t know until you know.

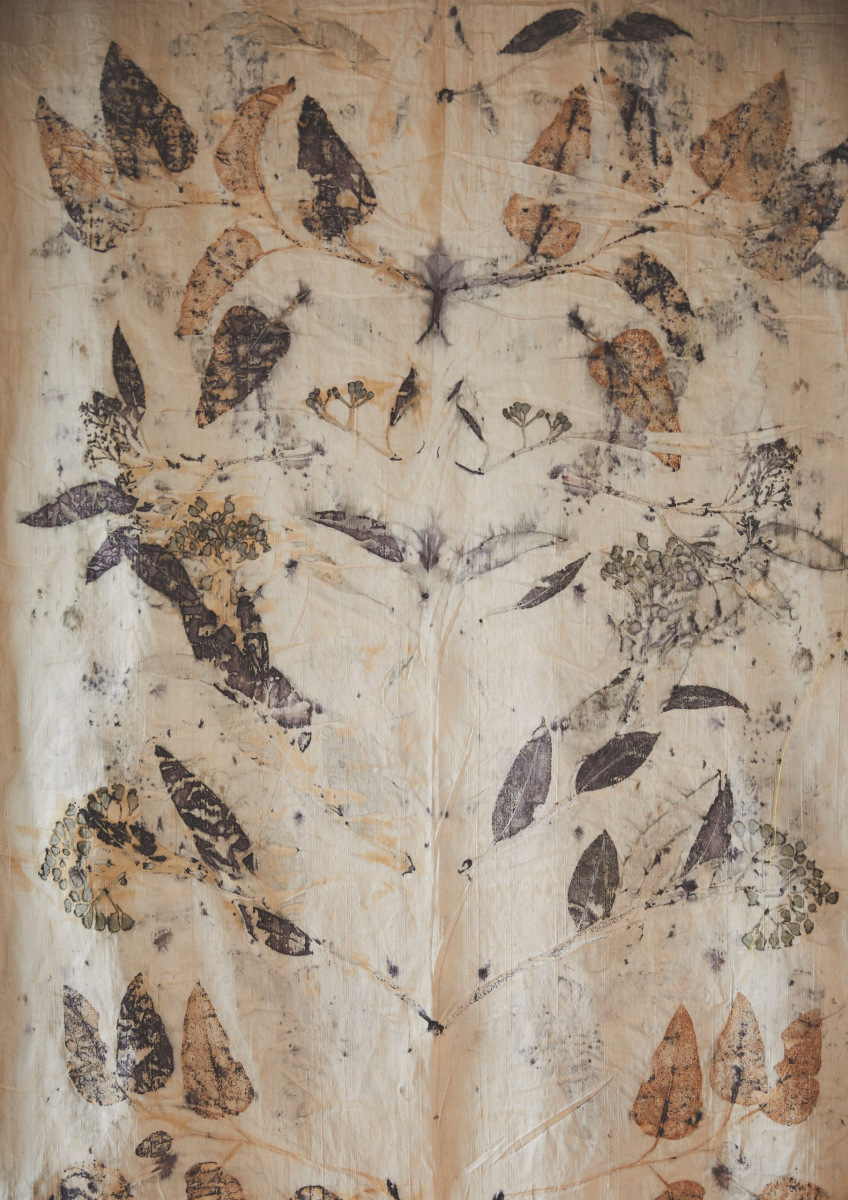

With a thicket of winter-flowering Lobostemon glaucophyllus or ‘agtdaegeneesbos’ as it is locally known, which I favour for its distinct sketchy print. It is like a soft charcoal drawing, clearly showing the leaf vein and shape and the funnel-shaped bloom. I print off it for the varied foliage structure and as my own recording on the cloth of its short flowering season.

Having unlocked this mysterious process through initiative and time-intensive experimentation, I’m not about to dish on how you can DIY. After all, the product is not the method but what is expressed on the material. What I will tell you, however, is that I don’t get results by being an elite forager. Although the Cape Floral Kingdom—one of six unique floral kingdoms in the world and widely lauded for its extraordinary diversity of endemic species—is on my doorstep, my foraging is far from restricted to plant royalty. I pick indigenous fynbos, legally, in the suburban areas around my Kommetjie studio, but also use kitchen scraps—like onion skin; alien plants such as peppermint willow (Agonis flexuosa), a native to Australia that features on the street verges of Kommetjie; and the bankrupt bush (Seriphium plumosum), which though indigenous tends to encroach aggressively wherever it’s planted. In fact, my preferred picking grounds are gutters, plant dumps and the suburban paths and byways where plants have spilled over onto the public thoroughfare.

