I live in Camberwell, South London, UK. A lot of people think that because of the ethos behind Good Shepherd, I live in the countryside! However, I love both city and country life and find they equally influence my work. Because what I create can clearly be traced back to the original source in a rural setting, people assume that I am working there too. However part of what I’m trying to highlight is that there is a wealth of raw material on our doorsteps in the UK and that there is no reason why it can’t be placed in a design-led, attractive context.

I didn’t grow up in the city or the countryside but the suburbs in Hampshire. However, my parents were keen outdoors people, and from the get-go there was hardly a weekend where we weren’t in a National park or on the coast. It was here that my love of nature began, and my desire to connect with the landscape; both respecting it and utilising what it provided. My parents were teachers, and in the school holidays I remember going in to school with my mum (an English teacher) to create displays themed around the books she was teaching that term — one time we covered an entire wall with seashells we’d collected on the beach. I forget what the book was, but I remember the display! My mum had this fantastic can-do attitude; when I asked how something was made, she’d simply say let’s give it a go. Often this would involve referring a certain project to grandma, she wouldn’t necessarily be able to tell you how to make something (“I just made it up”) but she would be able to show you. My grandma was the woman that taught me to knit and it always amused her to see where I had taken that skill. I owe the desire and ability to create to the matriarchs in my life.

Creating has always been in my life in some capacity. I don’t remember when it started, yet I have always had a restlessness to know how something is made, constructed. However, when I was younger, what I was creating never really felt like enough, what I was making needed to be pushed further. Doing my MA at the Royal College of Art (Textiles, Knit) really helped me hone in to my obsessive desire to create and fine-tune what I was trying to achieve.