Eco-printing

Submerging cloth into a solution of rusty water that is used as a mordant to allow the pigment in the foliage to make a colourfast imprint on the cloth. The cloth and sometimes the foliage are dipped in this solution.

I begin the process of arranging the foraged foliage slips onto fabric, and then rolling them into a tight bundle.

When I forage, I already have in mind a look and feel I’d like to achieve with a piece, so I scavenge for what I need. Perhaps the beautiful blombos (Metalasia muricata) in bloom or the thin straplike leaves of the invasive Port Jackson (Acacia siligna) that prints medium grey and slightly haphazard in structure. I particularly love the scribbled, needle-fine casuarina. To create depth in my pieces, I compose and juxtapose relative-strength pigments and foliage shapes, plus the negative space around the foliage and the general markings left on the fabric to create surface noise or detail. All this is on my mind when I forage for and execute a print.

Fynbos and other locally foraged plants chosen for their precise printing qualities are rolled up in fabric and trussed with natural twine, ready for dyeing.

I have gone from producing small-batch fabric lengths that retail through several high-end Cape Town craft galleries to producing a homeware range of cushions, bed throws, tea towels and table napkins, available on my website. I have also ventured into fashion design, through a collab with fashion designer Nadya Von Stein, whose bespoke range of hemp resort wear well fits my values. For this, and my own growing range of textile prints for Inyoni, I’m determined to retain my bespoke approach but reach a wider fashion-focused audience that appreciates and champions small-batch big-time makers of wearable art.

Woodblock Prints

Though my art techniques are diverse, what my work has in common is a message from me to the viewer. It is intimate and personal, and it is my lived experience and thought. Fortunately, as we are all humans, my messages resonate with other people who have similar notions and memories. They may not have been to the place depicted in my landscape woodblock print, but they have felt like that in their own place. They may not have had to worry about their child completing their final year of high school with covid hanging in the wings, but they will have felt the angst of an uncertain future in unpredictable times.

With this as an underlying theme, my art practice has evolved. I spend the majority of my time working on fine art printmaking, making limited edition woodblock prints. They often have multiple layers of colour, printed off a number of carved wooden blocks or using the reduction technique.

Mixing and testing colours. I use oil based Litho ink in the process colours of cyan, magenta and yellow, as well as opaque white and black. From that, I mix the colours that I use in my woodblock printmaking. I have always mixed my own colours, as opposed to purchasing a large range of colours in tubes, as it gives me greater control over the subtle graduation of natural colour and tone.

Inking up and printing the second layer of the print. I have carved away tiny marks that will appear as white or yellow, on the final print. I am using a handmade brayer by Lucas Nkgweng. He is based in Johannesburg, South Africa, and makes professional printmaking brayers and rollers which head all over the world.

I have carved away the sky and highlights on the rocks and grass, ready to print up the next layer. You can clearly see the Jelutong woodblock that I am carving and printing. This is my preferred wood for printmaking; a light-weight wood from South East Asia, which is comfortable to cut into and has a lovely grain.

Layer 5 of the woodblock is carved, inked up and printed. Quite dramatic changes can now be seen in the print, with the forms in the foreground taking shape. This is especially clear when comparing the print at the stage of layer 4 and 5.

The last year has found me in a state of flux. A time of empty nests and shifting roles and unclear paths ahead. In this time, certain spaces and ideas have grounded me, providing permanence and assurance. It is to these places that I turn, to settle myself and calm my darting thoughts. Living in the beautiful wild area that I do, on an exposed coastline, the places that I go are inevitably in nature. With giant rocks and open vistas and shifting skies and no other humans around. This year, I have resumed a habit of sitting quietly in these places and making water colour sketches of what I see. An attempt to capture the essence of the surroundings and what I feel sitting there. These are the spaces I present in my woodblocks landscape prints—layers of subtle colour, slowly built up to achieve the quiet and permanence of the place.