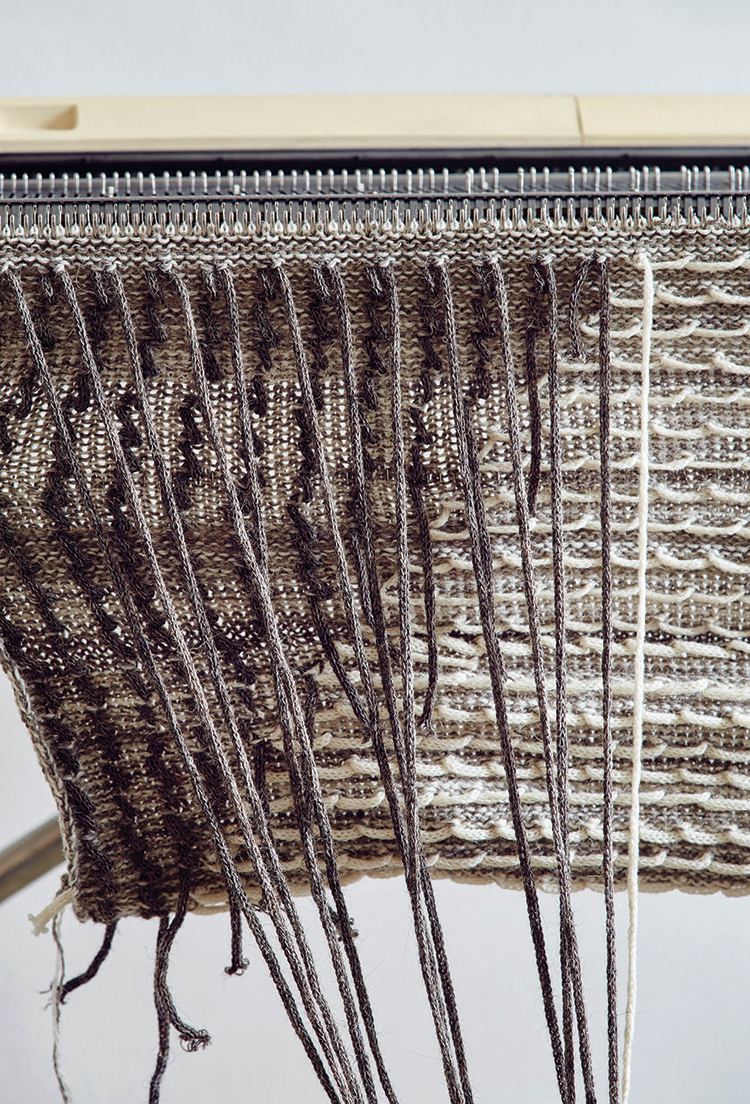

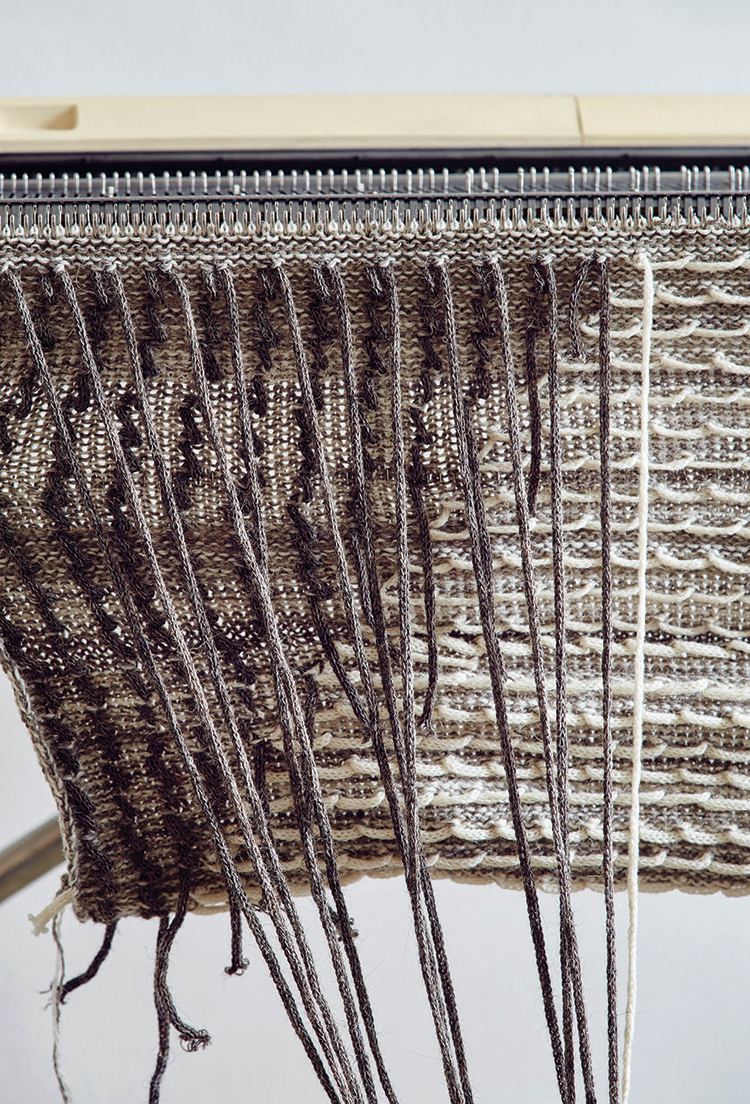

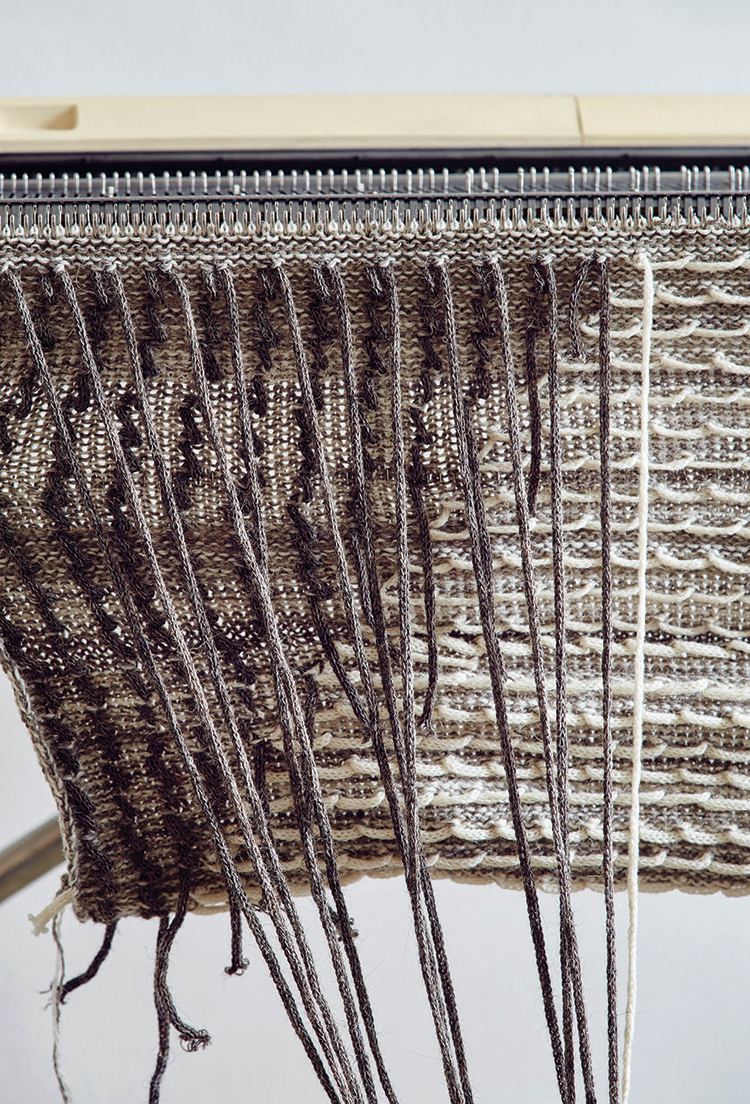

My creative process often starts with a walk! It doesn’t matter where I am, in the city or the country, when I’m walking something catches my eye. It can be a natural form, or how a building is constructed, the pattern achieved either by man or nature. I then focus on one part and experiment with different ways of creating that construction within my textiles. I keep the end product created very simple, allowing the design or texture of the textile to be the focus, with an emphasis on hand processes — all my cushions are hand-stitched. The end look is simple, clean and graphic, but the processes behind it often involve multiple yarns, spinners and breeds of sheep.

I would say that my appreciation for how things are designed and created has grown and therefore I am more careful about what I choose to have around me.

I think I’m quite strict with myself and my creative style is distinct. For me it feeds my practice to have clear boundaries, such as only working with British wool and only working with naturally coloured wools. Yet within these bounds I find infinite combinations, and having these presets allows me to focus on creating the possibilities I imagine.

I love looking at vintage knitwear. Traditional Aran jumpers, Guernseys, hand-knit items — I’m building up a jumper reference library. I love to see how past generations have made things and look at the traditional patterns and stitches — each maker had their own handwriting.

My biggest challenge is that currently everything is made by me personally and at some point you reach capacity. I’d like start working with a small network where my designs could be achieved together by artists within the UK. Creating is rooted in both your past and present environments. My aim is to create desirable objects that celebrate locality and champion sustainability without compromising the design.

My company, The Good Shepherd, is named after the ferry that connects the island of Fair Isle (a knitter’s pilgrimage!) to mainland Shetland. This ferry is responsible for bringing over supplies ranging from cars to sheep to groceries. There are small planes that connect the islands, but when the weather becomes more lively, The Good Shepherd carries on serving Fair Isle faithfully. The name also reflects my wish to make the best of the fleece that comes from so many flocks — to be a good shepherd.

P.S I Love This

My favourite item in my studio is the industrial work light I have that pivots over my desk and work station. This light used to hang in my grandpa’s workshop where he would build anything from a wooden surfboard to a toy sailing boat. It hung there for probably 50 years and when he passed away and when the house was sold this was one of the few objects that I was able to save. I like that the light continues to oversee creative endeavours.