I make my woodblock prints in small editions of between 5 and 15 prints, each one made by my hand in my studio. Every print is an original piece of art. It is a physical and thoughtful process, working in reverse and from light to dark. I really need to concentrate to achieve my envisioned result, so I work in blocks of time, with quite a strict schedule. Starting my day with a walk with my husband Andy and staffie dog Axl. Then breakfast and admin chores, invoices and payments and social media interaction. And then I settle into my studio with a coffee and a sleepy dog, and work until lunch time, have a break, and again until around 5. Monday to Friday, and unless I’m behind on my work or something is very pressing, I take the weekends off, out of the studio, to explore and rest and read and stitch.

The Jelutong block is carved away to print Layer 6 on the print. At each point I refer back to my loose planning notes of what layers will apply to each area of the print. My whetstone is always in my workspace, to keep my tools sharp.

Slow Stitching

My stitch work is my therapy. I have worked with cloth and thread since I was a little girl, making clothes and special pieces by hand and machine, always to my own pattern and style. A few years ago, I started reducing my thoughts onto cloth, messages and memories stitched in place and there forever. It started with free hand embroidered words and symbols on a single crochet base, to make a small message cushion for my teenager. It morphed from there to my current practice of layering scraps of eco printed cloth on a base of linen, incorporating special items and ideas, to tell a story or record what is going on in my head. A stitched memory of lockdown or a message to my younger self or my struggles with balance and time.