“We must come down to earth from the clouds where we live in vagueness, and experience the most real thing there is: material.”

— Anni Albers

I choose to use only British wool — that means grown and spun in the UK. For me, it’s about a connection to my environment: What is local? What resources can you utilise and make the best of? I hate the idea of readily available renewable fibre, such as wool, going to waste. Living in the UK means making that choice to use what is available here. This has undoubtedly shaped the textiles I make — colour and fibre mostly. The UK has a fantastic history with wool and indeed it was a dominant part of trade and industry; as such there is a huge amount of information, inspiration, history and tradition available to draw upon to make new work. The UK does seem to be a place where rare-breed sheep and a more specialised fibre industry is thriving. I do feel that this commitment to utilising local materials and drawing upon history and tradition is very much transferable (and already happening) to other countries, e.g. Iceland. I see this as a positive and exciting trend in design and craft.

It’s very much an ethical choice: utilising what is around you. The calibre of the fibres from breeds of sheep in the UK is exceptional and I suppose the challenge is finding the right supply chain. The more that people know about the versatility of British wool, the higher the demand will be and the supply should follow the incline. There are fantastic mills in the UK spinning British wool, but there is definitely room for growth. On an aesthetic side there is also a wealth of possibilities for designs in only using British wool: whilst initially it can be restrictive and challenging opting to use one material source, ultimately, as a designer, it makes you more resourceful and challenges your practice and I feel stronger for it.

Once you restrict your palette, when you look a little closer, you realise there are many subtleties within it and a lot of scope for design.

I live in Camberwell, South London, UK. A lot of people think that because of the ethos behind Good Shepherd, I live in the countryside! However, I love both city and country life and find they equally influence my work. Because what I create can clearly be traced back to the original source in a rural setting, people assume that I am working there too. However part of what I’m trying to highlight is that there is a wealth of raw material on our doorsteps in the UK and that there is no reason why it can’t be placed in a design-led, attractive context.