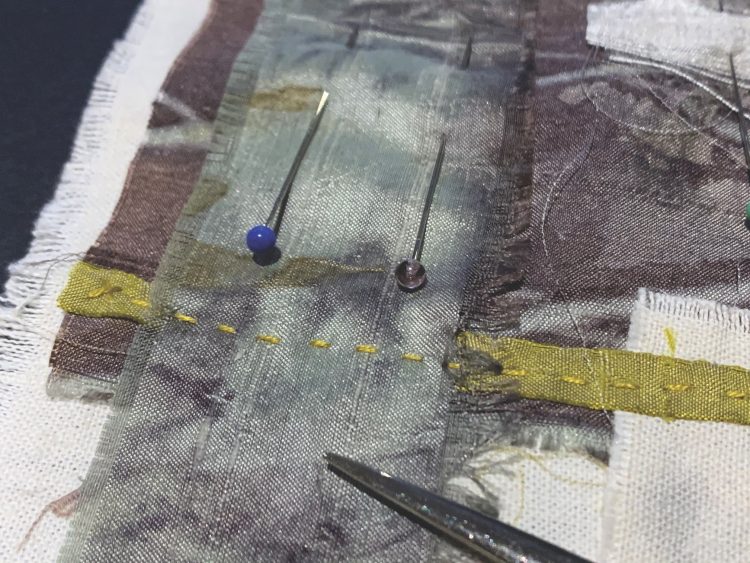

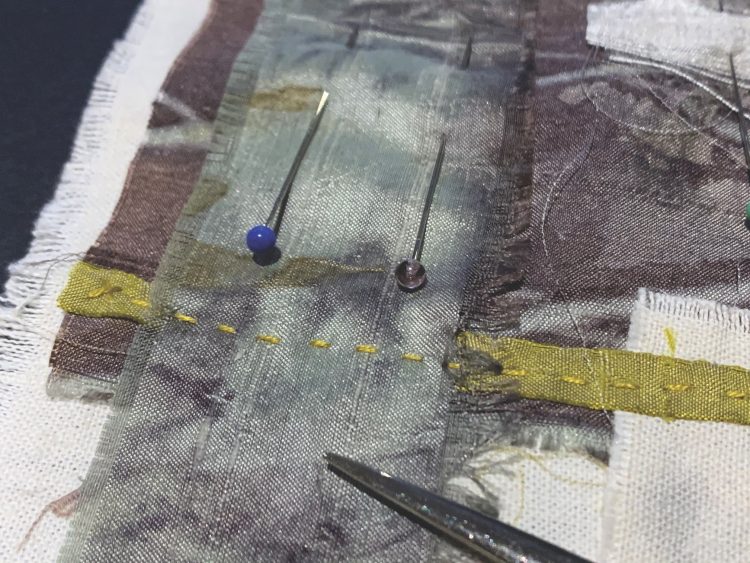

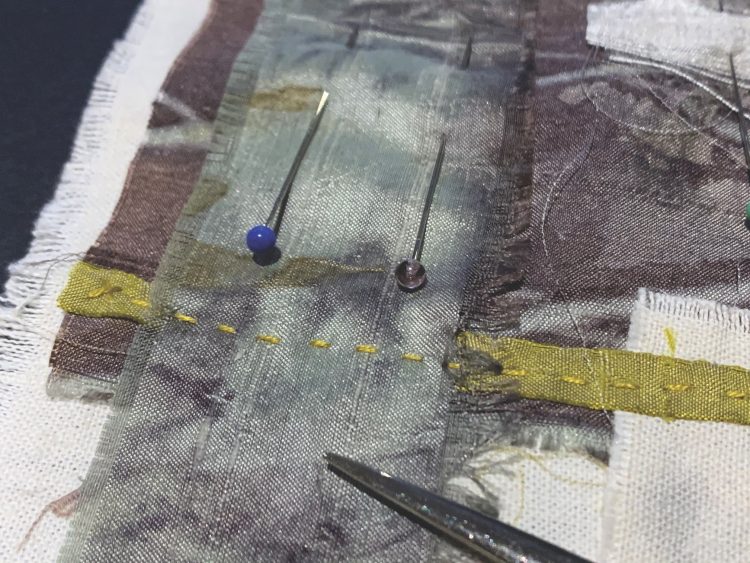

I start by laying the elements out in the way that makes sense to me. I secure the scraps with straight pins, and then start with a running stitch through the piece to fix all the elements onto my base cloth, so that I can work without the pins. The would-be-discarded scraps or patches overlap in a style inspired by Japanese Boro mending and reinforcing, with Sashiko stitches running in lines, this way and that.

Once the scraps are stitched in place and lay flat, I use an embroidery ring to support the cloth while I stitch some of the elements.

The size 10 label has been stitched into the piece. When I removed the label from the deconstructed bridesmaid skirt, it was marked with a pencil “L” but when I turned the tiny label over, I found a printed “10”. The idea of the wearer being regarded as a large, struck me as ironic as she was in fact a “Perfect 10”. She was both. It made me think of society’s ideas of what is good or desirable, and how that is all just nonsense.

The button-hole from the skirt is stitched in place with a backing of hemp linen, ecoprinted with eucalyptus. Small things that would otherwise be discarded but still have value, playing a role of reinforcement on this tiny message cloth. Details are slowly added, scraps that are first joined and then stitched onto the cloth. A repeat pattern of circles emerges.

If we are perfectly ourselves, then we are perfect as we are.

I generally stitch in the evening. A ritual of quietening and slowing down from a day spent in my busy studio, to a state of rest. I take my time with each piece, slowly putting together concepts and stitches and scraps. Adding a word or even a word search. An unbeatable game of noughts and crosses. A window into what is behind. One piece could take a few weeks or a few months. It is a practice that cannot be rushed otherwise the message is lost. As personal as these pieces are, I love it when they leave me, beautifully framed or mounted to be framed in another city or country. Then I know my message has travelled and will sit in a different place and impact people who I have never met.

The finished artwork: “A perfect 10” 2021 Message cloth with slow stitch and free hand embroidery on ecoprinted and other scraps of fabric

I have been a maker and artist for as long as I remember. At times, this facet of my existence has been pushed back by the pressures of a corporate career in law and parenting young children. And later, by shepherding and supporting my wonderful teenagers into young adulthood. But our lives develop and change, and this has provided me with the opportunity to focus my attention on making art and other unique things.

With today’s renewed emphasis on simplicity, durability and authenticity, I feel my eco printing practice and product are quite on-point. I got to this by taking the long route. No art school or decades on a design team feature as a part of my bio, but I did have a robust childhood in South Africa’s rural KwaZulu-Natal (1800km and an entire ecosystem away from where I now live), which taught me, among several other country-girl skills, to sew and to identify the plants and trees that grew abundantly around me. In contrast, this was followed by a high-powered 13-year stint in corporate law.

While I was super-fluent about fabric and flora from the get-go, where I am now as a surface designer is as much a science as it is about art; as much about precision, chemistry and biology as it is about the more soulful stuff of documenting time and place in my surroundings in a way that others, I hope, can enjoy.

My objective with my brand, Inyoni—the isiZulu word for bird, which was my dad’s nickname for me—was to produce wearable and usable art. The art part is the design element, the visualization of a piece based on prior knowledge of how the foliage I find will transfer onto fabric. So it’s really about a look and feel I’d like to achieve, plus it is about registering or transferring memory onto a textile, and in that way it is completely different from any mechanical process.

The science part turned out to be considerably more dicey, alchemic and experimental. There is very little written on the science, as opposed to the practice, of eco printing. Each piece of fabric I make is botanically printed directly from the pigments intrinsic to the foliage. I don’t use inks, dye or chemicals. Nature does the work. There were a lot of eureka moments. You don’t know until you know.

With a thicket of winter-flowering Lobostemon glaucophyllus or ‘agtdaegeneesbos’ as it is locally known, which I favour for its distinct sketchy print. It is like a soft charcoal drawing, clearly showing the leaf vein and shape and the funnel-shaped bloom. I print off it for the varied foliage structure and as my own recording on the cloth of its short flowering season.

Having unlocked this mysterious process through initiative and time-intensive experimentation, I’m not about to dish on how you can DIY. After all, the product is not the method but what is expressed on the material. What I will tell you, however, is that I don’t get results by being an elite forager. Although the Cape Floral Kingdom—one of six unique floral kingdoms in the world and widely lauded for its extraordinary diversity of endemic species—is on my doorstep, my foraging is far from restricted to plant royalty. I pick indigenous fynbos, legally, in the suburban areas around my Kommetjie studio, but also use kitchen scraps—like onion skin; alien plants such as peppermint willow (Agonis flexuosa), a native to Australia that features on the street verges of Kommetjie; and the bankrupt bush (Seriphium plumosum), which though indigenous tends to encroach aggressively wherever it’s planted. In fact, my preferred picking grounds are gutters, plant dumps and the suburban paths and byways where plants have spilled over onto the public thoroughfare.

Eco-printing

Submerging cloth into a solution of rusty water that is used as a mordant to allow the pigment in the foliage to make a colourfast imprint on the cloth. The cloth and sometimes the foliage are dipped in this solution.

I begin the process of arranging the foraged foliage slips onto fabric, and then rolling them into a tight bundle.

When I forage, I already have in mind a look and feel I’d like to achieve with a piece, so I scavenge for what I need. Perhaps the beautiful blombos (Metalasia muricata) in bloom or the thin straplike leaves of the invasive Port Jackson (Acacia siligna) that prints medium grey and slightly haphazard in structure. I particularly love the scribbled, needle-fine casuarina. To create depth in my pieces, I compose and juxtapose relative-strength pigments and foliage shapes, plus the negative space around the foliage and the general markings left on the fabric to create surface noise or detail. All this is on my mind when I forage for and execute a print.

Fynbos and other locally foraged plants chosen for their precise printing qualities are rolled up in fabric and trussed with natural twine, ready for dyeing.

I have gone from producing small-batch fabric lengths that retail through several high-end Cape Town craft galleries to producing a homeware range of cushions, bed throws, tea towels and table napkins, available on my website. I have also ventured into fashion design, through a collab with fashion designer Nadya Von Stein, whose bespoke range of hemp resort wear well fits my values. For this, and my own growing range of textile prints for Inyoni, I’m determined to retain my bespoke approach but reach a wider fashion-focused audience that appreciates and champions small-batch big-time makers of wearable art.

Woodblock Prints

Though my art techniques are diverse, what my work has in common is a message from me to the viewer. It is intimate and personal, and it is my lived experience and thought. Fortunately, as we are all humans, my messages resonate with other people who have similar notions and memories. They may not have been to the place depicted in my landscape woodblock print, but they have felt like that in their own place. They may not have had to worry about their child completing their final year of high school with covid hanging in the wings, but they will have felt the angst of an uncertain future in unpredictable times.

With this as an underlying theme, my art practice has evolved. I spend the majority of my time working on fine art printmaking, making limited edition woodblock prints. They often have multiple layers of colour, printed off a number of carved wooden blocks or using the reduction technique.

Mixing and testing colours. I use oil based Litho ink in the process colours of cyan, magenta and yellow, as well as opaque white and black. From that, I mix the colours that I use in my woodblock printmaking. I have always mixed my own colours, as opposed to purchasing a large range of colours in tubes, as it gives me greater control over the subtle graduation of natural colour and tone.

Inking up and printing the second layer of the print. I have carved away tiny marks that will appear as white or yellow, on the final print. I am using a handmade brayer by Lucas Nkgweng. He is based in Johannesburg, South Africa, and makes professional printmaking brayers and rollers which head all over the world.