I didn’t grow up in the city or the countryside but the suburbs in Hampshire. However, my parents were keen outdoors people, and from the get-go there was hardly a weekend where we weren’t in a National park or on the coast. It was here that my love of nature began, and my desire to connect with the landscape; both respecting it and utilising what it provided. My parents were teachers, and in the school holidays I remember going in to school with my mum (an English teacher) to create displays themed around the books she was teaching that term — one time we covered an entire wall with seashells we’d collected on the beach. I forget what the book was, but I remember the display! My mum had this fantastic can-do attitude; when I asked how something was made, she’d simply say let’s give it a go. Often this would involve referring a certain project to grandma, she wouldn’t necessarily be able to tell you how to make something (“I just made it up”) but she would be able to show you. My grandma was the woman that taught me to knit and it always amused her to see where I had taken that skill. I owe the desire and ability to create to the matriarchs in my life.

Creating has always been in my life in some capacity. I don’t remember when it started, yet I have always had a restlessness to know how something is made, constructed. However, when I was younger, what I was creating never really felt like enough, what I was making needed to be pushed further. Doing my MA at the Royal College of Art (Textiles, Knit) really helped me hone in to my obsessive desire to create and fine-tune what I was trying to achieve.

My creative process often starts with a walk! It doesn’t matter where I am, in the city or the country, when I’m walking something catches my eye. It can be a natural form, or how a building is constructed, the pattern achieved either by man or nature. I then focus on one part and experiment with different ways of creating that construction within my textiles. I keep the end product created very simple, allowing the design or texture of the textile to be the focus, with an emphasis on hand processes — all my cushions are hand-stitched. The end look is simple, clean and graphic, but the processes behind it often involve multiple yarns, spinners and breeds of sheep.

I would say that my appreciation for how things are designed and created has grown and therefore I am more careful about what I choose to have around me.

I think I’m quite strict with myself and my creative style is distinct. For me it feeds my practice to have clear boundaries, such as only working with British wool and only working with naturally coloured wools. Yet within these bounds I find infinite combinations, and having these presets allows me to focus on creating the possibilities I imagine.

I love looking at vintage knitwear. Traditional Aran jumpers, Guernseys, hand-knit items — I’m building up a jumper reference library. I love to see how past generations have made things and look at the traditional patterns and stitches — each maker had their own handwriting.

My biggest challenge is that currently everything is made by me personally and at some point you reach capacity. I’d like start working with a small network where my designs could be achieved together by artists within the UK. Creating is rooted in both your past and present environments. My aim is to create desirable objects that celebrate locality and champion sustainability without compromising the design.

My company, The Good Shepherd, is named after the ferry that connects the island of Fair Isle (a knitter’s pilgrimage!) to mainland Shetland. This ferry is responsible for bringing over supplies ranging from cars to sheep to groceries. There are small planes that connect the islands, but when the weather becomes more lively, The Good Shepherd carries on serving Fair Isle faithfully. The name also reflects my wish to make the best of the fleece that comes from so many flocks — to be a good shepherd.

P.S I Love This

My favourite item in my studio is the industrial work light I have that pivots over my desk and work station. This light used to hang in my grandpa’s workshop where he would build anything from a wooden surfboard to a toy sailing boat. It hung there for probably 50 years and when he passed away and when the house was sold this was one of the few objects that I was able to save. I like that the light continues to oversee creative endeavours.

“We must come down to earth from the clouds where we live in vagueness, and experience the most real thing there is: material.”

— Anni Albers

I choose to use only British wool — that means grown and spun in the UK. For me, it’s about a connection to my environment: What is local? What resources can you utilise and make the best of? I hate the idea of readily available renewable fibre, such as wool, going to waste. Living in the UK means making that choice to use what is available here. This has undoubtedly shaped the textiles I make — colour and fibre mostly. The UK has a fantastic history with wool and indeed it was a dominant part of trade and industry; as such there is a huge amount of information, inspiration, history and tradition available to draw upon to make new work. The UK does seem to be a place where rare-breed sheep and a more specialised fibre industry is thriving. I do feel that this commitment to utilising local materials and drawing upon history and tradition is very much transferable (and already happening) to other countries, e.g. Iceland. I see this as a positive and exciting trend in design and craft.

It’s very much an ethical choice: utilising what is around you. The calibre of the fibres from breeds of sheep in the UK is exceptional and I suppose the challenge is finding the right supply chain. The more that people know about the versatility of British wool, the higher the demand will be and the supply should follow the incline. There are fantastic mills in the UK spinning British wool, but there is definitely room for growth. On an aesthetic side there is also a wealth of possibilities for designs in only using British wool: whilst initially it can be restrictive and challenging opting to use one material source, ultimately, as a designer, it makes you more resourceful and challenges your practice and I feel stronger for it.

Once you restrict your palette, when you look a little closer, you realise there are many subtleties within it and a lot of scope for design.