I have carved away the sky and highlights on the rocks and grass, ready to print up the next layer. You can clearly see the Jelutong woodblock that I am carving and printing. This is my preferred wood for printmaking; a light-weight wood from South East Asia, which is comfortable to cut into and has a lovely grain.

Layer 5 of the woodblock is carved, inked up and printed. Quite dramatic changes can now be seen in the print, with the forms in the foreground taking shape. This is especially clear when comparing the print at the stage of layer 4 and 5.

The last year has found me in a state of flux. A time of empty nests and shifting roles and unclear paths ahead. In this time, certain spaces and ideas have grounded me, providing permanence and assurance. It is to these places that I turn, to settle myself and calm my darting thoughts. Living in the beautiful wild area that I do, on an exposed coastline, the places that I go are inevitably in nature. With giant rocks and open vistas and shifting skies and no other humans around. This year, I have resumed a habit of sitting quietly in these places and making water colour sketches of what I see. An attempt to capture the essence of the surroundings and what I feel sitting there. These are the spaces I present in my woodblocks landscape prints—layers of subtle colour, slowly built up to achieve the quiet and permanence of the place.

I make my woodblock prints in small editions of between 5 and 15 prints, each one made by my hand in my studio. Every print is an original piece of art. It is a physical and thoughtful process, working in reverse and from light to dark. I really need to concentrate to achieve my envisioned result, so I work in blocks of time, with quite a strict schedule. Starting my day with a walk with my husband Andy and staffie dog Axl. Then breakfast and admin chores, invoices and payments and social media interaction. And then I settle into my studio with a coffee and a sleepy dog, and work until lunch time, have a break, and again until around 5. Monday to Friday, and unless I’m behind on my work or something is very pressing, I take the weekends off, out of the studio, to explore and rest and read and stitch.

The Jelutong block is carved away to print Layer 6 on the print. At each point I refer back to my loose planning notes of what layers will apply to each area of the print. My whetstone is always in my workspace, to keep my tools sharp.

Slow Stitching

My stitch work is my therapy. I have worked with cloth and thread since I was a little girl, making clothes and special pieces by hand and machine, always to my own pattern and style. A few years ago, I started reducing my thoughts onto cloth, messages and memories stitched in place and there forever. It started with free hand embroidered words and symbols on a single crochet base, to make a small message cushion for my teenager. It morphed from there to my current practice of layering scraps of eco printed cloth on a base of linen, incorporating special items and ideas, to tell a story or record what is going on in my head. A stitched memory of lockdown or a message to my younger self or my struggles with balance and time.

I start by laying the elements out in the way that makes sense to me. I secure the scraps with straight pins, and then start with a running stitch through the piece to fix all the elements onto my base cloth, so that I can work without the pins. The would-be-discarded scraps or patches overlap in a style inspired by Japanese Boro mending and reinforcing, with Sashiko stitches running in lines, this way and that.

Once the scraps are stitched in place and lay flat, I use an embroidery ring to support the cloth while I stitch some of the elements.

The size 10 label has been stitched into the piece. When I removed the label from the deconstructed bridesmaid skirt, it was marked with a pencil “L” but when I turned the tiny label over, I found a printed “10”. The idea of the wearer being regarded as a large, struck me as ironic as she was in fact a “Perfect 10”. She was both. It made me think of society’s ideas of what is good or desirable, and how that is all just nonsense.

The button-hole from the skirt is stitched in place with a backing of hemp linen, ecoprinted with eucalyptus. Small things that would otherwise be discarded but still have value, playing a role of reinforcement on this tiny message cloth. Details are slowly added, scraps that are first joined and then stitched onto the cloth. A repeat pattern of circles emerges.

If we are perfectly ourselves, then we are perfect as we are.

I generally stitch in the evening. A ritual of quietening and slowing down from a day spent in my busy studio, to a state of rest. I take my time with each piece, slowly putting together concepts and stitches and scraps. Adding a word or even a word search. An unbeatable game of noughts and crosses. A window into what is behind. One piece could take a few weeks or a few months. It is a practice that cannot be rushed otherwise the message is lost. As personal as these pieces are, I love it when they leave me, beautifully framed or mounted to be framed in another city or country. Then I know my message has travelled and will sit in a different place and impact people who I have never met.

The finished artwork: “A perfect 10” 2021 Message cloth with slow stitch and free hand embroidery on ecoprinted and other scraps of fabric